Diamonds and India – A Romance for the Ages

Diamonds have captured the imagination of royalty through the centuries. They continue to beguile and fascinate women across all ages. Sathya Saran traces the gem’s journey from Mughal courts to its modern interpretations as an aspirational heirloom.

Diamonds have captured the imagination of royalty through the centuries. They continue to beguile and fascinate women across all ages. Sathya Saran traces the gem’s journey from Mughal courts to its modern interpretations as an aspirational heirloom.

Almost as mesmeric and perennial in their sparkle as the stars in the sky, these are stars that nature crafts deep within the earth. Working in her mysterious way to transform base matter into a diamond with the same precision with which she helps a caterpillar emerge as a butterfly.

But unlike the butterfly which lives for a brief day, a natural diamond never loses its brilliance. Making it a gem that the powerful loved, seeing as they did in its hardness a symbol of their own invincibility; and in its brightness a reflection of their power and light. Today, the diamond continues as a signifier of individual achievement.

Lighting up Mughal courts

Indian kings have always found a special place for diamonds. Sir Thomas Roe, Ambassador to the Mughal court, notes with wonder in his manuscript, titled “Embassy of Sir Thomas Roe to the court of the Great Mogul, 1615-1619 as narrated in his journal and correspondence” that Jahangir was “laden with diamonds.” Many museum exhibits dating back to as early as 1625, show diamonds shining from Indian turban ornaments, and decorating the jade handles of swords and daggers that belonged to Indian kings or nobles.

Abdul Hamid Lahori who witnessed the court of Shah Jahan, speaks of the natural diamonds that dominated the gem-encrusted Peacock Throne. Lahori’s account includes the 186-carat Koh-i-Noor diamond, the Akbar Shah diamond weighing 95 carats, as well as the 88.77-carat Shah diamond and the 83-carat Jahangir diamond. The only other gem he notes is the exceptionally large Timur Ruby, which at 352.50 carats was the third-largest Balas ruby in the world.

A dagger hilt set with a mythical lion-headed beast, possibly from Tanjore or Mysore, was bedecked mainly with Kundan set diamonds, alongside rubies and emeralds.

Favoured Embellishment

The mines of Golconda yielded their beauty, and royal houses in Hyderabad had gold betel leaf boxes that were decorated with diamonds and enamelled panels, as well as diamond studded gold bowls with matching stands, which were possibly from the late 1700s. And of course, the diamonds in the Nizams’ family collections could have bought the rest of India!

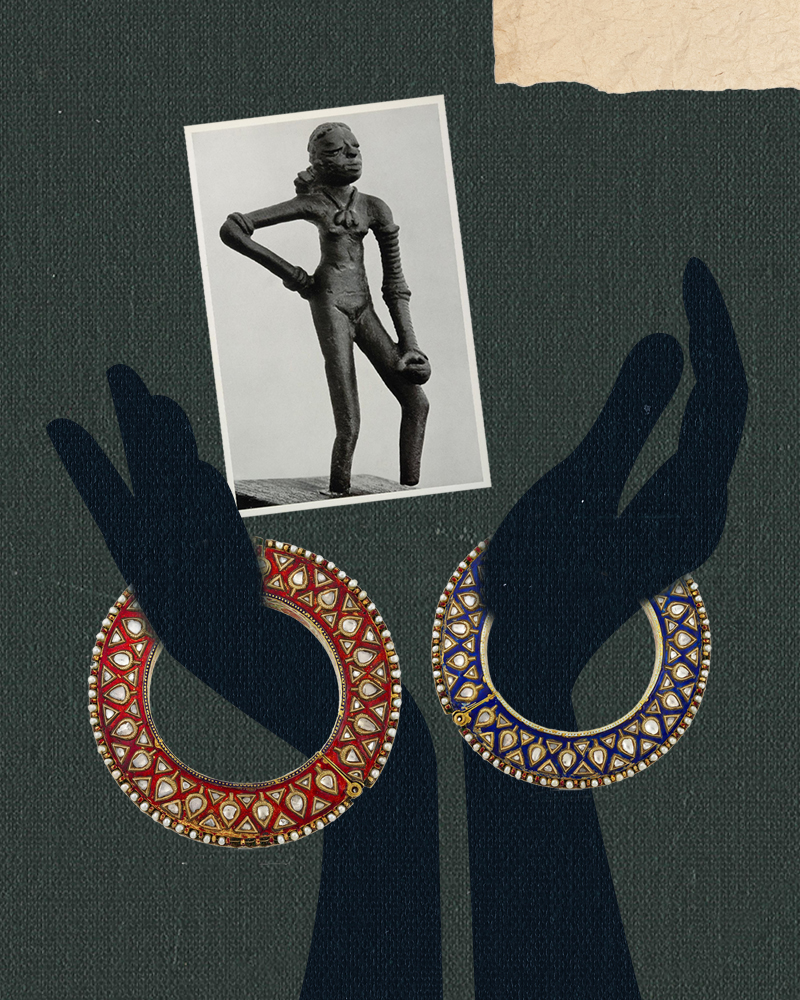

Table cut and round Kundan diamonds, combined with Cabochon rubies and emeralds were used to decorate Tipu Sultan’s throne, and by the 1800s, natural diamonds were indispensable and embellished every royal object from ankush to anklets. And historians write about Lord Clive, who brought back from his sojourn in India, two impeccably cut pear-shaped diamonds presented to him by the Nawab of Arcot. The ‘Arcot diamonds’ were, in turn, presented by Clive to Queen Charlotte, who wore the 1,20,000 pound gift in her ears. By the 20th century, Indian kings were patronising European jewellers like Cartier, Van Cleef & Arpels and Harry Winston, influencing their creations with Indian motifs.

Modern Marvels

Over the centuries, many treasures created by these houses for royalty have disappeared.

The story of the Patiala necklace that Cartier created for Bhupinder Singh of Patiala in 1911, with 2,930 diamonds that centred around the 234.65 carat De Beers diamond is well known. While the cause of the necklace’s disappearance in 1928 was never discovered, the pieces of it found by a Cartier associate in a second-hand jewellery store were bought by the group to help reconstruct the original with imitation stones.

Also, part of royal history is the large diamond buckle that Shatrujit ‘Tikka’ Singh of Kapurthala remembers seeing, in photographs of his grandfather, at public receptions. According to him, “Mahajal, one of the world’s top ten diamonds was a cushion cut yellow diamond of 139.38 carats, procured in the 1730s when Nadir Shah was sacking Delhi and we were sacking him. It disappeared during the confusion of the Partition. Never to be seen afterwards. The story is it was cut into smaller shapes to suit changing tastes.”

Every royal family has a diamond story. Nawab Kazim Ali Khan of Rampur while remembering a tiara and a crown of incomparable diamonds, says: “Though our family was partial to Basra pearls and had baskets full of them”.

The aspiration to own and wear natural diamonds today continues to dwell in most Indian hearts, as much due to its romantic association with royalty and the past, as the stone’s own allure.

A Personal Story

My own fascination for natural diamonds which I once thought enjoyed an overrated status, started while on a visit home to Madras for a wedding. As was the custom, my grand aunt summoned the diamond merchant so that diamonds, a mandatory part of every trousseau, could be selected for the bride-to-be’s jewellery.

The diamond merchant came to the house in his starched white kurta and dhoti, and produced tiny packets of eggshell white and sky blue tissue from his inner breast pocket. I had begged to watch, and as he unwrapped each packet to reveal the glittering stones nestling within, I was hopelessly smitten. More so, when I learnt how each diamond had suffered greatly from heat and pressure through centuries of its creation. To me, the intense suffering could only result in something pure and unique.

I remember when it was time for me to choose my jewellery, my diamond earrings, in the shape of a horseshoe, were not made of newly bought stones. Instead, my mother prized out half of the pure blue diamonds that formed the centrepiece of her gold waistband. I sat with her at the jewellers and watched eagle-eyed as he reset them as my earrings.

They flashed with new brilliance in their new avatar and matched with a pendant that I wore threaded on a gold collar, made me feel like a queen.

When years later, I held up my earrings to my tiny granddaughter as a present to her, on her first birthday, her eyes caught the sparkle of light in the stones. She lifted her tiny hands to catch the light.

It was a gesture symbolic of the lure of the gem. Its pure ray had enchanted past generations. As it would enthrall the generations to come. Indeed, a gem whose enchantment lasts forever.