< Historic Diamonds / Royal Stories

The Spanish Crown Jewels: Tracing Centuries of Royal Diamonds

From symbolic crowns to heirloom diamonds worn by generations of queens, explore the Spanish Crown Jewels and the legacy they continue to shape.

Published: January 16, 2026

Written by: Meredith Lepore

In Henry VI, William Shakespeare writes, “My crown is in my heart, not on my head; not decked with diamonds and Indian stones… my crown is called content.” This often-quoted line is striking not only because it was penned by one of the greatest literary minds of all time, but because, in just a few words, it captures a philosophy that closely mirrors the nature of the Spanish Crown Jewels: the crown itself is not worn by the monarch, but exists as a symbol of the monarchy, placed beside the throne during royal events such as proclamations, state occasions, and funerals.

That said, Shakespeare perhaps didn’t account for the fact that some of the Spanish Crown Jewels—though not the crown itself—are, in fact, richly adorned with extraordinary natural diamonds and gemstones.

Meet the Expert

Justin Daughters is the Director of Berganza, a UK-based antique and vintage jewelry dealer renowned for sourcing and presenting rare, museum-quality pieces. With a deep expertise in historic jewels, Daughters oversees a collection distinguished by exceptional provenance and authenticity.

Ahead is a detailed look at this extraordinary constellation of collections and the royals who wore them through centuries of political instability, exile, reinvention, and even dynastic conquest—including the seizure of jewels by Napoleon during the French occupation of Spain in the early 19th century.

Few royal jewelry legacies are as layered or enduring as this one, a history that continues today under the reign of King Felipe VI and Queen Letizia. These rare natural diamonds and gemstones have long served as symbols of empire, markers of dynastic continuity, and vessels of collective memory.

What Are the Spanish Crown Jewels?

The Spanish Crown Jewels are the symbolic regalia and historic diamond jewelry of Spain’s monarchy, including crowns, scepters, swords, and heirloom jewels that have been passed down through generations of royal families.

Their symbolism is just one of the many qualities that make the Spanish Crown Jewels so distinctive. Another is that they are not defined as a single, unified collection, as is the case with most royal lineages. Many monarchies possess a gem- or diamond-covered crown, a clearly delineated state jewel collection, and additional jewels housed in vaults or museums—often loaned out for major occasions (almost like a royal version of Blockbuster in the ’90s).

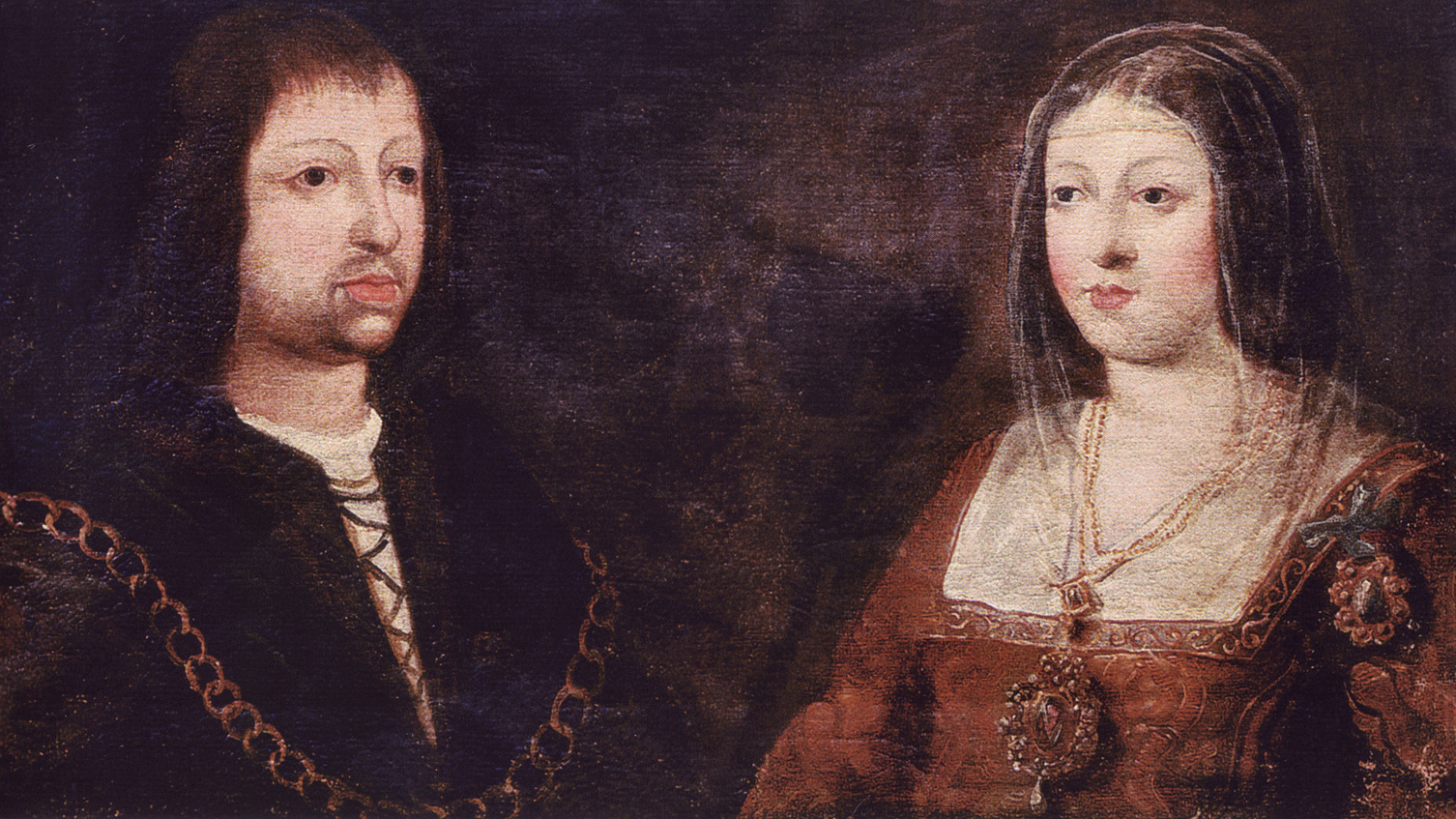

By contrast, the Spanish Royal Jewels comprise a combination of symbolic objects, such as scepters, swords, and crowns—alongside inherited personal jewels. These include exceptional wearable pieces set with natural diamonds, from tiaras and necklaces to brooches and earrings. Passed down through the centuries, the collection traces its origins to the late 15th century, beginning with the Catholic Monarchs, King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella.

The Origins of the Spanish Crown Jewels

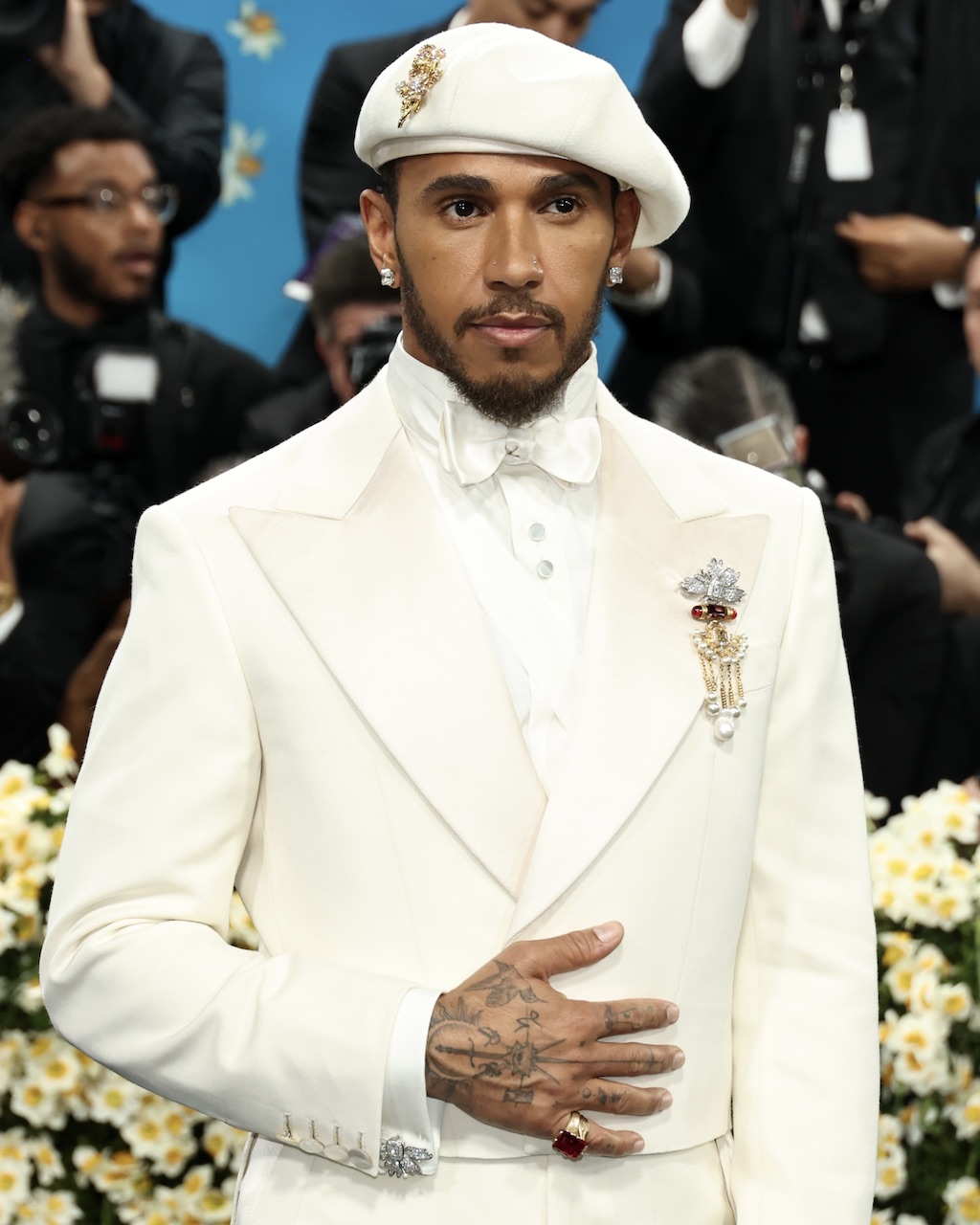

The Spanish Crown Jewels and Royal Collection developed in tandem with Spain’s rise as a global power. The marriage of Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile—both still teenagers at the time—unified Spain politically and spiritually, and jewelry played a meaningful role in signaling that union. Symbolic objects such as the Royal Scepter and Sword represented both sovereign authority and Catholic power, while the fine jewelry that followed reinforced the image of a divinely ordained, formidable monarchy rather than a frivolous one.

As Justin Daughters, Managing Director of Berganza, explains, “Spanish jewellery has always possessed a distinct ‘soul’ that separates it from the rest of Europe. During the Golden Age, we see a strong Baroque influence—deeply religious designs, often incorporating the joyas de pasar style, which favored large, high-quality gemstones over intricate metalwork.

He says, “There is a characteristic ‘Spanish drama’: sun-drenched gold, rich enamel work from Granada, and a preference for pearls and emeralds brought back from the Americas. The designs are often more architectural and ‘heavy’ than the delicate work found in the French or English courts, reflecting the stoic, religious, and formal nature of the Spanish Habsburg and early Bourbon courts.”

How the Spanish Crown Jewels Were Almost Stolen

Over the centuries that followed, the Spanish Crown Jewels and Royal Collection grew—and occasionally diminished—through inheritance, diplomatic exchange, strategic marriages, and conquest. One of the most consequential moments came at the outset of the Peninsular War in the early 19th century, when Napoleon invaded Spain. King Charles IV and his son Ferdinand VII were summoned to France, forced to abdicate the throne, and effectively held captive, while Napoleon installed his brother, Joseph Bonaparte, as King of Spain.

With the royal family displaced and invasion imminent, panic swept through the Royal Palace over how to protect its most valuable treasures. In a last-ditch effort, the Governor of the Palace ordered silk wall hangings removed from two rooms, creating cavities in the walls where jewels were hidden before being concealed again beneath embroidered silk. It was far from a foolproof plan—but it was the only option they had.

The French occupation proved short-lived. With resistance mounting inside Spain and British support strengthening the uprising, Joseph Bonaparte was forced to flee. He escaped with numerous stolen paintings and even the Royal Crown itself (which reportedly did not fit him), but the hidden jewels were never found. Years later, when Ferdinand VII returned to power, attempts were made to locate them, but the palace walls were never fully dismantled. Legend holds that some of those jewels remain hidden to this day.

Joyas de Pasar: The Heirlooms of the Spanish Crown Jewels

By 1906, when Queen Victoria Eugenia married King Alfonso XIII, the Spanish Royal Jewels began to take on a more cohesive identity. Their marriage ushered in an extraordinary influx of gifted jewels, including diamond tiaras, necklaces, and parures—many of which remain among the most important pieces in Spain’s royal jewelry history. Take that, Napoleon.

What distinguishes these jewels is their remarkable consistency: exceptional, high-quality diamonds, a restrained use of colored gemstones, and a strong emphasis on symmetry, clarity, and proportion. Crafted predominantly in platinum and other white metals—a hallmark of early 20th-century jewelry design—these pieces reflect a modern, refined elegance rather than ostentation. Many were designed with versatility in mind, able to transform from tiaras into necklaces or from brooches into multi-strand adornments.

This group of jewels would later become known as Joyas de Pasar, a term coined by María de las Mercedes of Bourbon-Two Sicilies, the wife of Don Juan, Count of Barcelona, and grandmother of King Felipe VI. The phrase—loosely translating to “jewels to pass on”—reflects their unique status: not state-owned crown jewels, but privately held royal treasures meant to be inherited from queen to queen.

Often reserved for the most solemn and significant occasions, Queen Victoria Eugenia ensured that the jewels she received at and after her 1906 wedding would form a continuous royal lineage. Passed discreetly through generations, the Joyas de Pasar remain one of the most distinctive and emotionally resonant traditions in European royal jewelry.

The Most Notable Jewels in the Spanish Crown Jewels Collection

The earliest Spanish royal jewels were not defined by an abundance of diamonds, but over time, extraordinary stones entered the collection in meaningful waves. What makes the Spanish Royal Jewels particularly distinctive is their evolving functionality. Under the influence of Queen Victoria Eugenia in the early 20th century, many pieces were reworked, reconfigured, and worn in multiple ways across generations, often acquiring new symbolism with each decade.

The Royal Crown of Spain (Corona Tumular) and Royal Sceptre

The Royal Crown of Spain, also known as the Corona Tumular, is one of the most unusual crowns in Europe. Crafted from gold-plated silver and entirely devoid of gemstones, it is decorated instead with heraldic symbols—a turret and a lion—representing the historic kingdoms of Castile and León. The crown was commissioned around 1775 by King Carlos III and was intended as a symbolic object rather than a wearable crown.

True to its purpose, the Corona Tumular has never been worn. Instead, it is displayed beside the throne during major state occasions to represent the authority and continuity of the Spanish monarchy. Most recently, it was used during the proclamation of King Felipe VI in 2014.

The Royal Sceptre predates the crown by centuries. It was gifted to King Felipe II in the 16th century by Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Bohemia. Like the crown, the sceptre functions as a symbol of sovereignty rather than a personal adornment.

Today, both the Royal Crown and Sceptre are on permanent public display in the Crown Room at the Royal Palace of Madrid, reinforcing one of the defining principles of the Spanish Crown Jewels: power is represented, not worn.

The Diamond Chaton Necklace (Collar de Chatones)

Now we can get to the stunning natural diamonds of the Spanish Crown Jewels and royal collection, beginning with one of the most important pieces in the Spanish royal jewelry canon, the Diamond Chaton Necklace (also known as the Collar de Chatones). A wedding gift from King Alfonso XIII to Queen Victoria Eugenia, the necklace was worn by the bride on her wedding day in 1906. At the time, it comprised 30 large, round-cut diamonds set as individual collets.

In what may be one of royal history’s most enduringly practical romantic gestures, Alfonso XIII continued to gift his wife additional diamond collets for major milestones—birthdays, anniversaries, and the births of their children (an early—and exceptionally glittering—version of the push present). Over time, the necklace grew both longer and heavier, eventually prompting Queen Victoria Eugenia to divide it into two separate strands: one composed of 38 collets and a shorter chain of 27. She frequently wore them together, separately, or styled as a sautoir, depending on the occasion.

With this marriage, Queen Victoria Eugenia ushered in a new and transformative era for the Spanish Royal Jewels, bringing with her not only diamonds but an entirely new aesthetic sensibility.

Daughters says, “Queen Victoria Eugenie, known as Queen Ena, was a transformative figure for Spanish style. Born a granddaughter of Queen Victoria at Balmoral, she brought the more ‘airy’ and ‘modern’ aesthetics of London and Paris to Madrid.” He noted that the best illustration of her style is the Diamond Chaton Necklace. “At the time, this shift was seen as a breath of fresh air; it moved away from the rigid, fixed settings of the past towards the more fluid, versatile jewellery that defined the early 20th-century European elite.”

The Cartier Diamond and Pearl Tiara

Queen Victoria Eugenia’s mother-in-law, Maria Christina of Austria, was famously unenthusiastic about her son’s choice of bride. Having hoped Alfonso XIII would marry a higher-ranking, born-Catholic princess, the Queen Mother was reportedly restrained when it came to wedding gifts. What she did commission, however, was a striking, Louis XVI–inspired diamond and pearl tiara created by Spain’s official court jeweler, Ansorena—an imposing piece defined by its height and formal symmetry.

Queen Ena appears to have had little affection for the tiara in its original form. While it is sometimes associated with her wedding trousseau, clear photographs of her wearing it as originally designed are notably scarce, suggesting it never became a favored piece in her personal rotation.

After becoming Queen, Ena brought the tiara to her preferred jeweler, Cartier, where it was substantially reworked to better suit her taste and the emerging style of the period. The redesigned version took on a lighter, Edwardian character, emphasizing diamond garland and foliate motifs set in platinum and centered with prominent pearls. This softer, more fluid iteration proved far more to her liking, and she was photographed wearing the remodeled tiara on multiple occasions throughout the 1920s.

“Queen Ena was a devoted patron of Cartier, and this relationship fundamentally changed the ‘silhouette’ of the Spanish monarchy. Cartier introduced the ‘Garland Style’ and later Art Deco influences to the court,” says Daughters.

Ena didn’t stop there. Elements associated with the tiara were further adapted into diamond bracelets, reinforcing her preference for jewels that could evolve and be worn in multiple ways rather than remain fixed in a single form.

“These pieces utilised platinum, a metal that allowed for incredibly fine, almost invisible settings. This made the jewellery look like it was floating on the hair or skin, a stark contrast to the heavy gold and silver frames of previous Spanish tiaras. Cartier’s influence brought a sense of ‘International Chic’ to Madrid, ensuring that the Spanish court looked as modern as those in London or Paris,” says Daughters.

The Cartier Diamond and Pearl Loop Tiara

Often referred to simply as the Cartier Loop Tiara, the Cartier Diamond and Pearl Loop Tiara is among the most understatedly elegant jewels in the Spanish royal collection. Created by Cartier in the late 19th or early 20th century and traditionally associated with Maria Christina of Austria, the tiara is defined by a rhythm of diamond looped garlands, each softly accented with small pearls.

Executed in platinum, the design feels light and architectural, its symmetry signaling a shift away from the heavier, pearl-forward tiaras of the previous century toward a more modern, international sensibility. Worn throughout the 20th century by Queen Sofía and, more recently, by Queen Letizia, the tiara embodies a defining principle of the Spanish Crown Jewels: refinement over excess, and jewels meant to endure through wear rather than spectacle.

The Fleur-de-Lis Tiara

Queen Victoria Eugenia was famously fond of tiaras—and in addition to her diamond and pearl wedding tiara, her husband, King Alfonso XIII, presented her with what would become the most important tiara in the Spanish royal collection: the Fleur-de-Lis Tiara. Gifted on their wedding day in 1906, Queen Ena wore the tiara for the ceremony itself, perching it atop her already impressively high bouffant—a look that proved undeniably regal.

The Fleur-de-Lis Tiara was also worn in the couple’s first official portraits as husband and wife, cementing its place in Spanish royal history from the very beginning.

“The Fleur-de-Lis Tiara, known affectionately in the family as ‘La Buena’ (The Good One), is perhaps the most iconic piece in the Spanish collection. Created by the Spanish jeweller Ansorena in 1906, it features three massive fleurs-de-lis [filled with large diamonds]. The motif is deeply dynastic: the fleur-de-lis is the heraldic emblem of the House of Bourbon,” Daughters says.

By wearing it, the Queen is quite literally wearing the family’s coat of arms. It symbolises the restoration and the permanence of the Bourbon line in Spain. Today, it is part of the Joyas de Pasar, the ‘Jewels that are passed’, reserved exclusively for the Queen herself on the most solemn state occasions, acting as a crown in all but name.”

Like many jewels within the Joyas de Pasar, the Fleur-de-Lis Tiara was designed with versatility in mind and can also be worn as a dramatic corsage brooch—reinforcing the uniquely Spanish tradition of heirloom jewels that adapt across generations while retaining their symbolic power.

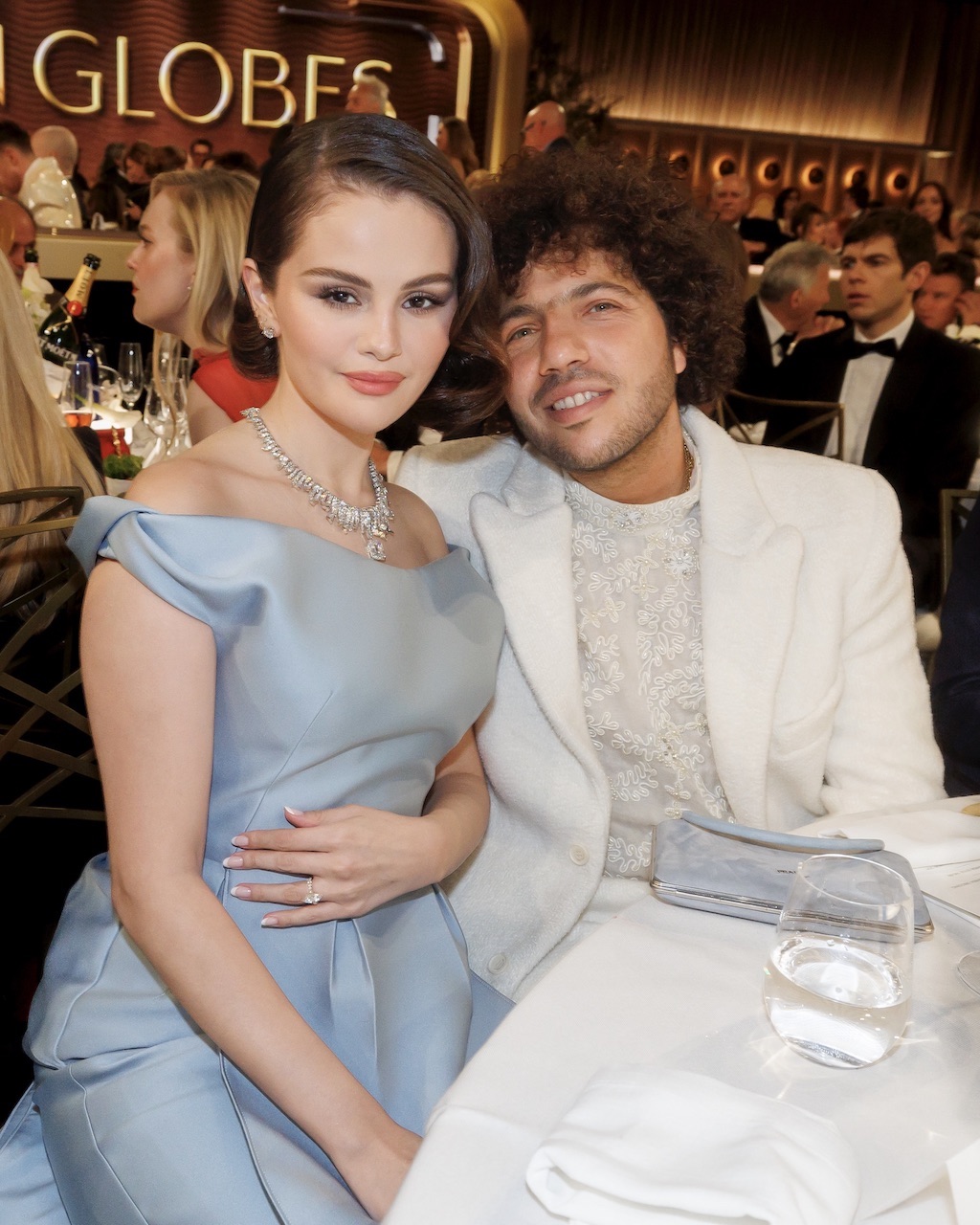

La Peregrina Pearl (And How Elizabeth Taylor Almost Lost It)

It may not be a diamond, but it is arguably the most famous pearl in human history. According to Daughters, the 500-year journey of this extraordinary gem began in the Gulf of Panama in 1513, where it was discovered by an enslaved diver who was reportedly granted his freedom in exchange for the pearl. The naturally ear-shaped pearl—measuring approximately 55.95 carats—was sent to Philip II of Spain, who later gave it to Mary I of England as a wedding gift.

Following Mary’s death, the pearl returned to Spain, where it was worn by generations of queens and immortalized in portraits by Diego Velázquez. It later disappeared during the Napoleonic Wars, when it was taken by Joseph Bonaparte—earning the pearl its enduring nickname, La Peregrina, or “the Wanderer.”

Centuries later, La Peregrina entered a new chapter of its storied life when it came into the possession of none other than Elizabeth Taylor. Despite her legendary love of diamonds, Taylor was deeply devoted to pearls. In 1969, while staying at Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas, she realized the pearl was missing and feared it had been lost forever. After searching the hotel room in mounting panic, she noticed one of her Pekingese puppies chewing on something small. Inside the dog’s mouth was La Peregrina—miraculously unharmed.

Taylor later recounted the incident in her memoir, Elizabeth Taylor: My Love Affair with Jewelry, describing both the terror of losing the historic pearl and the overwhelming relief of recovering it intact.

Remarkably, this was not the first time La Peregrina had gone missing. Despite its substantial size—measuring approximately 17.35–17.90 x 25.50 mm—it was reportedly once lost in couch cushions at both Windsor Castle and Buckingham Palace before being safely recovered. Royals, it seems, really are just like us—except when they misplace history’s most priceless pearl instead of a popcorn kernel.

Later, Taylor commissioned Cartier to set La Peregrina into a ruby and diamond necklace, with the pearl suspended low in a design likely inspired by Velázquez’s portraits of Spain’s Queen Margarita and Queen Isabel, who had also worn the pearl as a pendant. The necklace was auctioned by Christie’s in 2011, where it sold for $11 million.

Daughters says of La Peregrina, “Its icon status comes from this 500-year thread of survival, connecting the conquest of the Americas to the height of Hollywood royalty. It is a tangible link between the age of explorers and the age of modern celebrity.”

Though the pearl is undeniably the star, La Peregrina has long been paired with diamonds to dramatic effect. From the 16th century onward, queens of Spain—including Isabel de Borbón and Mariana of Austria—wore it suspended from pearl strands or as a diamond brooch pendant. Queen Isabel II favored the same styling, and most recently, Queen Letizia wore La Peregrina in 2017 as a diamond brooch pendant attached to a pearl necklace, a modern nod to one of the most extraordinary jewels ever worn.

The Diamond Solitaire Earrings

The 10-carat round-cut Diamond Solitaire Earrings were another exceptional wedding gift from King Alfonso XIII to Queen Victoria Eugenia. Worn on her wedding day in 1906, the earrings quickly became signature pieces—appearing in official portraits throughout her reign and continuing to be worn even after the royal family went into exile.

Like many of Queen Ena’s jewels, the earrings evolved with changing fashions. In the 1920s, the two diamonds were reimagined in a more Art Deco style and made adjustable, allowing them to be worn in multiple configurations. Photographs from the period frequently show her wearing them alongside her Cartier diamond tiara.

In the 1930s, the earrings were updated again into button-style earrings, each solitaire surrounded by twelve smaller round diamonds. This redesign coincided with the family’s exile following the fall of King Alfonso XIII’s monarchy in 1931, after republican victories in municipal elections prompted the royal family to leave Spain to avoid civil war.

Queen Ena wore the diamonds in all their iterations throughout her life and was frequently photographed in them at significant events, including royal weddings. She even wore them for an official Life magazine photo shoot in the 1950s at her home in Switzerland. Among the most memorable images are those of Ena wearing the earrings alongside her close friend Grace Kelly—to whose son, Prince Albert II, she was godmother.

The Prussian Tiara

The Spanish royals’ love of diamond tiaras extended well beyond their own borders, and the Prussian Tiara is a perfect example. Created in the early 20th century by German court jeweler Koch, the tiara was originally made for Princess Viktoria Luise of Prussia and worn for major court occasions, including a highly publicized visit to Buckingham Palace in 1911.

Designed in a neoclassical style, the tiara is set with diamonds and 27 pearls, many of them pear-shaped drops. Its defining silhouette is influenced by the Russian kokoshnik—an arched form characterized by vertical elements (here, diamond-set columns) rising from a symmetrical base.

The tiara passed through several royal hands, including Princess Friederike of Hanover, and later to her granddaughter Queen Sofía, both of whom wore it on their wedding days.

Today, Queen Letizia frequently wears the Prussian Tiara for formal state dinners. Unlike some of the more monumental pieces in the Spanish collection, its refined scale makes it surprisingly wearable—proof that not every royal tiara needs to be overwhelming to make a statement.

The Spanish Crown Jewels as Living History

The Spanish Royal Jewels have lived many lives. They have survived wars, palace seizures, exile, and even—briefly—the inside of Elizabeth Taylor’s dog’s mouth. These are not objects locked away in vaults, but jewels that have been worn, adapted, and reinterpreted across centuries (with the notable exception of the symbolic crown, which carries its power through presence rather than use).

Together, they form a living archive—jewels that tell a story of empire, faith, lineage, loss, and resilience. The Spanish Crown Jewels are not just historical artifacts; they are vessels of cultural memory, preserved not by stillness but by continued life.