Tracing The Evolution Of The Maang Tikka

From a bridal staple to a fashion statement, the maang tikka has great significance in Indian culture, especially when worn by the bride.

Jewellery in India can never be viewed through an isolated lens. A country that has honed its traditional adornment for centuries, any given piece’s significance goes well beyond just the sartorial. In the case of the maang tikka, a centuries-old traditional Indian headpiece, the provenance is in fact spiritual.

According to the Vedas, the centre of the forehead is home to the Ajna Chakra or the third eye, the seat of concealed wisdom. This is exactly where the maang tikka (‘maang’ meaning middle parting and ‘tikka’ meaning ornament) sits—it represents the ability to control emotions, and tap into one’s power of concentration. Hence, the maang tikka is said to bestow the wearer with will and wisdom to embrace their journey in life. Traditionally, the chakra is represented by two petals where the half-male and half-female androgynous deity Ardhanarishvara resides, thereby serving as a metaphor for the holy union of the male and female spiritually, physically and emotionally.

Another legend surrounding the origin of the maang tikka goes back to ancient India when a king victorious in war, would smear the blood of his enemy on the queen’s forehead, including the middle parting of her hair. Therein was born the tradition of the sindoor, a sacred symbol of her husband’s well being for Hindu brides. Even today, during the wedding ceremony, the groom lifts the bride’s maang tikka to apply sindoor (vermillion powder) and places it back—symbolising the bride’s sindoor being protected from the evil eye. These traditions make the maang tikka a significant component of the solah shringar (or 16 bridal ornaments) that a Hindu bride typically adorns herself with on her wedding day. “The maang tikka is worn to protect the bride from the evil eye and negative energy. But most essentially, it signifies the union between the bride and the groom,” explains Abhishek Raniwala, co-founder of heritage jewellery brand Raniwala 1881. This is why the maang tikka has been retained in the traditional bridal garb as a fitting symbol of holy matrimony over the years.

From flowers to natural diamonds: the making of the maang tikka

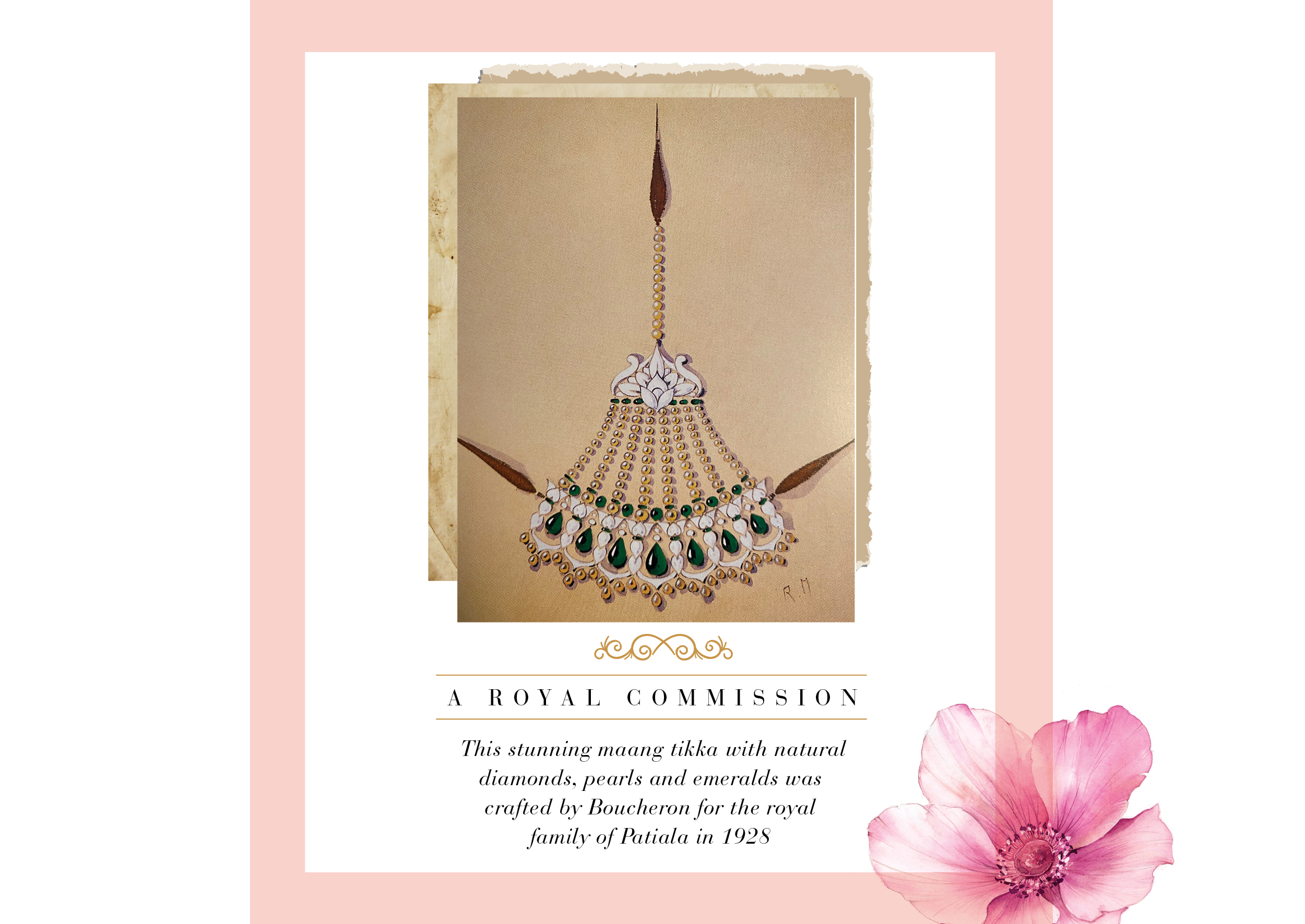

Worn by communities across the country, every region boasts its signature take on this head piece—Rajputs of Rajasthan wear a gold and polki drop-shaped borla; Muslim brides favour a more elaborate chandelier-style jhoomar or passa typically made of kundan, pearls and gemstones, worn on the side of the head; and brides in Punjab tend to opt for moon-shaped chand bali-esque tikkas. Noted art historian and curator Amin Jaffer says, “Like much traditional jewellery, I imagine that the form was first known in the form of flowers worn symbolically on the forehead. Over time, petals and blooms were translated into gold and gemstones, often imitating floral forms.” Jaffer is drawn to Indian jewellery from the Art Deco period that fuse geometry and light platinum settings with traditional forms. “I would say that the forehead ornaments, nose rings and armbands made by Cartier and Boucheron for Indian clients are among my favourite,” citing an elaborate natural diamond, pearl and emerald design by Boucheron (pictured here) from 1928, a commission for the royal family of Patiala.

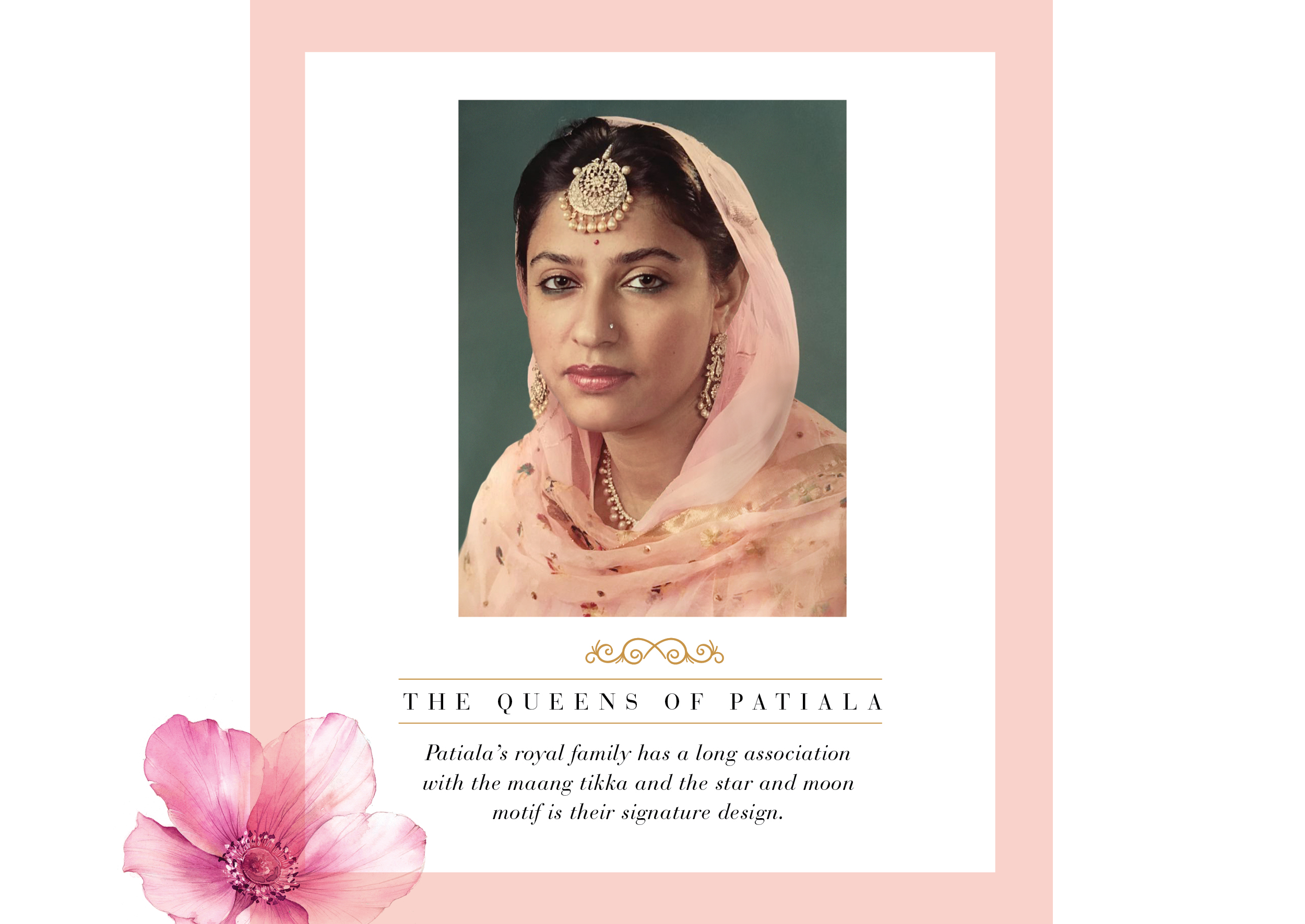

Rani Vinita Singh of Patiala attests to the importance of this piece of jewellery as a part of their traditional royal garb. “Patiala has a long association with it. We wear the maang tikka regularly; for every important celebration and occasion—be it family weddings, karva chauth, haryali teej or lohri. Along with the nath, it is an important marker for a married woman.” The star and moon motif is the royal family’s signature design when it comes to the tikka, always crafted from mixed-shaped natural diamonds. Since they are always made to match a suite, the natural diamonds could also be combined with gemstones and pearls.” Even though the universal symbolism associated with the maang tikka remains consistent for brides across the country, the indigenous variations add further character to its narrative and evolution.

Then and now: The maang tikka today

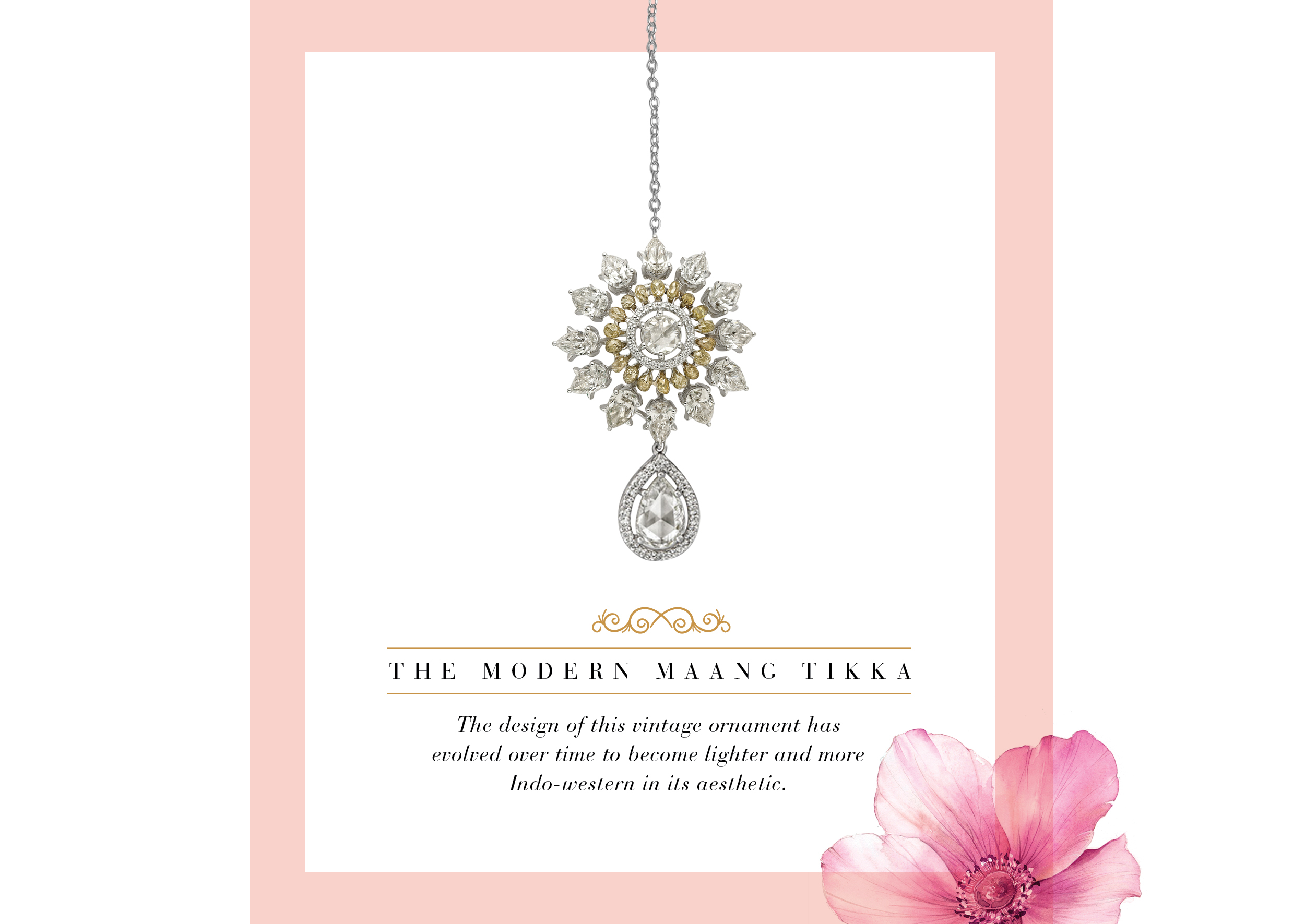

The maang tikka has transcended well beyond bridal and wedding wardrobes today. In fact, global influencer Kim Kardashian has worn this innately Indian accessory twice—once with a white sheath gown and another time with a grey co-ord set. Raniwala adds that the traditional maang tikka’s design and size too have both evolved over time. “Earlier families preferred bigger tikkas. With changing trends, brides are more inclined towards chic pieces now.” The result is a juxtaposition of real diamonds with uncut variants and gemstones.

“Traditionally, maang tikkas were worn only by the bride and other married women. But women today are breaking the traditional mould and embracing it as a fashion statement with a contemporary edge.”

Explains Karan Vaidya, Rose, VP Marketing and Retail Operations of diamond jewellery brand Rose.

Rose, which has been designing maang tikkas for over 35 years, is known to give this vintage accessory a more present-day update.

“The current preference is for designs in natural diamonds that blur the line between western and ethnic. We work with fancy-shaped diamonds clustered together to form contemporary asymmetrical flowers. In its most elementary form, our designs have a simple chain ending in an embellished pendant.”

Even when working with crescent-shaped jadau maang tikkas reminiscent of what yesteryear maharanis wore, they married uncut diamonds with natural brilliant-cut diamonds to create showstoppers.

While it’s always fascinating to study the history of a bejewelled staple, it’s more relevant to look at how it’s being reinvented to reflect the mindset. In the case of the maang tikka, it epitomises centuries of customs and philosophical symbolism to emerge as a merger of the old with the new—a piece of the past with an eye on the future.