Historic Diamonds / Royal Stories

Royal Splendor: The History Behind King Charles III’s Coronation Jewels

By Josie Goodbody, Updated October 8, 2025

A breakdown of each Crown Jewel being brought out for the Coronation of King Charles III.

King Charles III and Queen Camilla wave to the crowds from the balcony of Buckingham Palace following their Coronation at Westminster Abbey, with King Charles in the Imperial State Crown and Queen Camilla in Queen Mary’s Crown. (Getty Images)

The Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II on Saturday, June 2nd, 1953, was often referred to as the greatest public spectacle of the twentieth century. The first-ever televised British coronation captured the attention of people across the world with its opulent but deeply religious pageant. Seventy years later, following the death of Her late Majesty in September 2022, the crown has passed to her son, King Charles III. His coronation, alongside Queen Camilla, marks a new chapter in the history of the British monarchy.

Meet the Expert

- Josie Goodbody is a jewelry historian, novelist, and communications specialist with a passion for storytelling and the world of high jewelry.

- Goodbody is the author of the Jemima Fox mystery series, blending intrigue with dazzling jewels, and her work has appeared in the Daily Mail and Rapaport.

But how did this extraordinary ceremony, barely altered in over a millennium, come to be, where is it, what happens, and what is the regalia brimming with jewels about?

The History of British Coronations

The concept of coronations, anointing a new monarch with Holy Oil, presenting them with regalia, and crowning them, was well established by the 7th century. Since 1066, beginning with William the Conqueror, all coronations have taken place in London’s Westminster Abbey. On May 6th, 2023, Charles became the fortieth monarch to be crowned in this fabulous and historical abbey.

The coronation followed the same pattern as it did all those centuries ago. There are very clear instructions, laid down in a beautifully decorated 1382 manuscript called The Liber Regalis (Royal Book). This magnificent medieval tome, kept since its creation in Westminster Abbey, indicates instructions in Latin, with detailed, colorful illustrations for the coronation of a monarch.

What Happens During the Coronation Ceremony?

While the coronation followed centuries-old tradition, Charles III introduced subtle but significant modernizations. Sustainability was a key theme: both the King and Queen Consort reused historic garments and crowns rather than commissioning entirely new ones. The guest list and procession were also streamlined compared to Elizabeth II’s coronation, with 2,000 attendees instead of 8,000 and a shorter service designed for contemporary audiences.

However, as decreed in the Royal Book, the all-important Crown Jewels and Regalia overflowing with natural diamonds were still at the heart of the ritual. So let’s revisit what happened during the coronation.

On the eve of the coronation, the Regalia was brought from the Tower of London to Westminster Abbey and kept overnight in the Jerusalem Chamber, guarded by Yeoman Warders and ready for the following day’s proceedings.

At 11 am on Saturday, 6th May, the King entered Westminster Abbey with Queen Camilla after being driven from Buckingham Palace in the Gold State Coach.

The first part of the service was known as The Recognition and The Oath, when the King was presented to the people and made promises to them and to God. Following the oath, he sat in the Coronation Chair, which faced the High Altar, for the third and most religious part of the service, the Anointing.

The Crown Jewels at the Coronation

Wearing a simple white sleeveless linen garment, symbolizing purity before God, the Holy Oil was poured from the Ampulla into the Coronation Spoon and, with two fingers, the Archbishop of Canterbury anointed the King’s head, chest, and hands with the oil.

After this came The Investiture, when the monarch, dressed in robes of gold cloth, received the Sovereign’s Orb; the Sovereign’s Sceptre with Cross and the Sovereign’s Sceptre with Dove; and the Sovereign’s Ring. Finally, the Sword of State was placed on the altar and the monarch was crowned with the incomparable St Edward’s Crown, which he wore for only a minute before changing back into the robe of State and donning the Imperial State Crown.

The last part of the ceremony was the Enthronement and the Homage, when his son, the Prince of Wales, knelt before Charles III, placed his hands on his knees, swore allegiance, touched the Imperial State Crown, and kissed his right hand.

Alongside her husband, the Queen Consort was crowned with Queen Mary’s Crown, chosen from the Royal Collection’s Queen Consort Crowns. The infamous Koh-i-Noor, which had been at the center of the crown, was removed and replaced with Cullinans III and IV in honor of Her late Majesty, who so often wore them as a brooch, known as Granny’s Chips; Cullinan V was also set in the 1910 crown. Queen Camilla also carried items of regalia such as sceptres and a ring.

The King and Queen then left the Abbey, wearing their crowns, and proceeded back to the Palace, followed by the rest of the Royal Family.

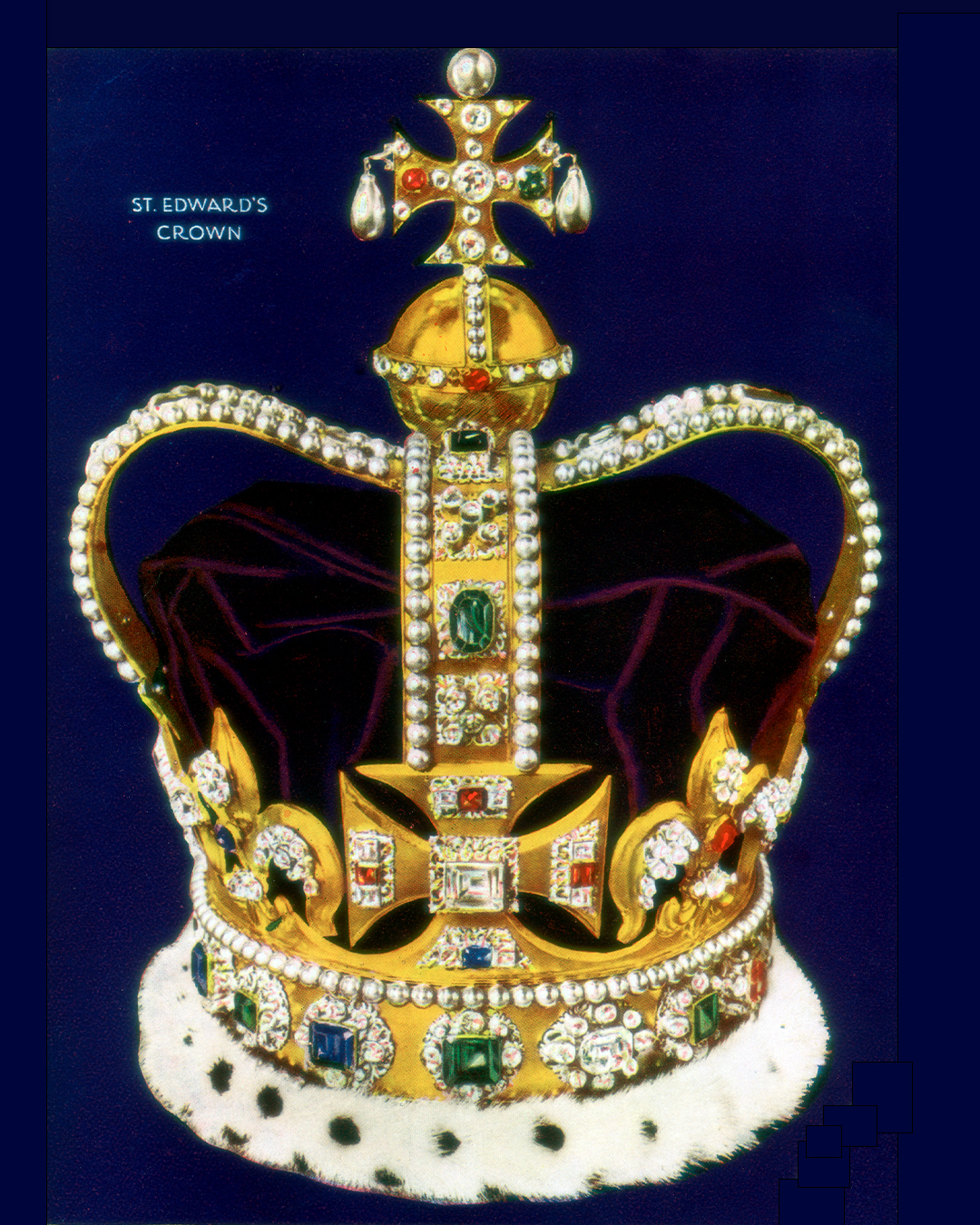

St. Edward’s Crown: The Sacred Coronation Crown

The St Edward’s Crown is the most sacred item of the Royal Regalia and is named after the penultimate Anglo-Saxon king, Edward the Confessor. It will only be on the regent’s head for mere moments during the coronation.

On his deathbed in 1066, King Edward asked the monks of Westminster Abbey to keep his crown and other royal ornaments, in perpetuity for all future monarchs. A century later, he was canonized, and his regalia declared holy relics. The crown eventually became known as St Edward’s Crown.

In 1649, when King Charles I was executed and the monarchy abolished, St Edward’s Crown and the rest of the Royal Regalia were either broken up and sold or melted down.

Eleven years later, Charles I’s exiled son—Charles II—became king, and he deemed that the majesty of monarchy needed to be celebrated in a flamboyant way; new coronation regalia was needed. The cost to purchase precious stones was too much, so they were instead hired and set in the gold framework, said to incorporate gold from the original.

For more than two centuries, St Edward’s Crown rested on Westminster Abbey’s high altar during the ceremony, as it was considered far too heavy to wear at 2.6 kg. It was not used again until the coronation of the King’s great-grandfather, George V, in 1911—thankfully reduced in size and weight, though the jewels were still hired.

For the subsequent coronation in 1937, George VI, the King’s grandfather, bought the 444 gemstones, and the indomitable diamonds, rubies, amethysts, sapphires, garnets, topazes, and tourmalines are still there today.

The Imperial State Crown and Its Legendary Diamonds

The Imperial State Crown, which is in more frequent use, was created for the coronation of George VI in 1937 by Garrard and is probably the most significant gem-set piece of regalia in the world. This is thanks to more than a handful of historically weighty gemstones.

So with 2868 diamonds, 17 sapphires, 11 emeralds, and 269 pearls, it’s not surprising that several are steeped in as much legend as St Edward’s Crown.

Out of the 2868 diamonds, one is of particular importance with a story we know is absolutely not a legend. The enormous cushion-shaped diamond, at the front of the band, is the Cullinan II, it was given to Edward VII two years after being discovered in Thomas Cullinan’s Premier mine in South Africa in 1905. It is still the largest and most spectacular diamond ever found. It was given to the British monarch after the Boer War, and from it were cut nine large diamonds – the two largest are set in the Sovereign’s sceptre (see below) and the Imperial State Crown.

The Coronation Regalia: Symbols of Monarchy and Faith

The Sovereign’s Orb

The Sovereign’s Orb—again made for Charles II in 1661, this integral piece of regalia symbolizes the Christian world. The glorious golden globe is surmounted with a ‘monde’ created as an amethyst and cut in an octagonal step-cut above which stands a cross, set with rose-cut diamonds, an emerald on one side, and a sapphire at the center on the reverse, and bordered with lines of pearls.

Bands, set with rubies, sapphires, emeralds, and pearls, divide the surface of the sphere into three, which is supposed to be the three continents that were known at the time of its original creation. In total, this piece of regalia, placed on the high altar at the moment of crowning, is set with 365 rose-cut diamonds to represent each day of the year.

The Coronation Spoon

The Coronation Spoon is the only remaining item of the original medieval regalia. It was described as antique even in 1349 when first recorded as part of St Edward’s Regalia at the Abbey. Like St Edward’s Crown, this is probably one of the most important religious items of the regalia, as it is used for anointing the sovereign with holy oil, poured from the Ampulla (see below) onto the spoon. This is the most solemn and deeply religious part of the ceremony.

The Holy Ampulla

The Ampulla, from the Latin for ‘spherical flask’, holds the holy oil, as described above. This magnificent item of the regalia is in the form of a glorious golden eagle standing as though about to take flight; beautifully depicted feathers fan out along fully spanned wings of the bird, who stands proudly on a circular podium of foliage, sculpted in gold.

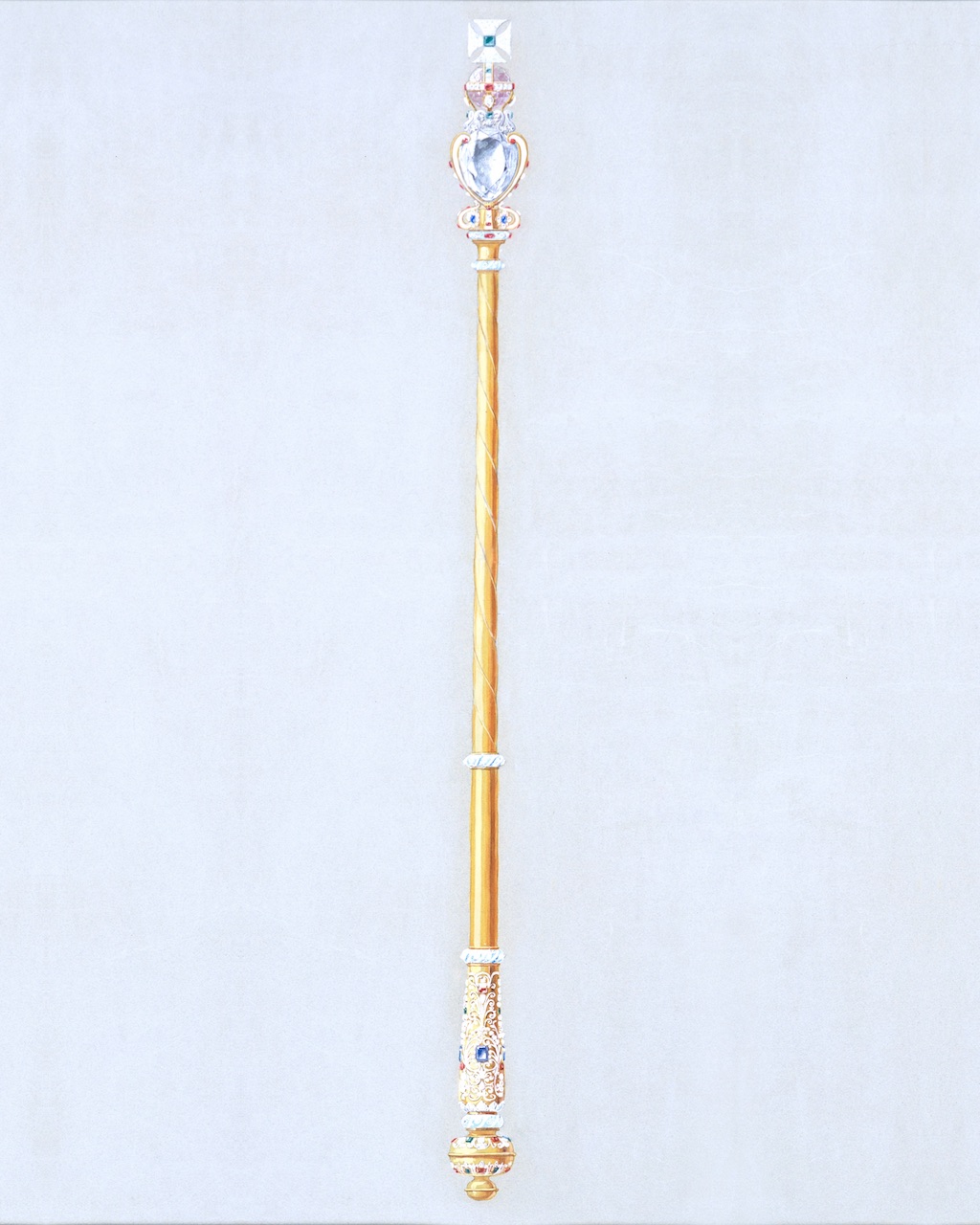

The Sovereign’s Sceptre with the Cullinan Diamond

The Sovereign’s Sceptre with Cross is a symbol of authority and, as its name explains eponymously, sovereignty. Like most of the regalia, the sceptre was originally made for Charles II in 1661 and consists of a gold rod created in three sections with enameled collars at each intersection. Over the centuries, it underwent many alterations, most significantly in 1910 by the Crown Jewellers, Garrard, so as to receive the Great Star of Africa, aka Cullinan I (the largest diamond cut from the largest diamond ever found).

The heart-shaped structure that securely holds this 530.2-carat flawless diamond was hinged because, according to Caroline de Guitaut, the Deputy Surveyor of the Royal Collection: “Queen Mary, with great foresight and obviously a great lover of jewels made very, very sure that both Cullinans I and 2 could be detached from the sceptre and state crown, so that she could wear them together as a brooch – yes together, 1000 carats of diamonds!”.

Above the Cullinan’s casing are enamelled brackets set with step-cut emeralds, holding a faceted amethyst ‘monde’ (sphere) with table and rose-cut diamonds, rubies, spinels, and emeralds set in gold around the amethyst sphere; and then above that is the cross set with more diamonds, an emerald on the back, and a large table-cut diamond on the front. The base of the gold rod is also beautifully decorated with further enamel work and set with 99 rose-cut diamonds, sapphires, rubies, and emeralds.

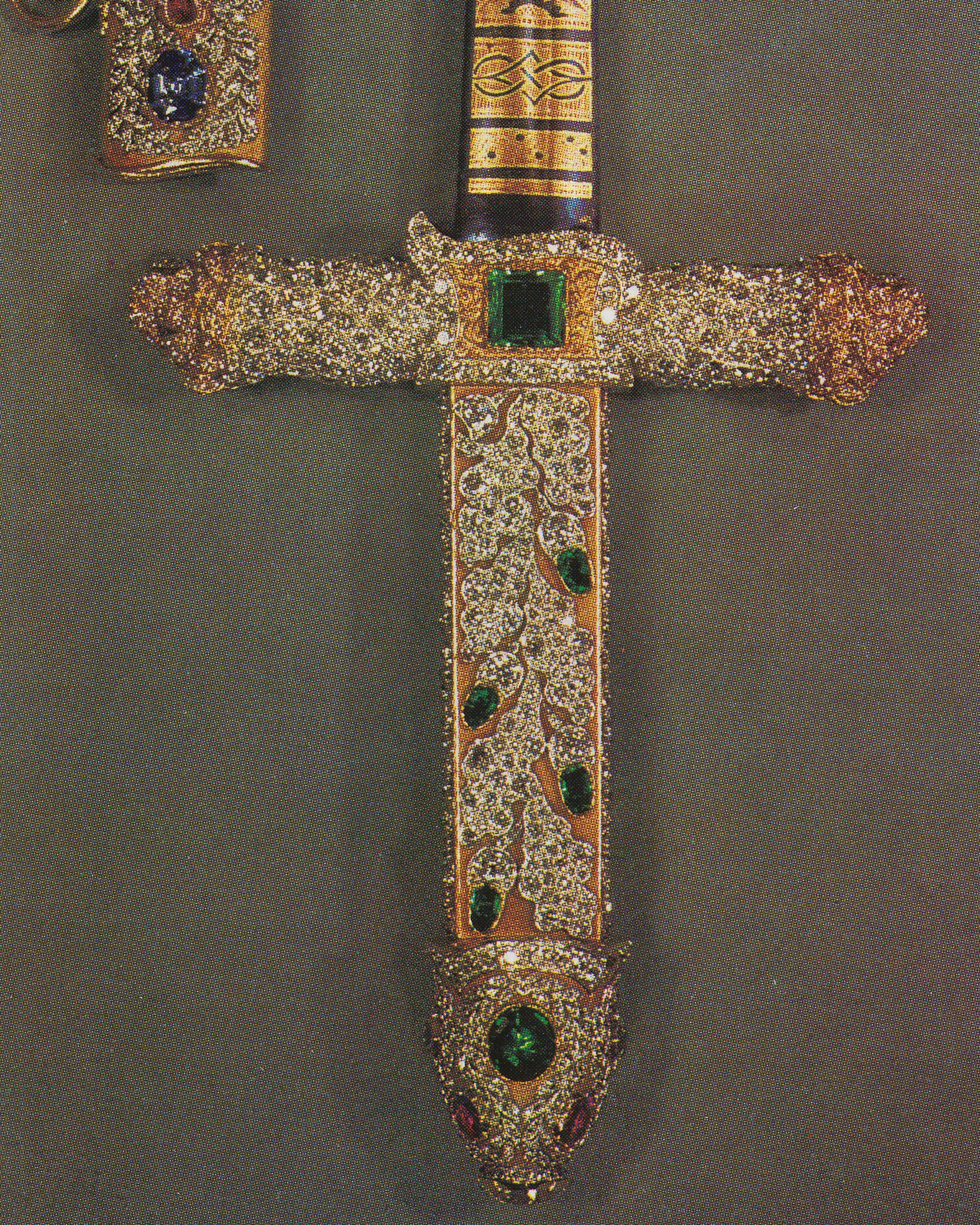

The Jewelled Sword of Offering

The Jewelled Sword of Offering, an oft-forgotten item of the regalia, is in fact one of its most beautiful. It was created for and under the instruction of George IV in 1821. As we learned above, the Sword of Offering is given to the monarch during his Investiture – alongside the Orb and Sceptre.

The blade of the sword is decorated in blue and gilt steel with the emblems of the British Isles – roses, thistles, and shamrocks. The crosspiece of the handle is gold and set densely with diamonds, with a rectangular cut emerald on one side and an octagonal cut emerald on the reverse. Lion motifs, with ruby-set eyes, are at either end of the crosspiece. The grip is set with diamonds in the form of sprays of oak leaves, with emeralds depicting acorns. The pommel is set with diamonds, rubies, and an emerald.

The sword’s scabbard (case) is made from leather, covered with gold sheet, and lined with red silk velvet. It is superbly decorated on either side with roses, thistles, and shamrocks in diamonds, rubies, and emeralds. The top of the scabbard is mounted with blue and yellow sapphires and a ruby amongst glittering diamonds, whilst the bottom (the chape) is set with further diamond oak-leaf sprays and emerald acorns and an opulent large turquoise oval cabochon on each side.