< Historic Diamonds / Famous Diamonds

The Diamonds of Doris Duke: The Last Gilded Age Socialite

From inherited Cartier masterpieces to boldly reset diamonds, explore the jewels that reflected Doris Duke’s unconventional life and enduring legacy.

Published: January 20, 2026

Written by: Meredith Lepore

When you are labeled the “richest little girl in the world” at the age of 12, an extraordinary—and inevitably complex—life awaits. When Doris Duke became the sole heir to her father, American Tobacco Co. magnate James Buchanan Duke, in 1925, she inherited an estimated $100 million fortune, along with vast properties including Duke Farms in New Jersey, Rough Point in Newport, and a mansion in New York City. That fortune would shape every facet of Duke’s life—from philanthropy and travel to art, architecture, and, perhaps most surprisingly, jewelry.

Duke’s wealth was so immense that when she married for the second time in 1947, to Porfirio Rubirosa, the U.S. State Department required her to sign a prenuptial agreement to ensure her money would not be used for political purposes.

Meet the Experts

Zuleika Gerrish is an antique, vintage and fine jewelry expert as well as a gemmologist and co-founder of Parkin and Gerrish with her husband Oliver. She is a qualified FGA (Fellow of the Gemmological Association) and DGA (Diamond Member), and is training to become an IRV (Institute Registered Valuer) through the National Association of Jewellers.

Justin Daughters is the Director of Berganza, a UK-based antique and vintage jewelry dealer renowned for sourcing and presenting rare, museum-quality pieces. With a deep expertise in historic jewels, Daughters oversees a collection distinguished by exceptional provenance and authenticity.

Though she would later insist her jewelry collection was “entirely accidental,” it ultimately became one of the most important private collections of the 20th century. Ahead, we explore how Doris Duke’s singular life, taste, and independence shaped the extraordinary natural diamond jewelry she chose—piece by piece.

Doris Duke: Heiress, Adventurer, Philanthropist

Doris Duke was not a pampered socialite content to live quietly behind gilded doors. Her second marriage would be her last, though her personal life was often the subject of fascination, with rumored romances spanning Hollywood, sports, music, and even the military—proof that Doris Duke certainly didn’t have a type. Yes, she had all the money one could ever desire, but she used it not merely to acquire things, but to experience life fully.

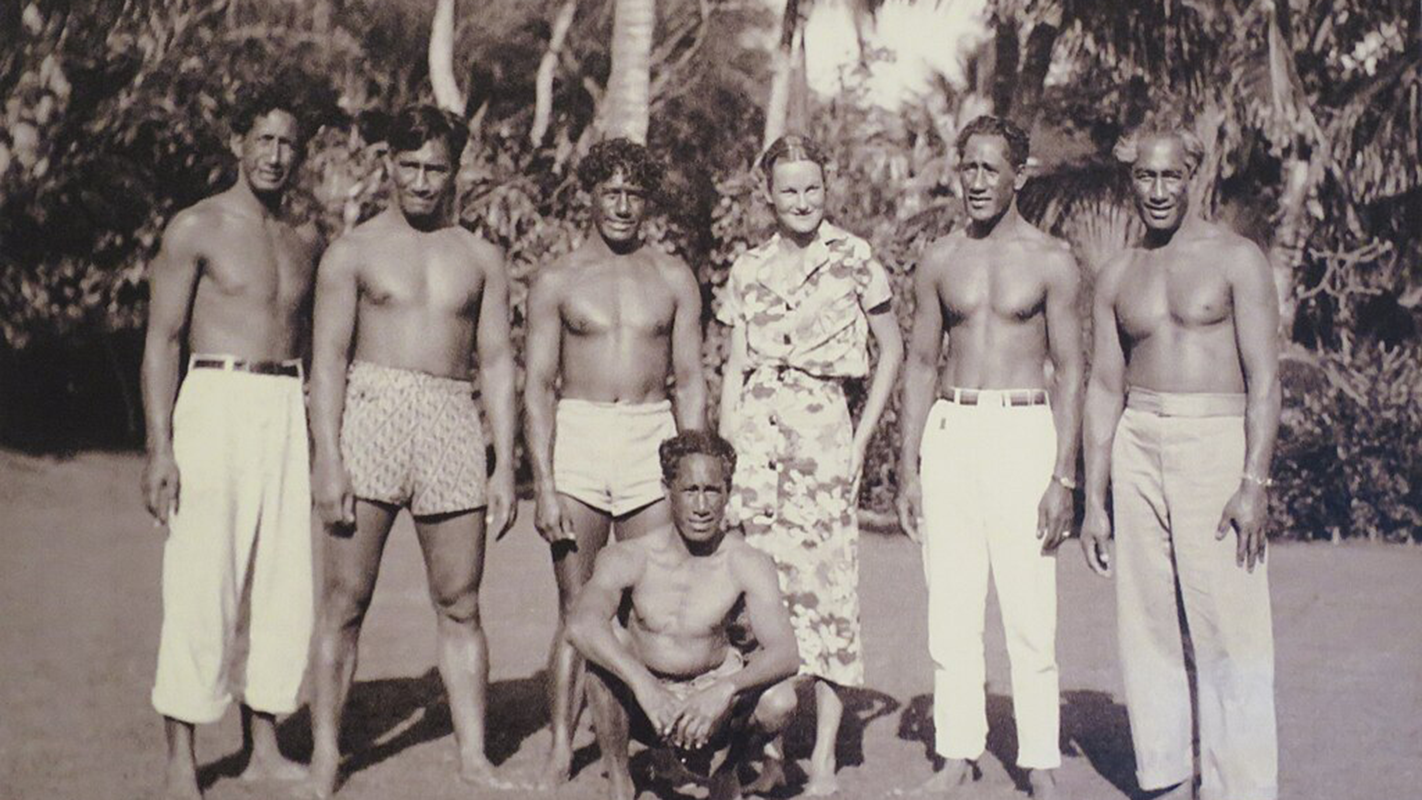

She served as a war correspondent and contributor for Harper’s Bazaar, became a competitive surfer in Hawaii (a rarity for women at the time), assembled an extraordinary collection of Islamic art, traveled the world—famously purchasing her own Boeing 737—kept two pet camels in Newport, and emerged as one of the most influential philanthropists of the 20th century.

Following in her father’s footsteps—he left half of his fortune to charity upon his death and established the Duke Endowment in 1924, including a substantial gift to create Duke University as a memorial to his father—she went on to establish one of the country’s largest philanthropic organizations, the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, and donated more than $400 million throughout her lifetime, including $1 million to her friend Elizabeth Taylor’s AIDS Foundation.

Though she never considered herself a jewelry collector, she nonetheless assembled a remarkable collection. Many of the pieces were inherited from her mother, Nanaline Holt Inman Duke, who died in 1962. Her mother provided a solid foundation for the collection, including rare Belle Époque Cartier pieces as well as the famous Cartier Art Deco Bandeau Tiara. But Duke’s extensive wanderlust, which took her to India and Southeast Asia, also led her to acquire highly distinctive and beautiful pieces along the way. She developed a strong relationship with Cartier over her lifetime and, in the later decades of her life, also acquired pieces by Tiffany & Co. and David Webb.

“Doris Duke was one of the most significant American jewelry collectors of the 20th century, not because she bought the most diamonds, but because she understood top quality. Her extraordinary fortune came to over more than $100 million (over $1.4 billion today), giving her unrivalled purchasing power – even during the Depression. But wealth alone does not explain her importance as a collector,” says Zuleika Gerrish, Co-Founder of Parkin and Gerrish and a fine jewelry expert.

How Doris Duke Built Her Diamond Collection

Duke’s collection was renowned for its elegant amalgamation of inherited treasures, commissioned works, and exceptional Art Deco and Belle Époque designs. Early exposure to jewelry through her mother, combined with extensive travel, shaped her lifelong fascination with diamonds and fine luxury pieces.

Justin Daughters, Director of Berganza, tells Only Natural Diamonds, “How Doris Duke collected diamonds reflects a collector driven by curiosity and personal conviction rather than status alone. Many twentieth-century collectors chased size or spectacle, while Duke focused on character, provenance, and design integrity. Diamonds served as anchors rather than statements of excess. Choices leaned towards refined cuts, balanced proportions, and historic houses such as Cartier. This approach placed her closer to a connoisseur than a social showpiece wearer. Taste evolved across decades, yet consistency remained through restraint and intellectual engagement with jewellery as a cultural object.”

The Duke collection was a perfect blend of inherited heirlooms and personal creativity manifested in diamonds. “The blend of inherited jewels and personal intervention defines much of the collection’s identity. Heirlooms such as the Cartier Art Deco bandeau tiara carried established social meaning and lineage. Duke treated such pieces as living objects rather than fixed relics. Stones moved. Mounts changed. Diamonds passed through multiple chapters of use. This practice reflects confidence and independence. Rather than preserving jewels as untouched symbols of inheritance, Duke reshaped meaning through wear and reinterpretation. Creativity existed alongside respect for origin,” he says.

How Travel Influenced Doris Duke’s Diamond Collection

Travel was part of Duke’s DNA. She began traveling abroad as an infant, but perhaps the most influential journey of her life—and the one that sparked her enduring love of Islamic art and jewels—was her 1935 honeymoon with her first husband, James Cromwell. The couple traveled through Egypt, India, Iran, Morocco, Spain, Syria, Uzbekistan, and Turkey. That trip marked the beginning of Duke’s collection of textiles, ceramics, architectural elements, and jewelry from across the Islamic world.

The journey also inspired her to build Shangri La, a five-acre estate overlooking the Pacific Ocean in Honolulu, Hawaii. Construction began in the mid-1930s and continued to evolve over the next 50 years. Much like her jewelry collection, the estate’s art and architecture span a wide range of periods—from pre-Islamic and medieval eras to the mid-20th century—and incorporate diverse materials, styles, and techniques from across the Islamic world.

Daughters says, “Travel played a decisive role in shaping aesthetic direction. Extended exposure to Asia and India introduced scale, colour contrast and symbolic layering. Diamond settings often appeared alongside pearls, colored gemstones, or carved elements drawn from non-Western traditions. Such combinations created dialogue between European diamond tradition and global ornament. Influence surfaced through balance rather than imitation. Diamonds retained central presence while surrounding materials expanded narrative depth.”

Duke’s travels were not just formative experiences; they became a visual language that shaped her collecting instincts. Gerrish reiterated this connection, explaining:

“Her serious engagement with Islamic, Indian, and Middle Eastern art, later formalised through the Shangri La and the Doris Duke Foundation for Islamic Art, found its way into her jewelry. The architectural clarity and geometric discipline admired in these traditions recur in her diamond pieces, particularly those produced by Cartier New York, where Indian and Islamic motifs were consciously translated into modern form.”

Doris Duke’s Relationship with Cartier

Cartier was a part of Duke’s life from the beginning, as her mother was an avid collector. After her mother’s death, Duke would continue the relationship, commissioning and often resetting pieces just as her mother had.

“Duke was a key client for Cartier, particularly in the 1930s, when very few Americans (and Europeans) could still afford fine diamond jewellery. Contemporary Cartier records describe her as ‘very exacting in her jewelry requirements’ and note that she repeatedly requested last-minute alterations, lengthening and shortening the same necklace to suit different outfits,” Gerrish says. “Her behavior shows she was a collector who genuinely considered wearing the jewelry to suit her life, rather than displaying it as a trophy or status symbol for a particular event.”

Duke was also highly sensitive to color and light. “In one account, a Cartier salesman recalled that Duke rejected a pair of diamond earrings because ‘the diamonds were too yellow,’ explaining that they were intended to be worn ‘in the evening,’ when candlelight would exaggerate warmth in inferior stones. These comments highlight that her decisions were driven not by carat size or showiness, but by how well the piece performed visually, particularly under the new and dazzling electric light,” Daughters says.

What ultimately distinguishes Duke from many of her contemporaries is how actively she engaged with her jewelry. “Her jewelry was not static. Cartier correspondence shows that inherited or purchased pieces were continually reassessed, reset, or refined,” Daughters says. “Jewels were not treated as untouchable heirlooms, but as adaptable objects responsive to fashion, hairstyles, and social settings. As one Cartier associate noted, Duke ‘knew exactly what she wanted and, perhaps more importantly, what she did not want.’”

Doris Duke’s Most Notable Diamond Pieces

Duke’s diamonds were worn as social armour, deployed at society weekends, balls, and coronations. “They place her firmly within interwar café society, Hollywood glamour, and European luxury, yet at the same time, unmistakably American,” Gerrish says.

Daughters noted that there was a tremendous amount of symbolic meaning across her collection. “Fringe necklaces communicate movement and modernity. Tiaras express inherited authority and ceremonial identity. Belle Époque pendants suggest romance and ornamental excess. Duke’s collection spans these narratives, offering insight into personal identity across life stages. Diamonds act as a constant material presence while design context reshapes meaning.”

The Duke Watch by Cartier in Platinum, 1922

Duke inherited several extraordinary jewels from her mother, including this remarkable watch. In 1922, Duke’s father purchased a diamond wristwatch with a pearl band for his wife, Nanaline Holt Inman Duke, as a Christmas gift from the Manhattan jewelry house Charlton & Co. Following his death, Nanaline commissioned Cartier to update the watch, replacing the original band with an openwork platinum bracelet set with approximately eight carats of mixed-cut diamonds arranged in a cross motif—a design that reflected Cartier’s modern approach to structure and ornamentation during the early 1920s.

More than three decades later, Duke inherited the watch along with several other important jewels—and, reportedly, a fur coat as well—further cementing the role her mother’s collection played in shaping her own.

Belle Époque Cartier Pendant Necklace, 1908

This pear-shaped diamond pendant was another collaboration between Mr. Duke and Cartier, created for his wife (with Duke providing some of the diamonds). The necklace was originally designed as a sautoir—a long necklace typically worn low on the body and finished with a tassel, pendant, or dramatic drop. It was set in a delicate openwork frame of single-cut diamonds and finished with three pear-shaped diamond tassels and a suspended pearl measuring approximately 8.8 mm.

According to Christie’s, the piece ranks among the most important and beautiful necklaces of its era. For context, the Belle Époque—French for “Beautiful Era”—was a period in France spanning roughly 1871 to 1914, ending with the outbreak of World War I. It was characterized by optimism, peace, economic prosperity, and significant technological, scientific, and cultural innovation. Paris served as the epicenter for many of the era’s most influential works of art, literature, and music. In jewelry design, the period was marked by ornate diamond necklaces and pendants, dangling earrings, diamond- and pearl-set stomachers (triangular panels filling the front of a woman’s dress), jeweled tiaras and hair ornaments, as well as bold geometric brooches and chokers.

“Belle Époque craftsmanship remains central to valuation and conservation standards today. Platinum lacework, hand-finished settings, and integration of pearls with diamonds reflect labour intensity rarely replicated in modern production. Conservation prioritises structural stability while maintaining original articulation. Such pieces reward close study rather than distant display. Value stems from craftsmanship continuity as much as gemstone quality,” says Daughters.

The Cartier Diamond and Pearl Bandeau Tiara, 1928

Duke inherited this standout Cartier tiara from her mother, for whom it was made in 1924. The Art Deco bandeau—crafted in platinum and set with old European-cut diamonds and a row of central natural pearls—reportedly cost $23,000 at the time, a considerable sum that reflected both the quality of the materials and Cartier’s stature. In 2004, Cartier repurchased the tiara at the Christie’s sale of Duke’s jewels for $298,000.

Zuleika Gerrish notes that the design exemplifies Art Deco discipline, relying on strict geometric symmetry, a platinum structure, and diamonds chosen for their “gentle, atmospheric brilliance rather than maximum sparkle.” Platinum, she explains, was lighter and stronger than gold, allowing Cartier to create fine, flexible settings that sat low across the forehead. “Cartier mastered these properties to engineer bandeaux that sat securely and redefined how tiaras were worn in the 1920s,” she says, marking a shift away from upright, rigid forms toward designs that complemented the era’s sleek, shingled hairstyles.

That articulation, Gerrish adds, presents conservation challenges today. “This flexibility creates conservation challenges, as platinum links need to stay flexible without losing stability,” she noted, which is why restorations tend to be subtle and reversible, preserving Cartier’s original engineering rather than imposing modern stiffness.

The tiara is especially significant for the way it bridges two stylistic moments: the inherited grandeur of the Gilded Age and the pared-back modernity of Art Deco. Daughters emphasized that preserving such pieces requires sensitivity to both materials and intent. “Old European-cut diamonds differ from modern brilliance through deeper proportions and softer light dispersion,” he says, noting that restoration must respect original geometry. “Modern alterations risk flattening the visual rhythm,” he added, underscoring the cultural and educational value of maintaining authenticity.

Gerrish also points to Louis Cartier’s interest in Indian jewelry, visible in the openwork patterning and the disciplined use of diamonds as line rather than mass—a design language that, she notes, “translates remarkably well across generations.” The tiara’s lasting importance was further affirmed when it appeared in a Cartier exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 2025, where it was presented as a defining example of Cartier’s interwar modern style.

“The main advantage of period-specific design is restraint,” Gerrish says. “When well preserved, old European-cut diamonds and Art Deco proportions do not date a jewel; they give it enduring appeal.”

The Cartier Diamond Fringe Necklace, Early 1930s

A signature design of Cartier, the diamond fringe necklace was purchased in 1937 by Duke’s husband, James Cromwell—though it is widely assumed she offered a few hints along the way. The necklace features a platinum mounting set with old European-cut and baguette diamonds arranged in graduated tassels, making it a textbook example of Art Deco design and perfectly suited to the Newport-era aesthetic.

Of the necklace, Daughters says, “From a technical perspective, the Cartier diamond fringe necklace stands out through movement and precision. Fringe design demands uniform diamond matching and flawless articulation. Platinum structure supports fluidity without visual weight. Quality selection focused on consistency rather than individual dominance. Re-setting practices further highlight Duke’s priorities. Stones chosen for adaptability allowed multiple design lives without loss of brilliance or proportion. Such engineering reveals Cartier’s mastery, combined with a client engaged in long-term design evolution.”

Cartier Indian Diamond Necklace, Early 1930s

In 1971, Duke purchased three separate lots, comprising a diamond pendant clip, earrings, and a necklace, which were ultimately combined to create a larger, more dramatic necklace centered on an elaborate chandelier-style pendant. The necklace is composed of 12 foil-backed, table-cut diamonds, each framed by circular-cut diamonds and accented with delicately rendered foliate motifs. The central hanging diamond drop is mounted in platinum and measures an astonishing 15½ centimeters in length. Notably versatile, many of the diamond drops are detachable, allowing the necklace to be worn in multiple configurations.

During the Art Deco period beginning in the late 1920s, Cartier increasingly embraced Indian-influenced design. Jacques Cartier, Director of Cartier London and one of the three brothers who built the maison, was first exposed to Indian jewelry traditions during a trip to India in 1911. There, he formed relationships with prominent Indian clients who entrusted Cartier with resetting inherited gems into modern designs that still honored their cultural origins. As European interest in Indian aesthetics grew, Cartier sourced more Indian gemstones, including carved emeralds, rubies, and sapphires—elements that would become hallmarks of its interwar high jewelry.

The necklace later enjoyed a rare contemporary revival when it appeared on the red carpet, worn by Monica Bellucci at the Venice Film Festival in 2005. It then appeared on Bridget Moynahan at the Met Gala in 2006, underscoring the necklace’s ability to transcend both time and setting.

Tiffany & Co. Cushion-Cut Diamond Ring, 1935

Another piece originally belonging to Nanaline Duke, this 19.72-carat cushion-cut diamond ring features a central stone set above a pavé-set diamond gallery and shoulders, all mounted in platinum. The design reflects the elegance and restraint of 1930s American high jewelry, with Tiffany & Co.’s emphasis on proportion and refinement rather than excess.

The cut of the diamond is particularly significant, as it represents a transitional form between the Old Mine cut and the Old European cut—combining the softer geometry of earlier styles with improved light performance. The rough diamond is widely believed to have originated from the Golconda mines in India, famed for producing some of history’s most celebrated diamonds, including the Koh-i-Noor. Adding to the ring’s lore, Nanaline reportedly lost it while playing bridge at a party, only for it to be miraculously returned to her—a reminder that even the most extraordinary jewels can have surprisingly human stories attached to them.

Single Strand Emerald Necklace with Diamond Clasp, 1935

This beautiful necklace, composed of 53 graduated emerald beads, is brought together by an old European-cut diamond pierced plaque clasp centered on a cabochon emerald and mounted in gold and silver. The emeralds are widely believed to have originated from the Muzo mines in Colombia, long celebrated for producing stones of exceptional color and saturation.

Duke’s husband most likely purchased the necklace while the couple was traveling in India during their 1935 honeymoon, further marking her growing fascination with Eastern culture. The depth and richness of the emeralds’ color made a striking and unmistakable statement, setting the piece apart through both material quality and visual presence.

Cartier Diamond Hair Slides, 1937

Duke liked her accessories to feel cohesive, and these diamond hair slides are a perfect expression of that sensibility. Designed to coordinate seamlessly with the rest of the jewels worn as part of an ensemble, they reflect her attention to detail and overall harmony. The crescent-shaped design, set with circular- and baguette-cut diamonds and mounted in platinum, exemplifies the refined elegance of Art Deco design and Cartier’s mastery of balance and proportion.

Reinvention Through Resetting: Doris Duke and David Webb

Duke was never afraid to reset jewelry—including many inherited pieces—in order to improve them and reshape their narrative. This philosophy came into sharp focus through her work with David Webb, one of the most influential jewelry designers of the 20th century. Pieces such as her diamond and ruby earrings exemplify this collaboration. Webb was celebrated for his bold use of color and sculptural forms, qualities that aligned seamlessly with Duke’s willingness to reinterpret tradition.

“Resetting practices alter both physical form and historical narrative. Diamonds carry a geological age measured in billions of years. Human history adds layers through cutting, mounting, and reuse. Resetting acknowledges the permanence of material while allowing the evolution of expression. Each redesign adds authorship and intention rather than erasure,” says Daughters.

Webb also created original works for Duke, including emerald and diamond earrings that captured his bold design sensibility and her exacting taste—pieces shaped by a close client-designer relationship and her instinct for smart, intentional collecting.

The 2004 Christie’s Auction of Doris Duke’s Jewelry

In 2004, Christie’s New York held a landmark auction of Doris Duke’s jewelry collection, comprising approximately 150 pieces. The sale realized a total of $19.5 million. The top lot of the evening was the Cartier Belle Époque diamond and pearl pendant necklace, which sold for $2,359,500—setting a world auction record at the time for a diamond necklace by Cartier.

Simon Teakle, then head of Christie’s jewelry department in the Americas, said at the time, “The collection of heirloom jewelry that Doris Duke inherited from her parents, Nanaline and James B. Duke, complemented by her own purchases and creations over the years, surpassed all expectations.” Proceeds from the auction benefited the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, reinforcing Duke’s lifelong commitment to philanthropy.

“Auctioning the collection for a charitable legacy reframed ownership and meaning. Jewels transitioned from private adornment to public benefit. Diamonds retained material permanence while social function shifted. This act positioned jewellery as an asset with an ethical dimension rather than static inheritance. Legacy extended beyond display toward impact,” says Daughters.

The Enduring Legacy of Doris Duke and Her Diamonds

Duke was often described as the last Gilded Age socialite for a number of reasons. She came from old money, was raised to function as a social institution, and maintained grand estates like Rough Point, where she hosted prominent gatherings and established major charitable foundations. And while she lived an undeniably extravagant life, it was, for the most part, a private one—about as private as the “richest girl in the world” could manage. She rejected modern celebrity and mass publicity, aligning herself more closely with the values and discretion of the Gilded Age than with the social culture that followed.

Her approach to jewelry, like the rest of her life, favored individuality, freedom, and self-expression over rigid tradition. It was this philosophy that set her apart from many of her European and American aristocratic contemporaries.

“Within early-to-mid twentieth-century elite circles, the collection reflects American independence rather than European rigidity. European aristocracy favored the preservation of lineage symbols. American heiresses exercised greater freedom to modify and reinterpret. Duke exemplifies this divergence. Jewelry served as a personal narrative rather than a dynastic obligation. Such distinction continues to influence how collectors and historians read American jewelry history today,” says Daughters.

Duke ultimately outlived the social system that created her, but unlike many of her Gilded Age contemporaries, she remained at Rough Point until the end of her life. Today, the house operates as a museum open to the public and remains largely unchanged from the way Duke lived in it. Duke spent much of her life at Rough Point, filling it with priceless antiques and an extensive art collection that included works by Renoir and Gainsborough.

Yet she was never immune to practicality—or a bargain. Famously, her bed comforter was purchased at JCPenney. In a final flourish of eccentricity, she also kept two Bactrian camels, Princess and Baby, who arrived at Rough Point in 1988. (They spent their winters in a heated stall at her Duke Farms property in New Jersey and were reportedly fond of snacking on graham crackers.)

Doris Duke’s diamonds remain enduring symbols of elegance, authorship, and personal myth—objects that continue to intrigue and influence decades after her death. They were not merely accessories, but a tangible record of her extraordinary life and the independence with which she chose to live it.