Chameleon Diamonds: The Definition of Ever-Changing Beauty

Mike Breeding of the Gemological Institute of America (GIA) explains why the chameleon diamond is such a remarkable gem.

Gemological Institute of America

|

To most consumers, diamonds are prized and lauded for their lack of color; the finest and largest colorless diamonds are the epitome of all that is amazing and majestic in nature. When these stones are free of measurable impurities (termed “type IIa”), they achieve the pinnacle of gemstone beauty and rarity. However, as one starts to learn about the science of color in diamonds, it quickly becomes apparent that “pure” and “impurity-free” may not always be the way to go. Especially when it comes to chameleon diamonds.

Read More: The Science of Colored Diamonds

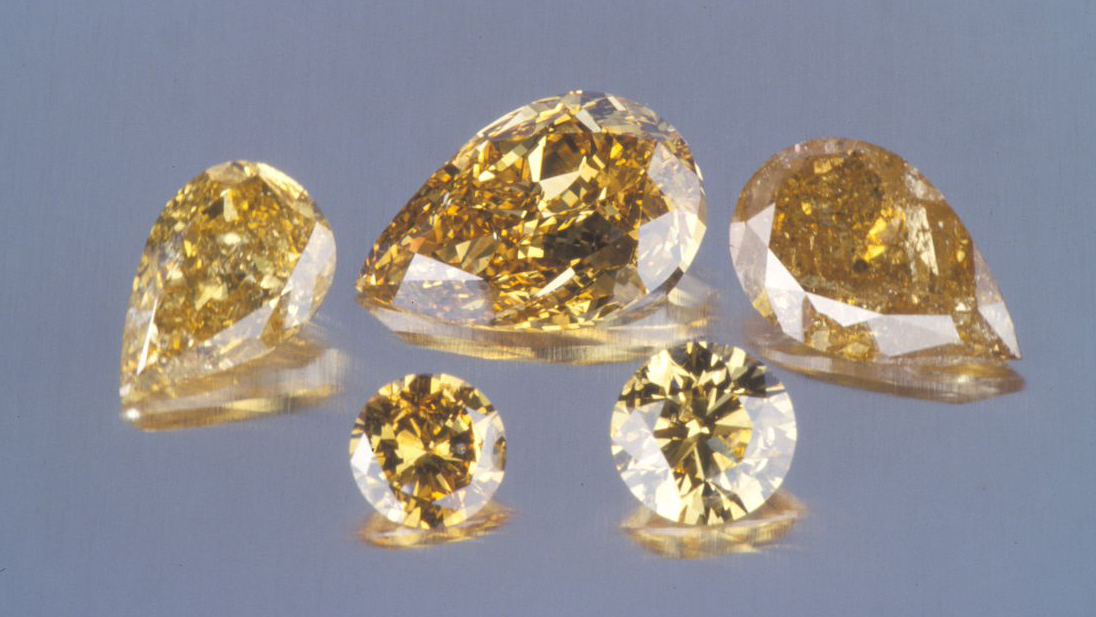

It’s worth noting that the rarest of natural diamonds are those with the deepest and brightest hues—think: blue, red, green and orange—, a product of extremely uncommon and unique conditions within the Earth that allow for the “perfect” combination of impurities to occur.. Representing less than a tenth of a percent of all diamonds, such fancy colored stones are by far the most valuable gems that exist and have sold at auction for as much as $4 million per carat. (In 2015, Sotheby’s sold the 12.03 carat Blue Moon of Josephine, a fancy vivid blue diamond for $48.4 million.) One group of fancy color diamonds, however, is not always content to exist as a single color. Chameleon diamonds, much like their namesake animals, can temporarily change color in response to their environmental conditions (left). While they don’t usually have especially vibrant hues or blend in with their backgrounds, chameleon diamonds go from a greenish color to a yellow or orange color when gently heated (don’t try this at home) or removed from light for an extended period of time. Upon cooling or light exposure, they revert to their original greenish hues within seconds (right). These unique diamonds occupy a special niche among diamond collectors.

What is a chameleon diamond?

While many diamonds may temporarily change color to some extent, chameleon diamonds represent the specific group of stones that tend to have a greenish color component, phosphorescence to shortwave ultraviolet light (meaning they continue to glow after the UV light is off) and the aforementioned temporary color change; to get a “chameleon” comment on a GIA report for a colored diamond, a stone must exhibit all three of those distinctive characteristics. Chameleon diamonds usually have fancy colors ranging from grayish yellow-green to brownish greenish yellow and occur as faceted stones weighing up to about two carats. The largest reported chameleon diamond is the Chopard Chameleon Diamond, weighing in at over 32 carats (below).

There are a number of other interesting properties of these color changing diamonds. All chameleon diamonds are type Ia, meaning that they have nitrogen impurities. Most of them are dominated by aggregated pairs of nitrogen atoms (type IaA) in the atomic structure. Chameleon diamonds also have broad absorption bands at ~480 nm and ~750-800 nm in the visible absorption spectrum, which combine to give them a greenish color appearance. The nature of these two absorption bands is not well understood, but the 480 nm band has been linked by some researchers to oxygen atoms in diamond and the 750-800 nm band appears to be related to hydrogen or nickel impurities. Infrared absorption spectra confirm the presence of hydrogen atoms in these stones and chemical analysis and photoluminescence have documented that most chameleon diamonds also contain measurable amounts of nickel impurities.

How and why do chameleon diamonds change color?

Why chameleon diamonds change color is actually quite complex and one of the continuing mysteries for diamond scientists. What we do know is that the combination of absorptions that cause greenish color (480 nm and 750-800 nm bands) must change in some way to provide for the yellow color that follows heating or extended removal from light. Some researchers have suggested that under these conditions, the 750-800 nm broadband temporarily reduces in intensity to produce yellow color. It’s possible that these somewhat conflicting observations may arise from the mixed nature of most chameleon diamonds.

A hodgepodge of diamond growth?

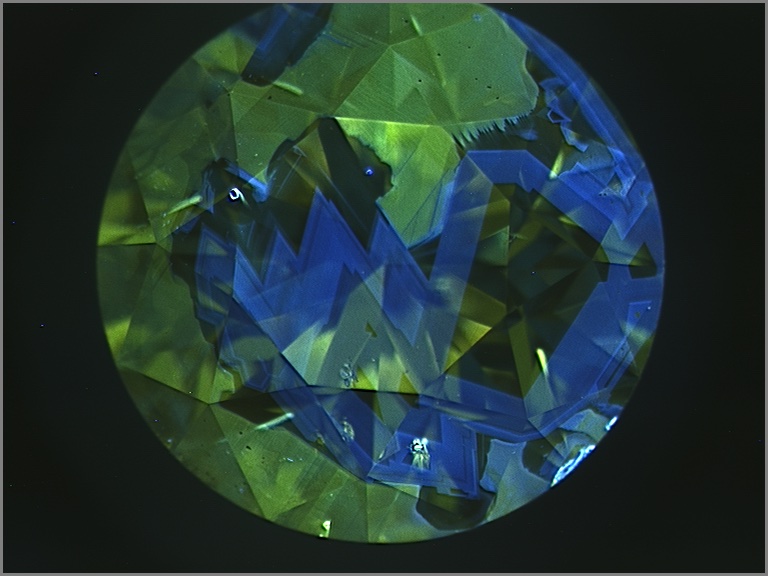

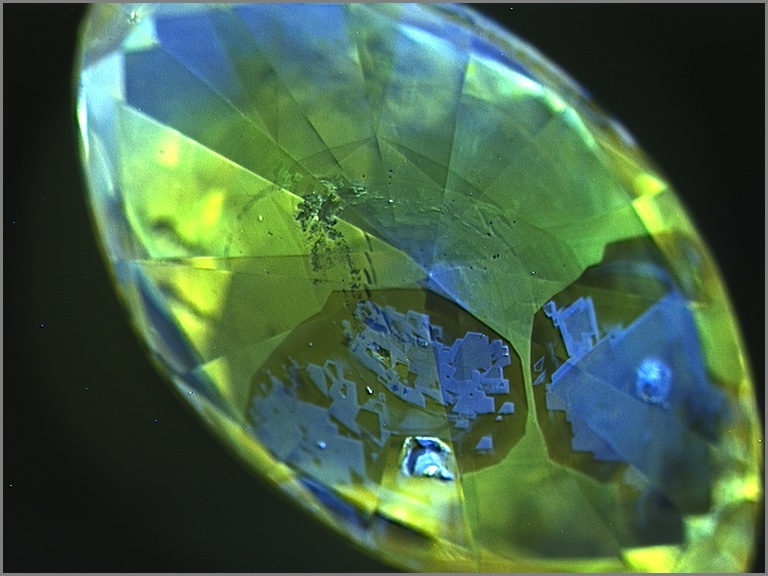

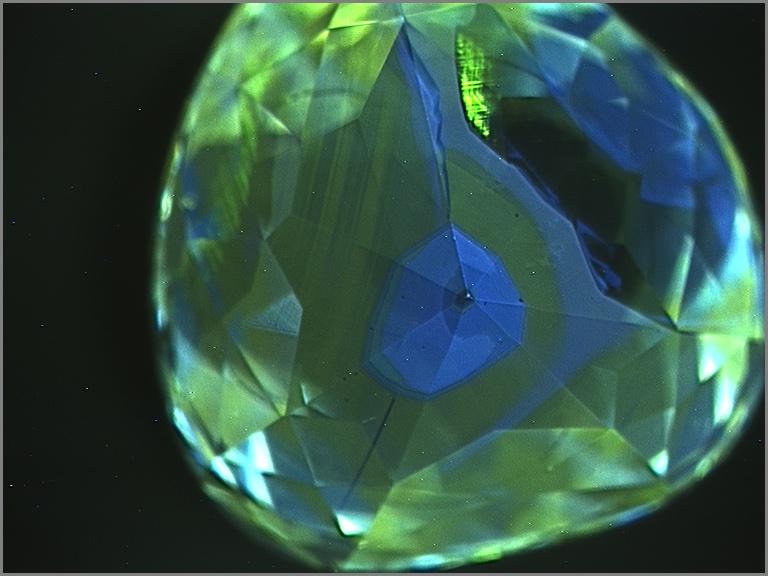

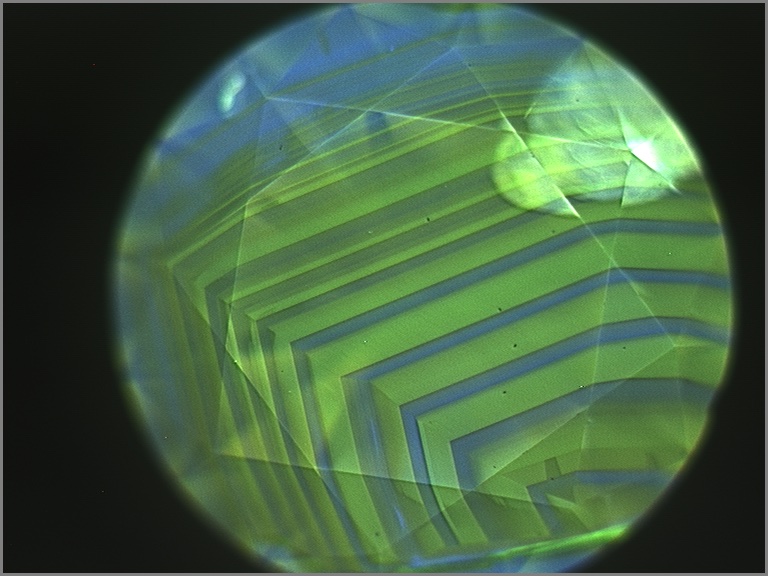

Upon closer examination, most chameleon diamonds show evidence of irregular growth and zonation. These differences are best revealed when examining the stone’s fluorescence under very high energy ultraviolet light. Under these conditions, distinct details of a diamond’s internal structure can be seen by patterns in the fluorescence produced by the distribution of different atomic impurities or imperfections. Chameleon diamonds tend to show some growth regions that fluoresce greenish yellow and others that are inert or fluoresce blue (below). The boundaries between these regions can be regular and oscillatory, or very irregular and jagged, suggesting clear changes in the growth environment of a chameleon diamond. Using carefully oriented spectroscopic analysis, it becomes clear that the greenish yellow fluorescent zones are dominated by 480 nm bands and the inert or blue zones are hydrogen-rich with 750-800 nm bands. Although the amount of each type of growth zone tends to be different from stone to stone, the heterogeneity is almost always present. The co-occurrence of these two zones and the association of each zone with an important absorption band strongly suggests that the very existence of chameleon diamonds and their fascinating color change is a product of a constantly changing geological growth environment.

Chameleon diamonds are revered by many diamond connoisseurs because of their unique abilities and their unrivaled talent to reveal that a special type of beauty can emerge from chaos.