< Culture & Style / Designer Profiles

The Human Art of Cutting a Triple X Diamond

Get to know more about the master cutters who help bring Triple X diamonds to life.

By: Brandon Borror-Chappell, November 12, 2025

I don’t possess much technical knowledge about diamond cuts, but I know that when my wife, Laura, and I are on an airplane, I like to look at the light pattern that the engagement ring I got her scatters on the wall next to her (she always takes the window seat). The dancing pattern that hypnotizes me is the refraction of hundreds of years of evolving craftsmanship.

That realization sent me in search of the human side of cutting natural diamonds: how people come to this work, what it means to them, and what it reveals about us. Along the way, I spoke with Willy Lopez, master cutter at William Goldberg; Briony Raymond, designer and estate jeweler; and Stefano Canturi, the visionary behind Cubism-inspired jewelry.

Ahead, discover how the art and science behind a Triple X diamond reveal the brilliance—and humanity—within every cut.

Meet the Experts

William “Willy” Lopez is a master cutter whose journey with the William Goldberg family began in the early ‘90s when he cut emerald-cut diamonds for the factory as a contractor. Then, in 1992, he joined the company, bringing his exceptional skills in-house.

Briony Raymond is the founder of her namesake New York atelier. She is a distinguished expert in fine jewelry, renowned for her bespoke designs and curated estate collections.

Stefano Canturi is an acclaimed Australian jeweler and designer renowned for his bold, architectural settings and modern heirloom creations. His work blends art and emotion, with each natural diamond engagement ring designed to celebrate individuality and love.

What Is a Triple X Diamond?

According to the Gemological Institute of America (GIA), a Triple X diamond is a trade term referring to round brilliant diamonds that have been determined to have an Excellent cut, with both polish and symmetry noted on their grading reports. While GIA doesn’t use the term Triple X diamond, it’s widely used among jewelers. Essentially, a Triple X diamond is Triple Excellent when accounting for cut, symmetry, and polish, with the best possible craftsmanship.

The Craft of Diamond Cutting Passed Down

As I wound my way down through the streets of Manhattan, closer and closer to William Goldberg Way in the Diamond District to visit the eponymous atelier, I thought about the twists and turns of my own life. As best I can recall, I never encountered any kind of magic portal that might have led me into the jewelry business. For Willy Lopez, the path into diamond cutting was almost inevitable. “Usually, you get into the business through a family member,” he told me. His father, trained through a U.S. initiative called Operation Bootstrap, became a diamond cutter in the 1940s before moving to New York in 1947.

As a child, Willy occasionally visited his father’s shop and loved the tools, though he never considered it a career path. His older brother had tried cutting and disliked it. But in 1970, after quitting a job in Brooklyn, he decided to dip his toe into the family business. Willy first encountered synthetic substitutes such as YAG and cubic zirconia. “You take something that looks like nothing, like a piece of rock candy, and turn it into something beautiful,” he said. “When I moved on to natural diamonds, it was much more difficult, but I liked the creativity and the techniques.”

When the Stone Speaks

Willy describes the work almost like sculpture. “You cut little facets in the skin of the rough and look inside. The diamond tells you what you should do with it. The natural shape, the imperfections, the grain—if you take a stone that should be a pear and cut it into a marquise, you’re wasting it.”

It reminded me of Michelangelo’s quote: “I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free.” Willy smiled at the comparison.

Of course, some diamonds carry a special kind of awe. Willy has handled some of the world’s most famous stones, including the Moussaieff Red and the Pumpkin Diamond. He recalled receiving the rough for the Pumpkin in 1992. “It didn’t look like it was going to be much,” he said, rubbing his cheek and staring off over my shoulder. “But when I cut into it and took off some of the skin… You know, when you see a sunrise, when the orange light comes shooting over the horizon? That was a beautiful stone.”

The Making of a Modern Jeweler

If Lopez grew up with the tools of a cutter, Briony Raymond arrived by a different road. She had fallen in love with Paris while studying art history, and to stay there, took a job in finance. “I could do it, but I didn’t love it,” she said. “What I realized was that I loved helping people understand the value of what they had. I loved forming those relationships. And I thought, maybe there’s a more fun way to do that.”

After her father’s passing, she returned to New York and secured a position at Van Cleef & Arpels. “My love for jewelry and diamonds at that point was all osmosis, just my obsession with aesthetic beauty. I didn’t have commercial training, so I approached it like this: I know nothing, you are the experts, please teach me.”

That wide-eyed humility, she believes, was her secret weapon. “I became completely obsessed, learning all about diamonds, gemstones, and workmanship at this elite level. My perspective evolved from, ‘I love that, that’s beautiful,’ to ‘I know why this matters to a collector.’”

What a Diamond Cut Reveals

Raymond sees cut as a language of personality. “A cushion cut—pillowy, sparkly, tinkly—that’s someone who likes to make an entrance,” she explained. “An emerald cut, with its long, linear facets, reflects light in and out like a rhythm. A brilliant cut is a riot of twinkle and scintillation. One dazzles; the other holds the eye.”

Even subtle details matter. Raymond explains, “If a stone is cut to be bottom-heavy, with more weight hidden underneath, that’s quiet and understated. A shallower stone with a larger table is louder and more extroverted. I’m a more-is-more kind of girl. I just love a big, beautiful, sparkly natural diamond.”

Raymond’s heart, though, belongs to antique stones. “The big faceting patterns from the 1870s to the early 20th century have this delicious, twinkly yumminess,” she said, laughing at her own food metaphor. “They were cut by hand, often imperfect, a little asymmetrical. But that imperfection shows the hand of the cutter.” I wondered if it was at all like listening to an old-timey song recorded with old equipment. “YES! It’s so transportive, so charming, so intoxicating.”

The Diamonds That Stay with You

When asked about favorites, Lopez immediately named the Hope Diamond—one he hasn’t yet touched but dreams of holding. Raymond didn’t hesitate either: a 16-carat antique emerald cut diamond, probably from the 1920s, currently in her care. “It has deep cut corners, like something Elizabeth Taylor would have worn,” she said. “It’s absolutely my favorite stone I’ve ever had.”

For her, the joy lies as much in the history as in the beauty. “Here’s this stone, cut and set 200 years ago. It’s been the prized possession of six different people, imbued with their love and dreams, and now I get the privilege of stewarding it.”

The Quiet Power of Design

That same sense of restraint and history underpins the work of Stefano Canturi. “What I love about diamonds is that no two are ever the same,” he told me. “You’re working with something born billions of years ago, and when it’s cut, that’s when its soul is revealed. For my designs, I look for character, geometry, and elegance. That’s why I lean toward carré and baguette cuts—they’re quietly powerful—architectural but sensual too. An emerald cut has that same kind of allure. It doesn’t sparkle for attention; it holds your gaze. The women who are drawn to these cuts have a quiet strength and timeless style.”

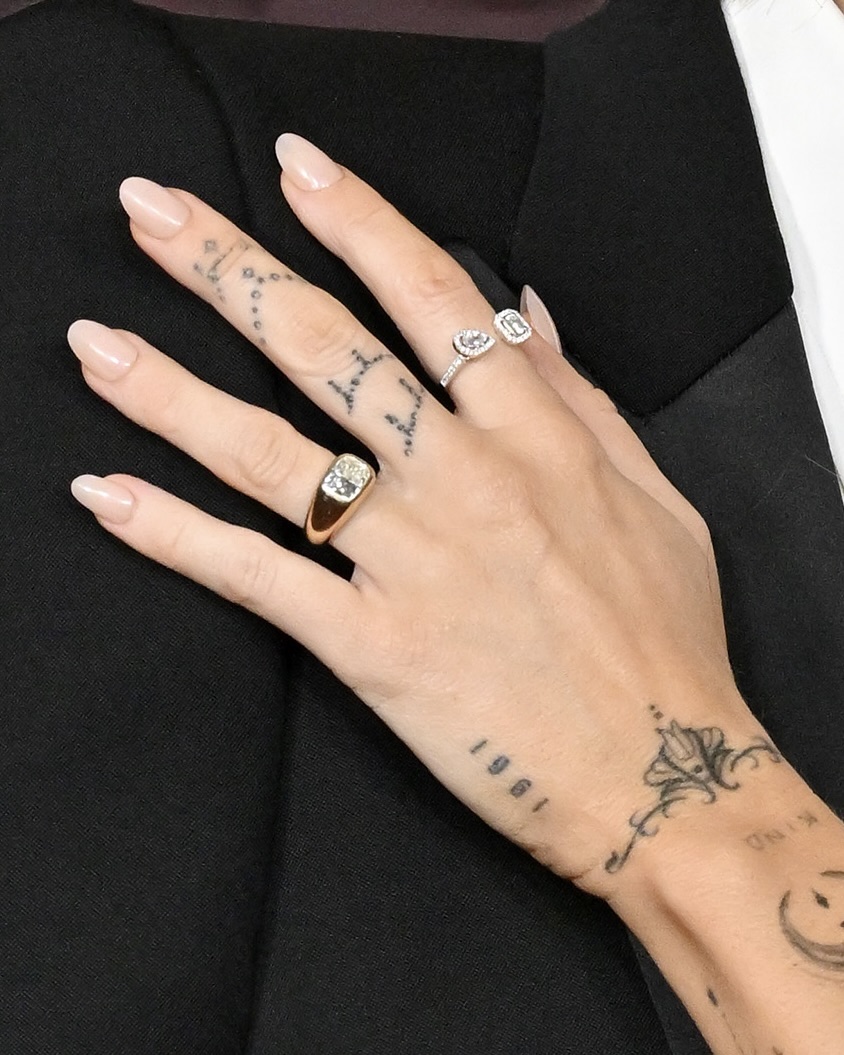

Raymond, meanwhile, speaks of the intimacy between jewel and wearer. “Jewelry is worn against your skin. It’s a talisman, a way of communicating how you want to be seen,” she said. That’s why she feels equal gratitude whether her pieces are worn by Rihanna or by a first-time collector. “There’s no shortage of beautiful jewelry out there. So, whenever anyone chooses something we’ve made, I feel endlessly grateful. It never gets old.”

That philosophy has carried her from Paris classrooms to the ateliers of Van Cleef, and on to her own clients that span celebrities, collectors, and families alike. Her “superpower,” she says, is knowing how to listen. “I get to know someone, figure out what suits them, and I get so much pleasure from that.”

Brilliance, Revealed

Diamonds, in their raw state, are rough and unyielding. Yet through patient attention, cutters and jewelers coax out their hidden light. What struck me most in speaking with Lopez, Raymond, and Canturi is that none of them views the work as imposing their will. Instead, they speak of listening—whether to the rough stone itself, to centuries of craft, or to the desires of a client.

Maybe that’s why, even on an airplane wall, the light from Laura’s ring feels bigger than sparkle. It’s billions of years of earth, centuries of artistry, and the devotion of people who believe that every diamond—like every person—has brilliance waiting to be set free.