Head to Toe in Natural

Diamond Jewellery

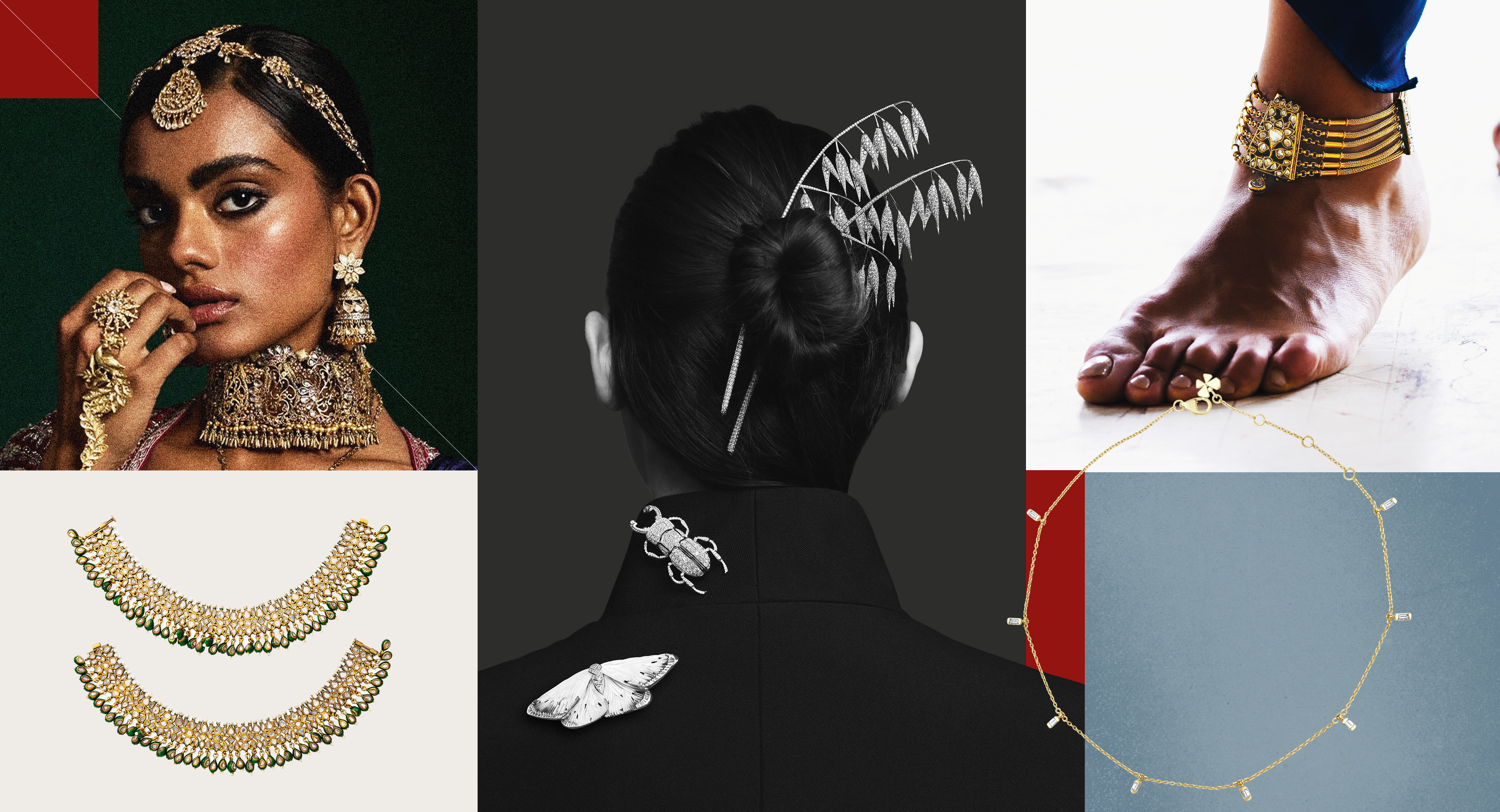

Once reserved for ceremony, embellishment for the hair and feet is making a considered return. Set in natural diamonds, these jewellery placements are redefining how and where we wear brilliance.

For centuries, jewellery has graced the body’s periphery — the brow, the braid, the ankle. They carry with it an unspoken allure, drawing the eyes to these liminal zones, sites often emotionally and sensually charged. In India and across the Middle East and North Africa, these placements held ritual, rhythm, and meaning. Today, they are reappearing through natural diamonds, as designers revisit these sites of adornment with clarity, subtlety, and a renewed sense of relevance. These forms invite a more private kind of attention.

An anklet worn with sandals, a jewel nestled in the braid shifts focus to parts of the self often left bare. Without relying on scale or spectacle, they speak through articulation, proportion, and nearness.

Where It Began

To better understand these traditions, it’s worth distinguishing the many styles they took and their evolution over time — from the Mughal courts of the 16th century, where royal figures wore diamond-studded sarpech and maang tikkas, to the Chola dynasty in South India, known for intricate temple jewellery made of gold and uncut stones.

The maang tikka is perhaps the most widely recognised, resting on the centre parting and forehead, often circular or teardrop in shape. In Rajasthan, its variation is the borla or bor, a spherical ornament worn in the centre of the forehead, typically anchored by a fine chain. The matha patti, also seen across North India, expands on the tika’s verticality by extending decorative bands along the hairline, offering both visual balance and symbolic enclosure. It is part of the bridal solah shringar — the sixteen adornments — and evolved to frame the face with symmetry and structure.

In Tamil Nadu, its counterpart is the nethi chutti, which may be single or multi-stranded and anchored more elaborately with floral and sun-moon motifs (suryachandra billai). The jadai nagam refers to snake-shaped braid pieces worn along the length of the hair, typically for weddings or temple festivities. These are often accompanied by round decorative discs known as billai, each element reinforcing a narrative of continuity, protection, and grace.

For the feet, the payal is the standard anklet, traditionally made of silver, a metal associated with grounding energy. The gajje in Karnataka, by contrast, is more rigid and architectural, frequently worn during ceremonial dances. Chilanka, often used in classical dance forms like Mohiniyattam and Bharatanatyam, incorporates bells to heighten rhythmic presence. The bichua (toe ring) is closely tied to marital status in many Hindu communities, worn as part of a bride’s adornment but often retained as an everyday marker of transition.

These regional variations highlight not only design specificity but also the performative and symbolic intent behind each piece. Jewellery, in this context, was a vocabulary encoding status, region, phase of life, and devotion.

One of the most striking early visual records of Indian foot jewellery is a black-and-white photograph titled “Foot of an Indian Princess,” from India / The Passion Play by John L. Stoddard (1897–1900). It depicts a South Indian woman’s foot layered with silver anklets — a design language mirrored today in contemporary expressions to reinterpret the silhouette with detailing and material sophistication, often bringing natural diamonds into forms traditionally reserved for gold and silver. The result is pieces that combine rigid and flexible elements — textured coils, bells, charms, and repoussé work — designed to create both sound and spectacle as the wearer moves.

“The feet carried rhythm. The head held structure. Together, they traced a line of adornment that moved with the body, not against it.“

From the jadai nagam and billai to the maang tikka, from suryachandra billai to nethi chutti, the forehead has long been a place of focus and symbolic weight. Over time, particularly through the mid-to-late 20th century, these adornments saw a decline in everyday use, often relegated to bridal or ceremonial contexts as Western aesthetics dominated. Yet even as their visibility waned, their symbolism — of passage, heritage, and feminine power — endured in heirlooms and regional practices, waiting. Similarly, space close to the earth held their own vocabulary: gajje, chilanka, payal, and bichua among them. These pieces marked entry into a new stage of life, signalled identity, and reinforced the wearer’s place within a larger socio-economic framework.

Contemporary Expressions

Natural diamonds bring durability and restraint to these revived iterations. Designers working with them today are stripping back excess to let structure, composition, and emotion do the work.

At The Line, Natasha Khurana’s pieces lean into architecture. She notes, “I designed our Mini Bar Diamond Anklet (the bar an essential part of The Line’s design language) to carry an earthy beauty, that’s both romantic and utilitarian. You can wear it to swim, sleep in it, pair it with any footwear, basically wear it all the time, no fussing involved. All the while it twinkles its diamond enchantments to the viewer.”

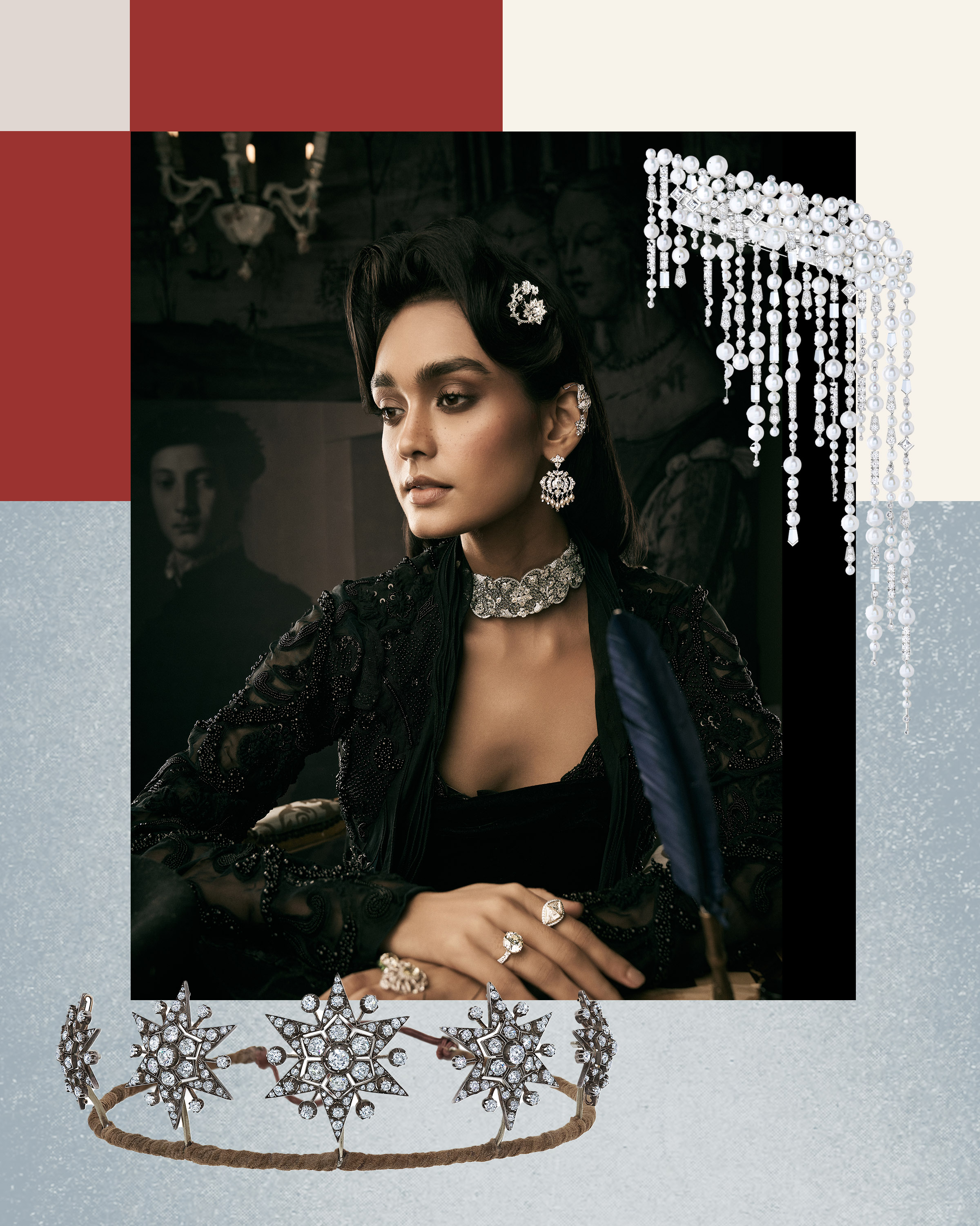

Birdhichand Ghanshyamdas, one of Jaipur’s most storied houses, created a choti for Isha Ambani — a diamond-encrusted braid ornament that fuses traditional motifs with craftsmanship. It draws from heritage to create something distinctly contemporary, offering a ceremonial piece that still feels of this moment. It is an emblem of how legacy design houses continue to evolve historical methods without diluting their intent.

Kantilal Chotalal moves across registers, from intimate, gem-laced hair pins to sculptural, nature-inspired creations like a diamond-encrusted butterfly brooch.

Internationally, brands like Boucheron have turned to sculptural hair jewellery, folded gold and structured latticework shaped from platinum and natural diamonds. These are abstract, forward-facing designs that signal a broader shift: adornment not as inheritance, but as attitude.

A Material Meant to Move

Adornments, when placed at the body’s edge, become companions to memory and ritual.

“And natural diamonds, unlike other stones, are both discreet and definitive in how they reflect those movements. It is this tension, between delicacy and endurance, that gives natural diamonds their power.“

As Jaipur-based Sunita Shekhawat observes, “in natural diamond jewellery, there is always a certain sense of purity and eternity that flows through it.”

In a 19th-century South Indian portrait attributed to Sekhara Warrier, a young woman sits poised in a “love chair,” her head richly adorned with traditional nettichutti and diamond-set Victorian star and crescent motifs — a meeting of Indian and Edwardian aesthetics. Over a century later, Deepika Padukone, at the 2017 Met Gala, wore a vintage Fred Leighton diamond star headband with similar brilliance and restraint. The similarity isn’t incidental, it’s evidence of how natural diamond head ornaments have always lent themselves to reinterpretation, spanning royalty, red carpets, and now bridal trendboards.

Shekhawat’s own approach is different but equally precise. Her choti and hair combs use traditional enamel techniques and uncut diamonds, refined into wearable heirlooms. “With traditional forms like the choti or head comb, I focus on preserving their cultural essence with a thought toward design for the modern woman. I simplify the silhouettes, use soft enamel tones, and balance uncut diamonds with delicate meenakari work. The aim is to create something timeless and wearable; in essence, something that represents the present with the past.”

The Return

These ornaments may once have symbolised power, ritual, or romance. Today, in an era of hyper-visibility, they offer a return to intimacy. Historically, such pieces were described as “more for ornament than convenience.” That still holds. But today, they also reflect choice — a move toward adornment that is attuned to personal rhythm.

As Khurana puts it, “bringing the beauty of natural gems into the fold of the everyday.”

They’re no longer worn only because tradition dictates it — they can reflect memory, identity, or simply the pleasure of ornament.

And that’s what makes this moment interesting. It’s not about revival. It’s about re-alignment and reimagining how and where natural diamonds speak to identity today.

Perhaps tomorrow’s heirlooms will sit not on fingers or necks, but along a braid, or just above the heel, carrying forward the brilliance, emotion and continuity this material was always meant to hold.