< Historic Diamonds / Royal Stories

Jacqueline de Ribes and the Art of Wearing Natural Diamonds

From a historic diamond tiara she daringly dismantled to sculptural statement necklaces worn with striking precision, discover how Jacqueline de Ribes transformed natural diamonds into living fashion.

Published: February 19, 2026

Written by: Meredith Lepore

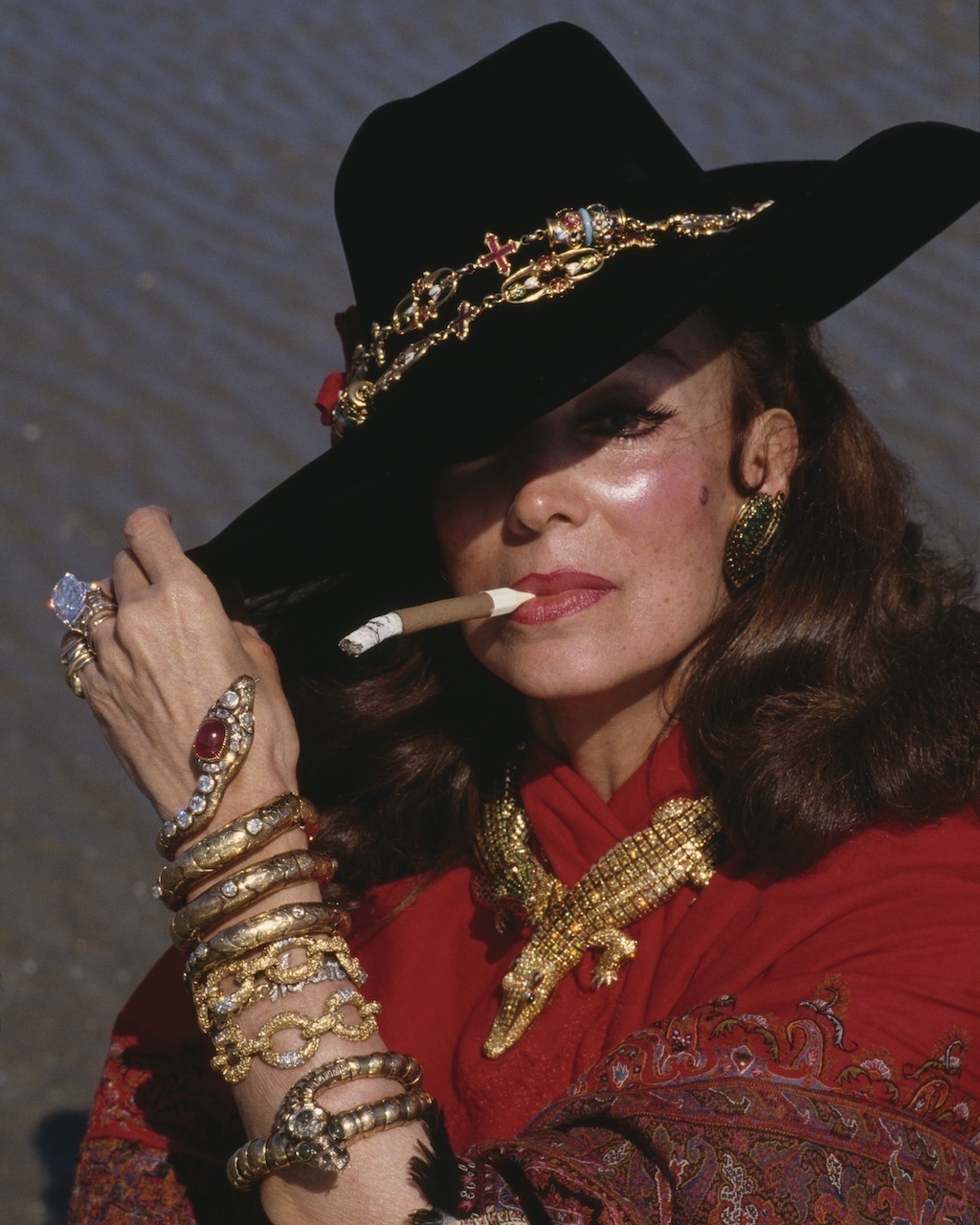

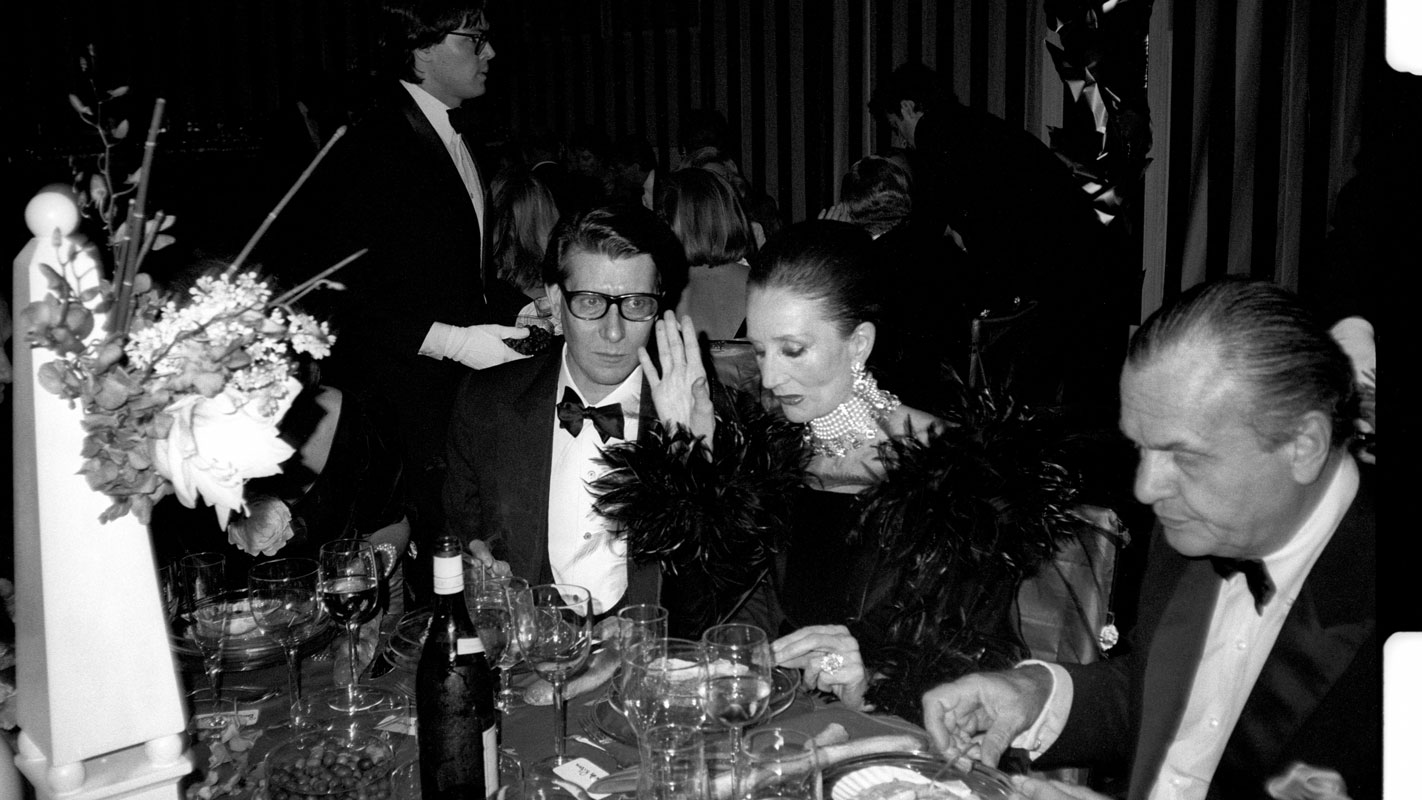

The great Yves Saint Laurent once said of Jacqueline de Ribes, “She is a beacon, she radiates, her long neck gleaming with the brilliance of a thousand lights. Lyre-bird. Kingbird. Bird of Paradise.” Whether or not she was wearing a diamond necklace on her renowned neck is unclear, but we wouldn’t be surprised if this icon of style and class was draped in stunning jewels when the designer spoke these words.

Ribes, who passed away at the end of 2025, should not be dismissed as merely a socialite. She was an accomplished designer, collector, patron of the arts—and someone who understood the power of jewelry as a form of authorship. Considered one of the most stylish women in the world for decades, she was counted among Truman Capote’s Swans, bestowed the title “the last Queen of Paris,” and famously cited as the muse Joan Collins was encouraged to channel for her iconic role in Dynasty. In 2015, she was the subject of a major exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Jacqueline de Ribes: The Art of Style, a tribute to her extraordinary and enduring influence.

Diamond jewelry was, of course, part of what made her style, but her unique approach truly set her apart from her contemporaries. Justin Daughters, Managing Director of Berganza, told Only Natural Diamonds, “For Jacqueline de Ribes, jewellery was never a finished product; it was a set of components.”

Meet the Experts

Justin Daughters is the Director of Berganza, a UK-based antique and vintage jewelry dealer renowned for sourcing and presenting rare, museum-quality pieces. With a deep expertise in historic jewels, Daughters oversees a collection distinguished by exceptional provenance and authenticity.

Amélie Huynh is the founder the jewelry Maison STATEMENT, founded in 2018. Huynh honed her craft at one of the most prestigious houses on Place Vendôme, her creations reveal a deep connection between precious materials and pure emotion.

Considered by some as one of the most important but unofficial jewelry stylists of the 20th century, Jacqueline de Ribes didn’t simply wear glamorous jewelry; she reinterpreted it.

The Aristocrat Who Designed Her Own Image

Born in 1929 in Paris, Jacqueline Bonnin de La Bonninière de Beaumont came from an aristocratic family. Her grandfather founded the French Rivaud bank, and her father, Jean de Beaumont, Comte de Beaumont, was a Commander of the Legion of Honor and a member of the International Olympic Committee. His wife, Paule de Rivaud de La Raffinière, might have competed for Mother of the Year with Joan Collins—albeit with old money and a French accent. De Ribes often described her childhood as unhappy and her mother as distant and cruel..

She discovered her love of clothing by poring over her grandmother’s haute couture collection in the family château. Meeting designer Christian Dior at the impressionable age of 16 further ignited what would become a lifelong devotion to couture.

In 1948, at just 18 years old, she married Vicomte Édouard de Ribes, a banker from another prominent society family who later became Comte de Ribes and an Officer of the Legion of Honour. The couple had two children.

Now known as Vicomtesse Jacqueline de Ribes, she assembled the perfect society wardrobe for costume balls, charity soirées, and glittering benefits, all while living in a grand hôtel particulier in Paris. Yves Saint Laurent, Cristóbal Balenciaga, and Hubert de Givenchy became among her most trusted designers. In turn, she served as a breathtaking muse to them all.

De Ribes developed the fancy habit of cutting up her couture gowns and reworking them into entirely new creations—experimenting with altered waistlines, unexpected proportions, and fresh silhouettes. The press took notice, and by the 1950s, she was designing her own dresses, commissioning a then-unknown Oleg Cassini to execute her custom gowns. Another early collaborator? None other than a young Valentino, whom she hired to assist with her sketches.

In 1983, she launched her own ready-to-wear collection, attracting a devoted clientele that included fashion icons such as Joan Collins, Raquel Welch, author Danielle Steel, and members of the Rothschild family. By 1995, despite the brand generating more than $3 million annually, she retired for health reasons.

Jacqueline de Ribes’ Jewelry Philosophy

Jacqueline de Ribes viewed jewelry—especially diamond pieces—in much the same way she approached clothing: as raw material to be shaped, reimagined, and composed into something entirely her own. From a young age, she understood proportion instinctively, recognizing how a jewel could transform a silhouette and accentuate the body as powerfully as any gown. Her eye for jewelry was nothing short of extraordinary.

Here’s where those instincts came into play, and the radical natural diamond philosophy that helped cement her iconic status.

The Diamond Fleur-de-Lys Tiara

Jacqueline de Ribes is perhaps best known for her Diamond Fleur-de-Lys Tiara—and for what she chose to do with it. Though the maker of the diadem is unknown, it is believed to have originated in the collection of Wilhelmina, Lady Dalmeny, who later became the Duchess of Cleveland. Upon her death in 1891, the tiara passed to her daughter before eventually reappearing on the market. De Ribes acquired it shortly after it was sold at Christie’s in the mid-1970s.

The stunning tiara consists of pear-shaped pearls and diamond fleur-de-lys motifs arranged on an intricate diamond base. “The fleur-de-lys has long symbolised nobility, purity and continuity. Its association with the French monarchy imbues it with authority, while its floral form introduces softness and femininity… When combined with pear-shaped pearls… the symbolism becomes layered: strength balanced by grace. The inclusion of Celtic knots introduces the idea of eternity and interconnectedness,” says Daughters.

While it never formed part of a reigning royal treasury, its fleur-de-lys motifs situate it within the same visual tradition as the great European court tiaras that still reside in royal collections today.

Amélie Huynh, Founder and Designer at STATEMENT Paris, tells Only Natural Diamonds, that the motif of the fleur-de-lys suggests continuity and eternity — an unbroken lineage. She also notes, “The motif aligned naturally with her aristocratic background, but even more with her commanding personality… In her case, the fleur-de-lys did not feel theatrical; it felt earned.”

It was precisely this interplay of symbolism and structure that made the Diamond Fleur-de-Lys Tiara such a natural extension of de Ribes’ aesthetic. Daughters adds that as a celebrated tastemaker, de Ribes was drawn to drama and strong lines. “The fleur-de-lys is a graphic, vertical motif that complemented her famous ‘Nefertiti’ profile and long neck… noble enough to honour her heritage, but bold enough to satisfy her ‘quite crazy or terribly strict’ fashion philosophy.”

Reimaging the Diamond Fleur-de-LysTiara

For most women, a tiara of this caliber would be reserved for ceremonial occasions and worn intact upon the head. For de Ribes, however, it offered endless possibilities. The natural diamonds became compositional elements: she detached sections and wore them as brooches or shoulder ornaments. Why confine a tiara to the crown when it could be reimagined?

The very fact that these natural diamonds had already lived full aristocratic lives before she encountered them made her gesture even more radical. De Ribes was not dismantling costume jewelry; she was reinterpreting history.

She often paired the transformed pieces not with elaborate ball gowns, but with pared-back black dresses that allowed the diamonds to command attention. “By breaking a tiara into brooches, she demonstrated a modular, dynamic understanding of luxury. She refused to let the ‘intended use’ of a piece dictate her style. This approach reveals a woman who viewed jewelry as architecture for the body,” Daughters says.

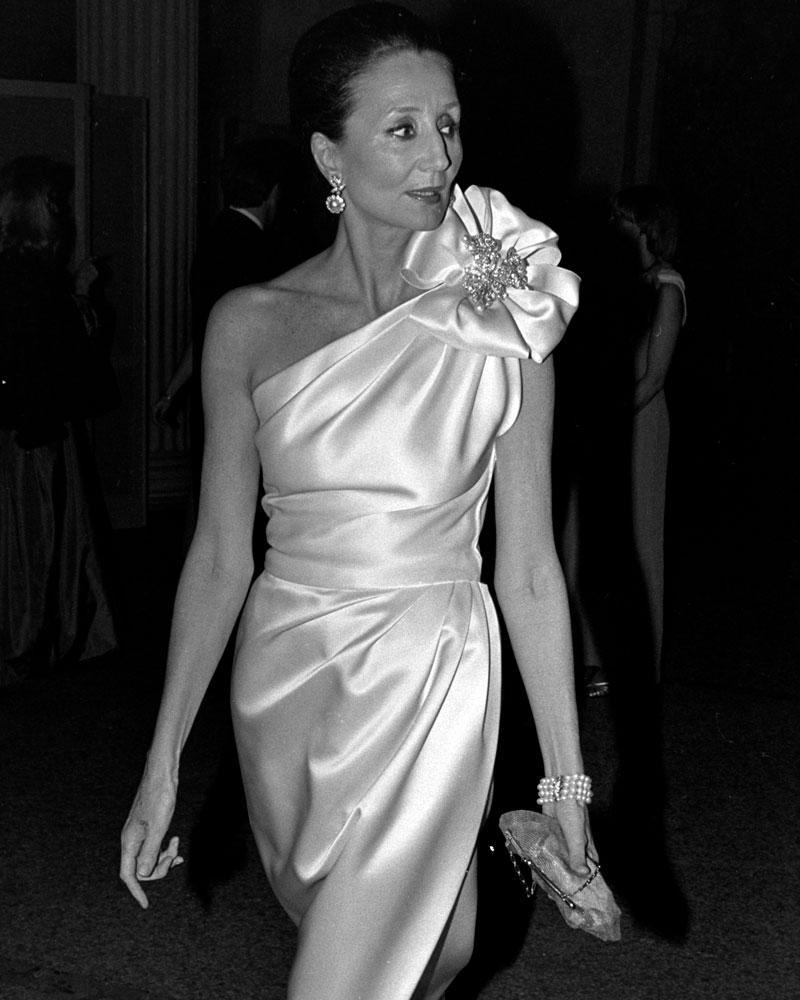

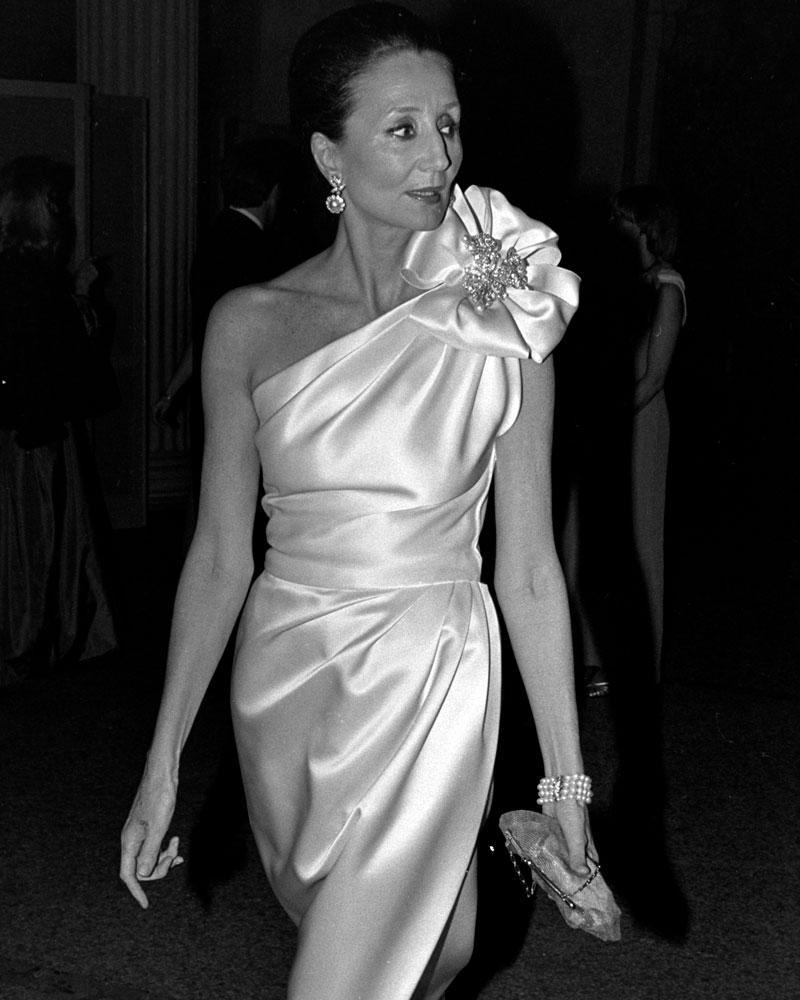

She wore the piece in its traditional form at the 1973 Wedding Ball of the Count of Quintanilla and Princess Teresa zu Sayn-Wittgenstein-Sayn. By 1976, she had reworked it into a brooch clasping her gown at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The following year, at Le Grand Hôtel in Paris, she combined all three diamond fleur-de-lys elements into a dramatic, oversized brooch. She continued to style it this way at several high-profile events, including a 1979 party at the Met, a Tiffany & Co. fête at the St. Regis the following year, and the 1984 centennial gala of the Metropolitan Opera, where the three brooches adorned the neckline of a pale pink gown.

Huynh explains that dismantling the tiara reveals de Ribes philosophy on jewelry: even when museum-worthy, it is meant to live. “She reinterpreted a formal, almost ceremonial object into something modern, personal, and wearable. It speaks to her understanding of jewelry as dynamic — not fixed in form, but adaptable to the woman who wears it,” she says. “The tiara could accompany her silhouettes, enhance her dramatic gestures, and integrate seamlessly into her avant-garde style — without appearing costume-like or excessively formal. In doing so, she transformed inherited symbolism into self-expression. The object no longer dictated the occasion; she did.”

Daughters echoes this sentiment and notes that de Ribes demonstrated a “modular, dynamic understanding of luxury.” She refused to let the “intended use” of a piece dictate her style, viewing jewelry instead as architecture for the body. A tiara, traditionally a marker of ceremony and status, became in her hands an avant-garde accessory. As Daughters puts it, the narrative shifted from “I am a Countess” to “I am a designer of my own image.”

Diamonds as Architecture for the Body

Though she was photographed countless times in striking statement necklaces, the exact makers of many of these pieces remain undocumented. She favored diamonds, gold, sculptural forms, and linear rivière designs that hugged the collarbone. What unified nearly every necklace she wore was not its size, but the geometry it created against her frame. Like the Diamond Fleur-de-Lys Tiara, she would often wear these beautiful pieces with stark black gowns, allowing the jewelry to command full attention. She rarely, if ever, layered necklaces. It was a restraint that reinforced her architectural precision.

Time and again, she returned to natural diamonds—not merely for their brilliance, but for their permanence. You see the same thing with her choice of diamond earrings. They were not static pieces but were activated by the turn of her head and the rhythm of light, making them a photographer’s dream (Richard Avedon frequently snapped her). De Ribes understood how to position herself to accentuate her jewels, a sense of theatricality perhaps sharpened by her later involvement with the Grand Ballet du Marquis de Cuevas.

How Jacqueline de Ribes Rewrote the Rules of Modern Luxury

As Huynh observes, when confronted with a piece of such immense historical magnitude, the instinct might be to secure it and lock it away, but de Ribes rejected that notion. “For her, the tiara was not a static artifact; it was an active extension of her identity. By dismantling and reimagining it, she demonstrated that luxury is not defined solely by preciousness or tradition. True luxury lies in authorship — in the confidence to reinterpret history rather than simply preserve it. The tiara remained precious, but it ceased to be traditional. It moved from museum object to living fashion statement — and in doing so, became even more powerful.”

As we saw with that extraordinary tiara, de Ribes gave it a second life. She transformed it and made it contemporary. For her, natural diamonds were not static relics, but living instruments of self-expression. And that may be the most modern way to wear diamonds of all.