< Historic Diamonds / Royal Stories

Wallis Simpson’s Jewelry Legacy: Power in Exile

A deep dive into the Duchess of Windsor’s breathtaking collection of natural diamond jewels.

Published: January 8, 2025

Written by: Meredith Lepore

Wallis Simpson, the Duchess of Windsor, could have just been known as the American woman who caused the abdication of King Edward VIII. It was an unprecedented political crisis that modern England had never faced before (but they would face again), and it shook the Royal Family. But Simpson was more than just “that woman,” and her exquisite jewelry became an intricate part of her story.

“Wallis Simpson used jewelry as a form of self-expression and understood early on that power was not simply inherited—it could be demonstrated,” says Zuleika Gerrish, an antique, vintage, and fine jewelry expert, gemmologist, and co-founder of Parkin & Gerrish in England. When she first met the Prince of Wales in 1931, it was not her beauty or her jewels that distinguished her, but her wit.

Asked whether she missed American central heating, Simpson replied, “Every American woman who comes to England is asked the same question. I had hoped for something more original from the Prince of Wales.” The remark, Gerrish notes, signaled intelligence, confidence, and a refusal to be belittled—qualities that would later shape her jewelry choices as clearly as her speech.

Meet the Expert

- Zuleika Gerrish is an antique, vintage and fine jewelry expert as well as a gemmologist and co-founder of Parkin and Gerrish with her husband Oliver.

- She is a qualified FGA (Fellow of the Gemmological Association) and DGA (Diamond Member), and is training to become an IRV (Institute Registered Valuer) through the National Association of Jewellers.

- Zuleika is also a member of LAPADA and CINOA, and a member of the Society of Jewellery Historians. Alongside running Parkin & Gerrish, she lectures on historic jewelry, sharing her expertise with new audiences.

Ahead, a look at Wallis Simpson’s very unique life and her even more unique and priceless jewelry collection, including her patronage with Cartier and Van Cleef & Arpels. Each piece in the collection tells an original story and has a spirit of defiance behind it.

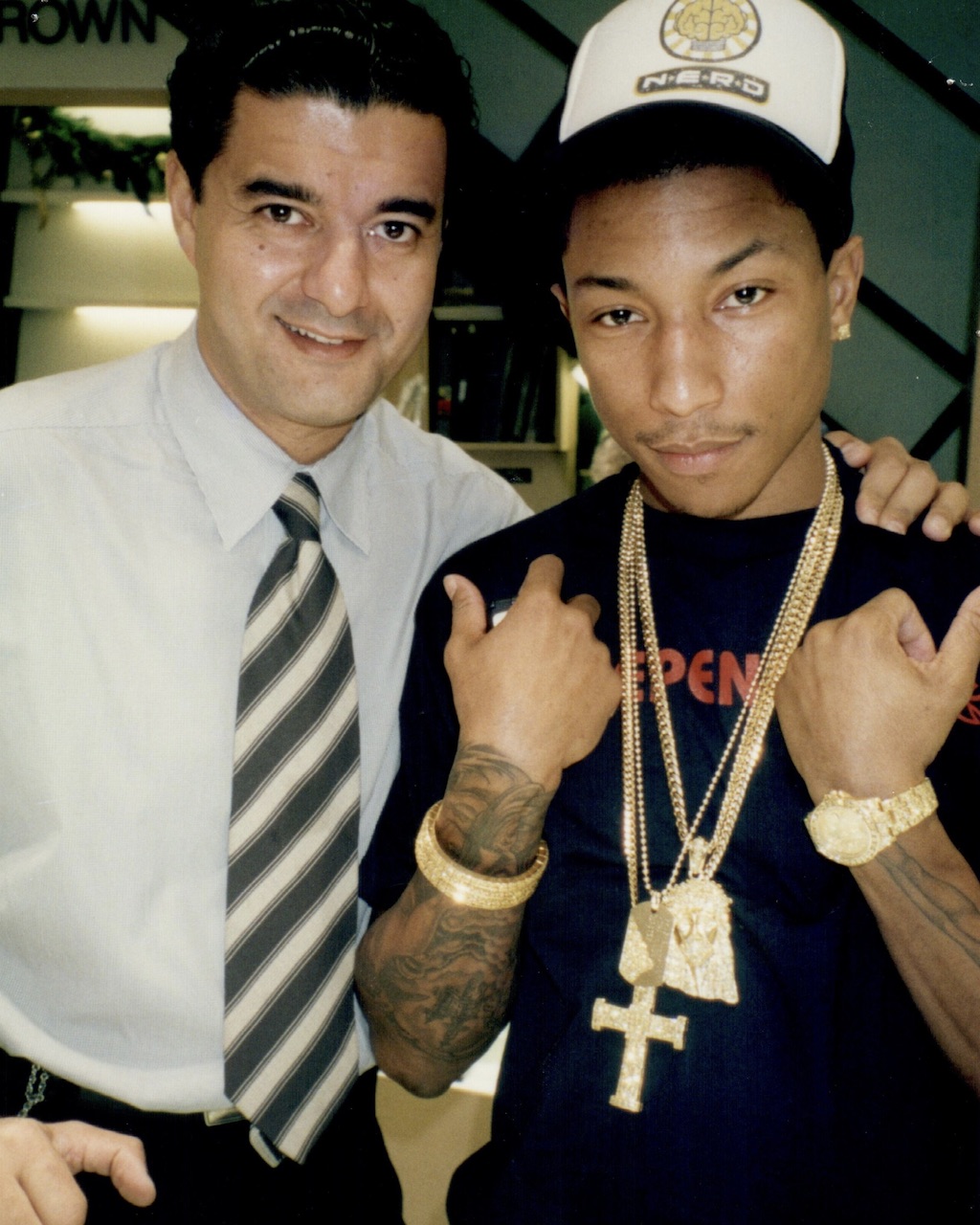

Wallis Simpson Before the Crown

The socialite who would become Wallis Simpson was born Bessie Wallis Warfield on June 19, 1896, in Blue Ridge Summit, Pennsylvania, and grew up in relatively modest circumstances in Baltimore. She steadily climbed her way into high society, a reminder that not every socialite is born—but, in the classic American way, can be made—most notably through her second marriage to Ernest Simpson, a British shipping executive. Over time, she evolved into a formidable style icon and cultural figure, known for her sharp wit, uncompromising confidence, and refusal to apologize for who she was.

Wallis Simpson famously embraced the maxim “Never explain, never complain,” a phrase that neatly encapsulates her approach to life. She also articulated one of the most infamous, if unspoken, mottos of elite society: “You can never be too rich or too thin”—a line that reveals much about her worldview and was reportedly engraved on a pillow in her home.

“Often dismissed as flippant, the line reveals her acute understanding of appearance as power. Discipline, control, and polish were survival tools. Jewelry, like fashion, operated within that economy of visibility. She did not wear jewelry; she was making a statement,” says Gerrish.

Wallis Simpson met then–Prince Edward in the early 1930s at a party hosted by his mistress. Though she was still married at the time and he was second in line to the throne, the two became fast friends—and then something more—much to the horror of the British royal family.

In January 1936, King George V died, and Edward ascended the throne. That October, Wallis Simpson filed for divorce from Ernest Simpson, citing his extramarital affairs—though the deeper motivations were widely understood. Two months later, Edward informed the Prime Minister of his intention to marry Simpson, even if it meant abdicating the throne. His mother, Queen Mary, urged him to end the relationship, but Edward made his position clear: he would not remain king unless Wallis were his wife.

Edward chose love over the crown, proposing to Wallis with a 19.77-carat emerald ring by Cartier, engraved “WE are ours now 26 X 36” (more on that later), before signing the Instrument of Abdication. His brother Albert became King George VI and later granted Edward the title of HRH Duke of Windsor.

The couple first moved to France, then to the south of the country when the Germans invaded, before relocating to Spain. Later that year, they settled in the Bahamas, where they remained for the duration of the war—a pleasant exile, all things considered. In 1940, the British government appointed Edward as Governor of the Bahamas, a British territory at the time, a posting he held until 1945, according to the BBC. In 1953, the Duke and Duchess (along with their many pugs) returned to France, settling in Paris near the Bois de Boulogne, where they would spend the remainder of their lives.

It was during exile that Wallis Simpson began to author her own jewelry identity, starting with her engagement ring, according to Gerrish. By choosing a colored stone, the couple made their official debut with a radical choice. “Emeralds were fragile, unconventional, and deeply colored—everything a traditional royal engagement ring was not. From the outset, Wallis’s jewelry rejected convention in favor of emotion, individuality, and bold color. The ring announced not only a proposal, but a philosophy,” she says.

Twenty years later, to mark their anniversary, the ring was reset in yellow gold and framed by natural diamonds. Gerrish notes that this detail is also significant. “The act of resetting matters: her jewels were not static trophies, but living objects, evolving with the marriage itself. Jewelry marked time, endurance, and survival, and more importantly, publicly affirmed that they were still together after all that had passed,” she says.

Wallis Simpson’s After Abdication: Jewelry as Power

After becoming part of one of the 20th century’s most scandalous love stories, Simpson’s jewelry took on deeper meaning, serving as a declaration of autonomy and a life lived beyond the reach of the royal family. Each piece asserted identity, legitimacy, and a determination to thrive after abdication.

“Simpson’s jewels were instantly legible: sculptural, witty, modern, and deliberately worn against simple couture so that nothing diluted the message. A bold brooch, oversized earrings, or a dramatic bib necklace functioned almost like a punctuation mark! This was not a royal “collection” built on inheritance or tradition, but a portable biography, authored in stones, inscriptions, and motifs,” Gerrish says.

Wallis Simpson’s visual language remained remarkably consistent despite enormous social and economic change. Before the war, jewelry signaled proximity to power; afterward, prevailing tastes shifted toward restraint and sobriety. “Whether before or after the war, she continued to favour scale, color, and presence: emeralds, sapphires, amethyst and turquoise, panthers poised on monumental stones. Shopping habits changed; her style did not,” said Gerrish. Even as her preferred and most frequent collaborator, Cartier, moved toward more restrained designs, Wallis refused to soften or dilute her aesthetic.

Below, we delve into other defining pieces of Wallis Simpson’s collection.

The Defining Jewels of Wallis Simpson

Van Cleef & Arpels Ruby Bracelet (“Hold Tight”), 1936

Given to Wallis Simpson in 1936, during the most uncertain period of her relationship with Edward VIII, the Van Cleef & Arpels ruby bracelet engraved “Hold Tight” reads as both a romantic gesture and an emotional instruction. At the time, Wallis was still in the process of divorcing Ernest Simpson, and the future of her relationship with Edward—let alone his reign—remained unresolved. Set with vivid rubies, a gemstone she would come to favor deeply, the bracelet functioned as a talisman of endurance. Its message was intimate yet public, literal yet loaded: a directive to persevere. In hindsight, it feels like a prologue—an object that captures anticipation, restraint, and emotional tension before the irrevocable choices that would follow.

Cartier Cross Charm Bracelet, 1934–1944

Wallis Simpson’s cross charm bracelet was crafted by Cartier over a ten-year period, from 1934 to 1944, and stands as one of the most emotionally layered jewels in her collection. Executed in platinum and diamonds, the bracelet suspends nine gem-set Latin crosses, each rendered in colored stones—sapphires, emeralds, rubies, aquamarines, amethyst—and many engraved with dates and inscriptions marking significant moments in her relationship with Edward VIII. Worn frequently, including on her wedding day, the bracelet functioned less as a religious object than as a personal chronicle, recording love, endurance, and survival in exile.

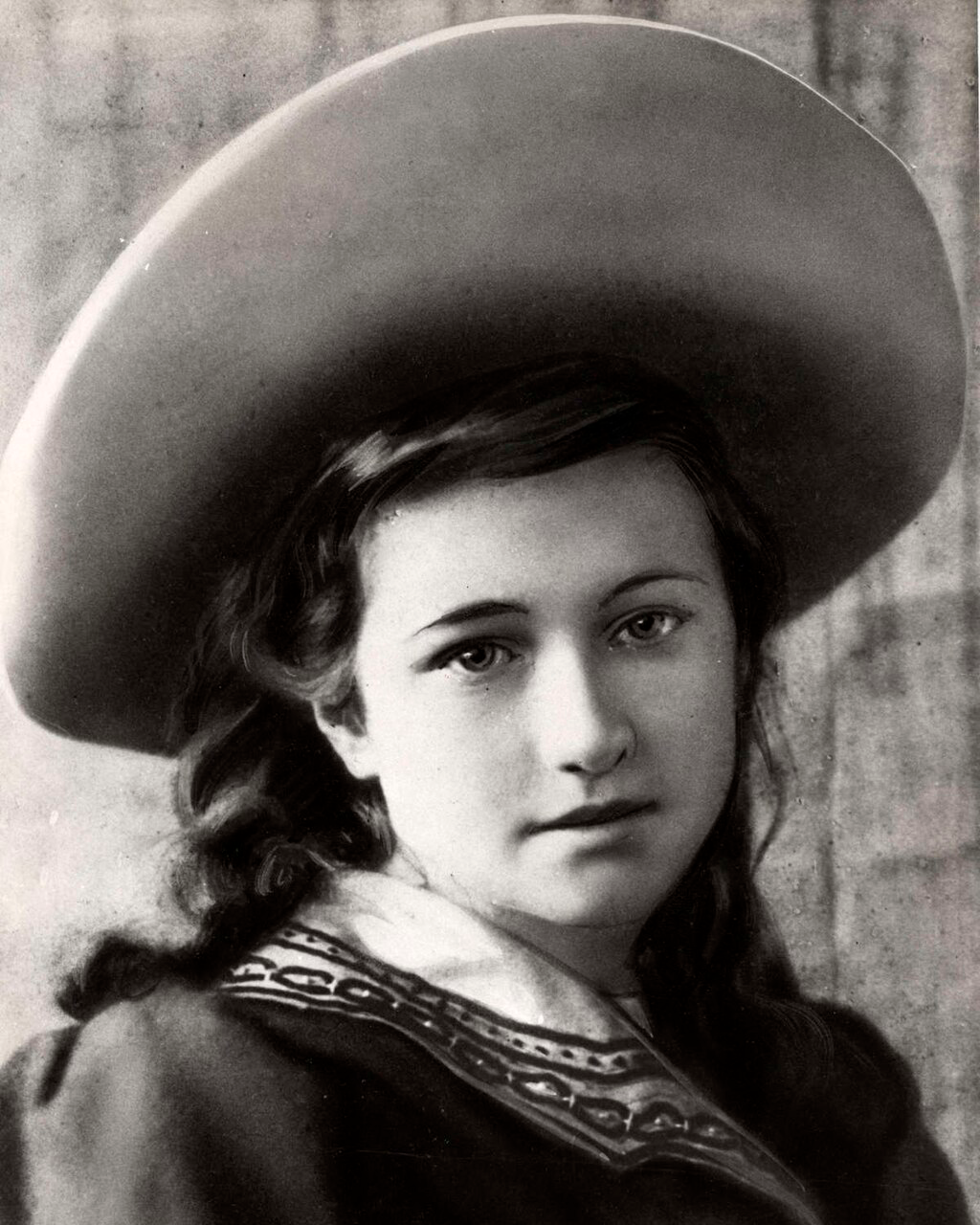

Van Cleef & Arpels Ruby and Diamond Feather Clip, 1936

This feather clip formed part of a ruby parure commissioned by Edward VIII, which also included a necklace and bracelet. Designed by Van Cleef & Arpels, the bejeweled clip takes the form of two stylized, intertwined plumes—an unmistakable symbol of two lives bound together yet unrestrained.

Beyond its emotional resonance, the piece marked a significant technical achievement for the maison. It is among the earliest jewels to employ Van Cleef & Arpels’ pioneering invisible setting, a technique developed in the early 1930s. Here, rubies are precisely grooved and mounted onto hidden rails, allowing the stones to sit seamlessly against one another without visible metal prongs. The process is exceptionally demanding, but the result is astonishing—an almost illusionistic surface of uninterrupted color.

Paired with natural diamonds, the invisibly set rubies give the clip a sense of lightness and fluidity that belies its complexity. More than a decorative flourish, the feather clip helped establish Wallis Simpson’s emerging use of jewelry as a tool of self-definition—objects chosen not only for beauty, but for their ability to project control, unity, and intent.

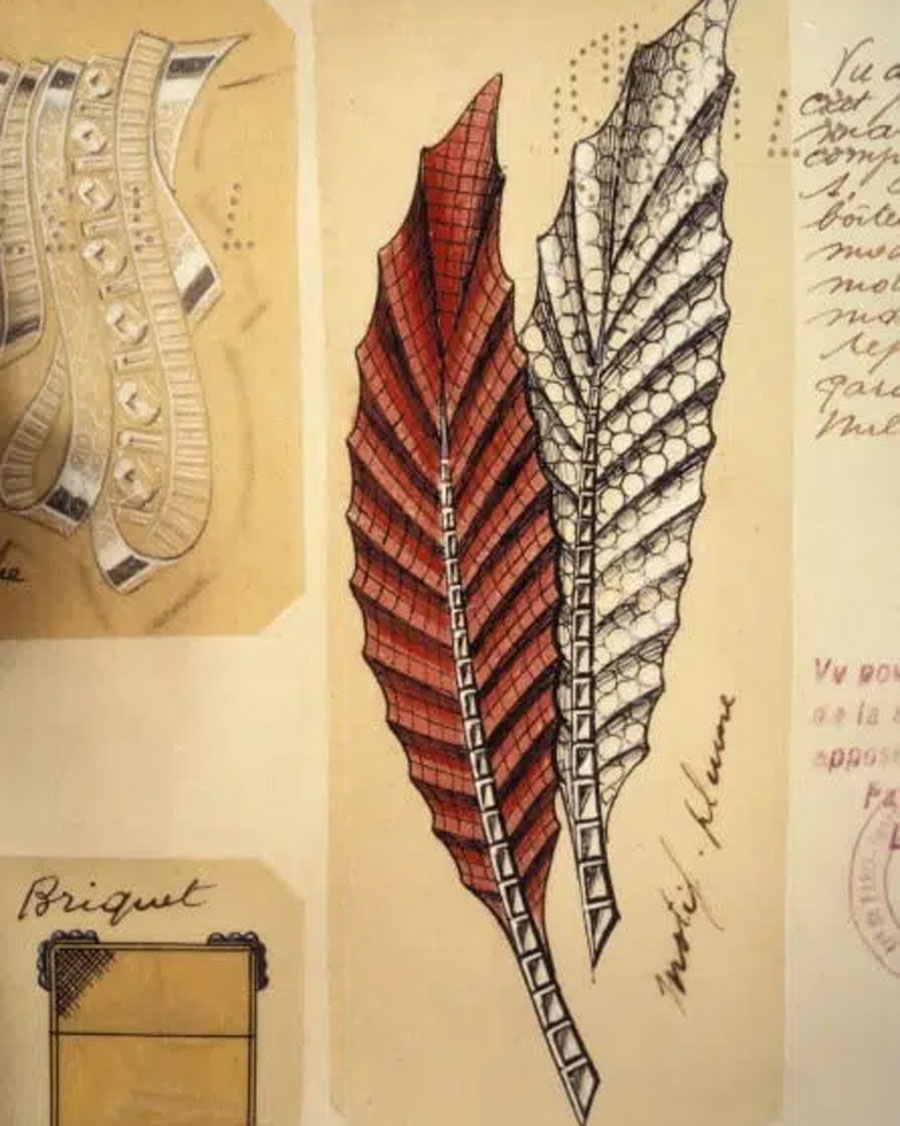

Van Cleef & Arpels Diamond Tiara (Hair Ornament), 1937

A tiara might seem an unlikely commission for a couple who had deliberately stepped away from royal life. Indeed, Wallis Simpson herself famously declared, “A tiara is one thing I will never own.” Yet Edward VIII believed she should have one—provided it was unlike any other.

Rather than a traditional crown, he commissioned an unconventional tiara-like jewel from Van Cleef & Arpels, conceived as an asymmetrical diamond hair ornament. Designed with removable clips, the piece could be worn with varying degrees of prominence, adapting to different occasions and rejecting rigid court conventions. Rendered entirely in natural diamonds, it functioned less as a symbol of rank and more as an expression of individuality, precisely the quality that defined Simpson herself.

Cartier Diamond and Ruby Bracelet, 1938

Originally conceived as a necklace in 1937, this piece was later reimagined by Cartier as a bold Art Deco–style bracelet. Edward presented it to Wallis Simpson on June 3, 1938—their first wedding anniversary—while they were summering on the French Riviera. As he did with much of her jewelry, the duke had it engraved with a deeply personal inscription: “For our first anniversary of June third.”

Set with rubies and diamonds, the bracelet is a clear expression of Wallis’s refusal to embrace a quieter aesthetic. Graphic, confident, and unapologetically bold, it asserted her presence. “She loved color and was unafraid to stand out. Even her use of paste was intentional and strategic. At her presentation at court in 1931 (often incorrectly dated earlier), she wore an imitation aquamarine cross. Even before meeting the duke, jewelry functioned as armour. A way to control how she was read, regardless of means,” Gerrish says.

The bracelet also gains meaning when viewed alongside the earlier ruby jewel Edward gave Wallis in 1936: a Van Cleef & Arpels ruby bracelet inscribed with the words “Hold Tight,” presented during the uncertain period before her divorce was finalized. Read together, the two bracelets trace a narrative arc—from anticipation and endurance to arrival and affirmation—etched quite literally in stone.

Cartier Flamingo Brooch, 1940

The flamingo—arguably one of the most structurally striking and vividly colored birds in nature—proved an inspired motif for this extraordinary brooch, rendered in diamonds, rubies (a particular favorite of Simpson’s), and sapphires. Designed by Cartier in 1940, the piece captures the house’s mastery of movement, color contrast, and sculptural elegance, with the bird’s sinuous form appearing almost animated against the wearer’s clothing.

A gift from Edward VIII, the brooch quickly became one of Wallis’s most recognizable jewels and a signature of her post-abdication style. More than decorative, the flamingo embodied her enduring preference for bold color, exotic imagery, and confident scale.

Cartier Amethyst Bib Necklace, 1947

Cartier created a strikingly wearable work of art with this amethyst bib necklace, designed for Wallis Simpson. Set with diamonds and turquoise, the necklace is anchored by a dramatic heart-shaped amethyst drop at its center. Its bold palette and bib-like silhouette signaled a decisive shift toward postwar exuberance, blending Indian-inspired form with Western gemstone traditions in a way that felt both exotic and modern. The stones were reportedly selected by Edward VIII himself, underscoring the deeply personal nature of the commission.

Cartier Sapphire and Diamond Panther Brooch, 1949

Keeping with Wallis Simpson’s enduring fascination with powerful, majestic cats, no discussion of her jewelry is complete without the Cartier Sapphire and Diamond Panther Brooch. While the panther bracelet is arguably the jewel most synonymous with her name, this brooch further underscores her attachment to the motif. Crafted in platinum and pavé-set with brilliant-cut diamonds, the panther is rendered not in repose but crouched mid-pounce, its body taut with tension and movement. Beneath it rests a spectacular round cabochon star sapphire weighing 152.35 carats.

Editor’s Note: If panthers dominated Wallis’s public jewelry language—symbols of control, power, and self-possession—her private affections were far softer. While she reserved her love of big cats for jewels, her devotion to pugs was entirely real. Wallis and Edward owned several over the years, treating them as constant companions rather than pets.

The dogs traveled with the couple, drank from silver bowls, wore silver collars, and were indulged with every imaginable comfort. In keeping with the Duchess’s famously uncompromising tastes, even the household décor reflected this devotion: the Duke and Duchess slept on pug-monogrammed sheets and surrounded themselves with pug-themed objects. Simpson herself reportedly drafted weekly menus for the dogs—cooked fresh each day—that included ground steak. After Edward’s death, his beloved pug James was said to have been so grief-stricken that he died shortly thereafter.

Van Cleef & Arpels Zip Necklace, 1951

This famous piece is something of an outlier: Wallis Simpson never actually owned a Zip necklace. Yet she is widely credited with conceiving the original idea.

The zipper itself was introduced in 1893 at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago and later refined and manufactured in Hoboken in the early 20th century, most notably through the innovations of Gideon Sundback. By the 1930s, this once-utilitarian fastener had begun to infiltrate high fashion, embraced by designers such as Elsa Schiaparelli. When Wallis encountered the zipper in the early 1930s, she proposed a radical idea: transforming the mechanism into a fully articulated diamond necklace. She brought the concept to her close friend Renée Puissant, then artistic director of Van Cleef & Arpels, asking her to bring the vision to life.

It would take nearly two decades for the idea to be perfected. Introduced in 1951, the Zip Necklace had to function exactly like its industrial counterpart—unzipping and re-zipping seamlessly—an extraordinary feat of craftsmanship that can require up to 1,200 hours to produce a single piece. Rendered in platinum and set with round and baguette-cut diamonds, with interlocking gold teeth concealed within the design, the necklace blurred the boundary between engineering and haute joaillerie.

Although Wallis was never photographed wearing one and apparently never owned a Zip Necklace herself, the concept remains inseparable from her legacy. The diamond Zip Necklace became a signature of the Van Cleef & Arpels collection and continues to appear on red carpets today, worn by the likes of Margot Robbie, Ginnifer Goodwin, and Cate Blanchett—a lasting testament to Wallis’s instinct for transforming the modern into the monumental.

Cartier Diamond and Onyx Panther Bracelet, 1952

This extraordinary Panther Bracelet stands as one of the most emblematic jewels associated with the Duchess of Windsor. Yet the panther motif itself might never have reached such iconic status without the vision of Jeanne Toussaint, the formidable Director of Fine Jewelry at Cartier. Nicknamed La Petite Panthère by Louis Cartier, Toussaint transformed the animal into one of the maison’s most enduring symbols.

While the panther had appeared in Cartier designs as early as 1914, it was under Toussaint’s influence that the motif became inseparable from the house’s identity. Early iterations relied on graphic patterning—onyx and diamonds arranged to mimic the markings of panther skin. Over time, and under her guidance, the design evolved into fully three-dimensional jeweled sculptures, imbued with movement, tension, and sensuality. No wearer embodied that daring evolution more perfectly than Wallis Simpson, whose bold personal style and unapologetic presence made the panther feel not merely ornamental, but inevitable.

“Motifs reinforced this authorship. Big cats signified strength and danger; crosses and inscriptions transformed private devotion into public fact; even her love of pugs, echoing earlier royal precedent, became part of a carefully curated identity. Objects mattered because they carried meaning,” Gerrish says.

It is telling that she later gave Cartier panther earrings to Princess Michael of Kent—the only member of the British royal family to receive jewels from her—in a rare and deliberate gesture of continuity.

Cartier 20th Wedding Anniversary Heart-Shaped Brooch with Diamonds, 1957

This heart-shaped brooch was another significant anniversary gift from Edward VIII to Wallis Simpson, marking twenty years of marriage. Pavé-set with brilliant- and single-cut diamonds, the design centers on a monogram of their intertwined initials—“W” and “E”—picked out in calibré-cut emeralds. Beneath it, the Roman numerals “XX” denote the milestone anniversary, rendered in calibré-cut rubies. “Her heart-shaped jewels, worn repeatedly, reveal emotional expression and the need for continuity in exile,” said Gerrish.

Cartier Emerald and Diamond Necklace, 1960

This necklace proved that one need not be royal to wear royal jewels. While there has long been some ambiguity surrounding its precise origins, the prevailing consensus is that Cartier created the necklace in 1960. The design features five pear-shaped clusters, each centered on a pear-shaped emerald framed by baguette- and marquise-cut diamonds. These front elements are linked to a series of semi-circular sections along the sides and back, set with round- and square-cut diamonds.

The principal emerald weighs 14.61 carats, accompanied by four additional pear-shaped emeralds ranging from 5.82 to 7.82 carats. The stones themselves are believed to have royal provenance: the central emerald is widely thought to have once belonged to Alfonso XIII, who reportedly sold it while in exile during the 1930s. The result is a necklace that merges aristocratic history with Wallis Simpson’s distinctly modern authority.

How Wallis Simpson Collaborated with Cartier and Van Cleef

Like many women who built extraordinary jewelry collections during this period, Wallis Simpson was not a decorative client; she was a creative collaborator. Nowhere is this more evident than in her relationship with Cartier under Jeanne Toussaint (universally known as “Pan Pan”). “Their partnership succeeded because it was built on recognition. Both women were outsiders who had fought their way into positions of authority, and both had challenges in a male-dominated world of set rules and power. Even love. Both understood jewelry as a vehicle for power, symbolism, and self-authorship rather than ornament,” Gerrish says.

Gerrish notes that Toussaint did not simply design for Wallis; she translated Wallis’s identity into form. Toussaint acquired her nickname “Pan Pan” after a 1913 safari, during which she encountered panthers in the wild. She often dressed in leopard skins, decorated her apartment with panther imagery, and collected panther jewels herself. “When Wallis embraced the panther, it was not branding. It was alignment. Toussaint’s Paris apartment at Place d’Iéna became a key meeting point for this creative world.”

That world included Cecil Beaton, who photographed both women and understood their visual intelligence. He famously remarked, “This apartment is like a secret that few are privileged to share.” The observation captures the atmosphere precisely: rarefied, controlled, and intensely curated—much like Wallis’s jewelry itself.

The collaboration culminated in 1952 with the diamond and onyx panther bracelet, a technical and conceptual breakthrough, says Gerrish. “Unlike traditional rigid bracelets, the panther moves, flexes, and wraps around the wrist like a living creature. This was not a stock jewel adapted to a famous client; it was a leap in engineering and imagination, made possible because Wallis trusted Toussaint’s instincts and because Toussaint trusted Wallis’s appetite for strength, danger, and scale,” she says.

Wallis Simpson also worked extensively with Van Cleef & Arpels on a number of remarkable pieces, as seen above. “She was the design lead dream for a jeweler, and an ambassador of modern jewels of the time. With Harry Winston, Seaman Schepps, Suzanne Belperron, and Tony Duquette, she encouraged boldness in color, gold, and scale, helping to normalize semi-precious stones and yellow gold for evening wear.”

That is why the panther is the perfect symbol of how Simpson collaborated. “It was not designed for her so much as designed with her. The meeting point between Toussaint’s inner mythology and Wallis Simpson’s public identity. Few clients have ever left such a clear creative fingerprint on a major jewelry house,” said Gerrish. “Ultimately, Wallis used jewelry to do what a monarchy could not do for her.”

Gerrish also noted that Wallis Simpson remained deeply involved with her jewels long after their creation. She consistently reset pieces—such as her emerald engagement ring—reinterpreted designs, and re-wore them across decades. “Nothing was static; everything was lived with. Jewelry marked time, endurance, and continuity.”

The 1987 Sotheby’s Sale That Cemented Wallis Simpson’s Legacy

When a jewelry collection has been dubbed the “alternative Crown Jewels,” strong auction results are almost guaranteed. “Strong,” however, barely captures the impact of the 1987 sale of Wallis Simpson’s jewels. Held a year after her death, the landmark auction took place at Sotheby’s, staged in specially constructed tents outside the Beau-Rivage Hotel on the shores of Lake Geneva (the Duke of Windsor had died in 1972). In total, 214 pieces realized approximately $53 million—setting a world record at the time for the highest-grossing single-owner jewelry sale ever conducted.

Interest in her jewels has only intensified in the decades since. In 2021, her ruby and diamond Cartier bracelet sold for approximately $2.15 million at auction, reaffirming the enduring demand for pieces associated with her story. Often described as the “romance of the century,” the fascination surrounding Wallis and Edward’s legacy shows no sign of fading. That intrigue continues to extend beyond the auction room: a biographical film titled The Bitter End, written by Emerald Fennell, has been announced and is set to explore Wallis’s later years in Paris, further cementing her place in cultural—and jewelry—history.

What Wallis Simpson’s Jewelry Ultimately Accomplished

Wallis Simpson’s jewelry collection was remarkable for its artistry, technical innovation, and craftsmanship. But unlike that of many of her contemporaries, her jewels stood for something. They made exile visible, deliberate, and powerful—transforming displacement into a form of control.

Once she became ‘that woman,’ a figure defined in the public imagination by scandal, exile, and exclusion, Wallis could no longer depend on institutions, titles, or court structures to confer legitimacy. Popular portrayals have often distorted this moment (cough Netflix’s The Crown). “She did not stand behind Edward VIII, urging abdication; on the contrary, when she was in France with only a modest telephone line, she neither anticipated nor desired it. Simplistic narratives of ambition or manipulation collapse under scrutiny,” says Gerrish.

Deprived of institutional validation, Wallis Simpson was forced to author her own legitimacy—and she did so through the language of jewelry. Her singular style, discerning eye, and unwavering confidence remained constant, guiding her through some of the most difficult chapters of her life.

“This need for authorship and control never left her. Even at the end of her life, she extended it to her own body, allowing only doctors to see her. The same instinct that governed her jewel-self-definition, privacy, and authorship governed her final years. Ultimately, Wallis used jewelry to do what monarchy could not do for her: to construct legitimacy, to project power in exile, and to turn scrutiny into spectacle. Her jewels were not decorations. They were identity made visible,” said Gerrish.