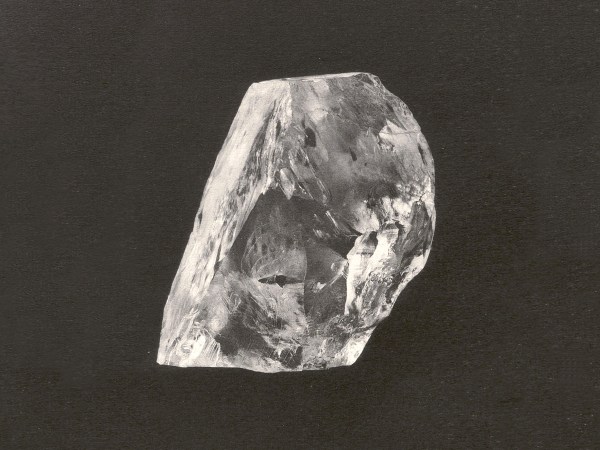

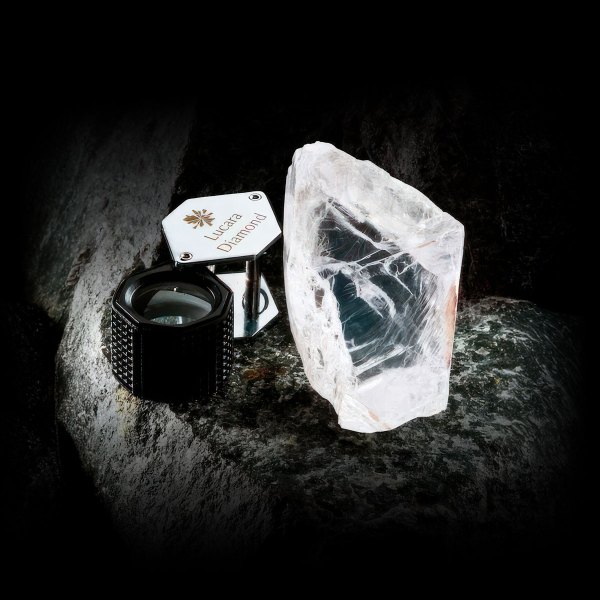

Lesedi La Rona Diamond, rough. Credit: Lucara Diamond

Diamond Report Series

Record-Breaking Diamonds

Record-Breaking Diamonds, the latest in NDC’s Diamond Reports series, explains how advances in technology are fuelling an unprecedented run of spectacular diamond discoveries.

To date, only four diamonds (two gem-quality, one near-gem and one carbonado diamond) exceeding 2,000 carats have ever been discovered – and two of those have emerged in the last two years.

Published: December 15, 2025

Large diamonds are geological outliers – extreme rarities formed deep within the Earth.

Only a handful in history have exceeded 1,000 carats, and each discovery has reshaped what we know about diamond formation, mining and craftsmanship.

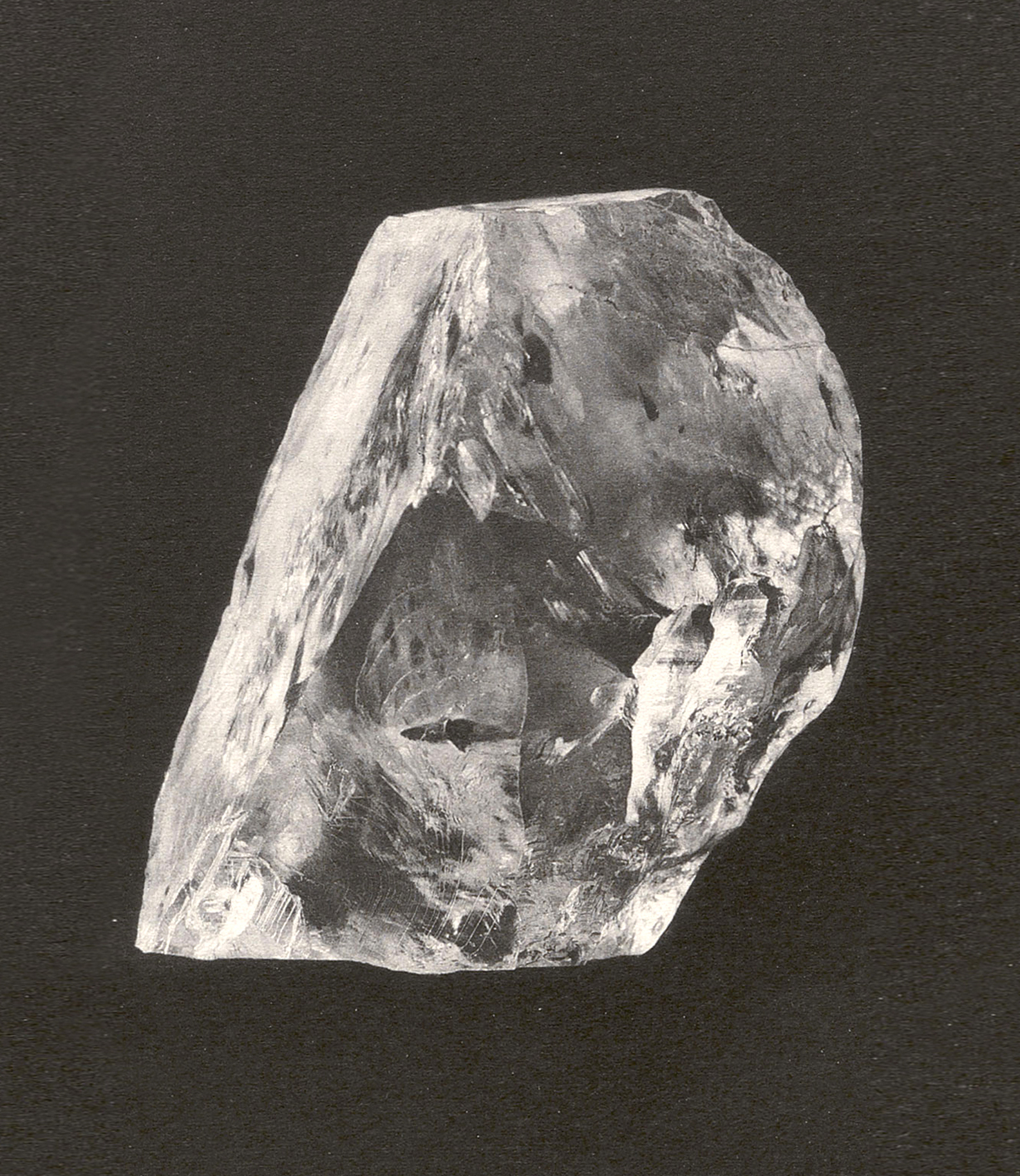

Image: Motswedi diamond, rough. Credit: Lucara Diamond

The Cullinan Diamond

3,106 carats

Discovered in 1905 in South Africa, the Cullinan Diamond is the largest gem-quality rough diamond ever found.

Image: Cullinan Diamond, rough. Credit: Royal Asscher

The Koh-I-Noor Diamond

Originated in India’s Golconda region, the Koh-i-Noor is seen as the first truly monumental diamond on record.

Advanced

X-ray technology

is displayed at the world’s largest museum, the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC, where it has captivated more than 100 million visitors, making it one of the most viewed diamonds in history.

The world’s largest diamonds form far deeper than most others,

up to 750km

below the Earth’s surface. They are almost always Type IIa, chemically pure and nitrogen‑free surface.

Karowe, Letšeng and Cullinan mines dominate the large diamond discoveries

– but why that is remains a mystery.

Image: The largest polished diamond from the Lesotho Legend: a 79.35-carat oval. Credit: © Ilan Taché Photography, photographed for Groupe Taché and Diamcad

The Hope Diamond

is displayed at the world’s largest museum, the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC, where it has captivated more than 100 million visitors, making it one of the most viewed diamonds in history.

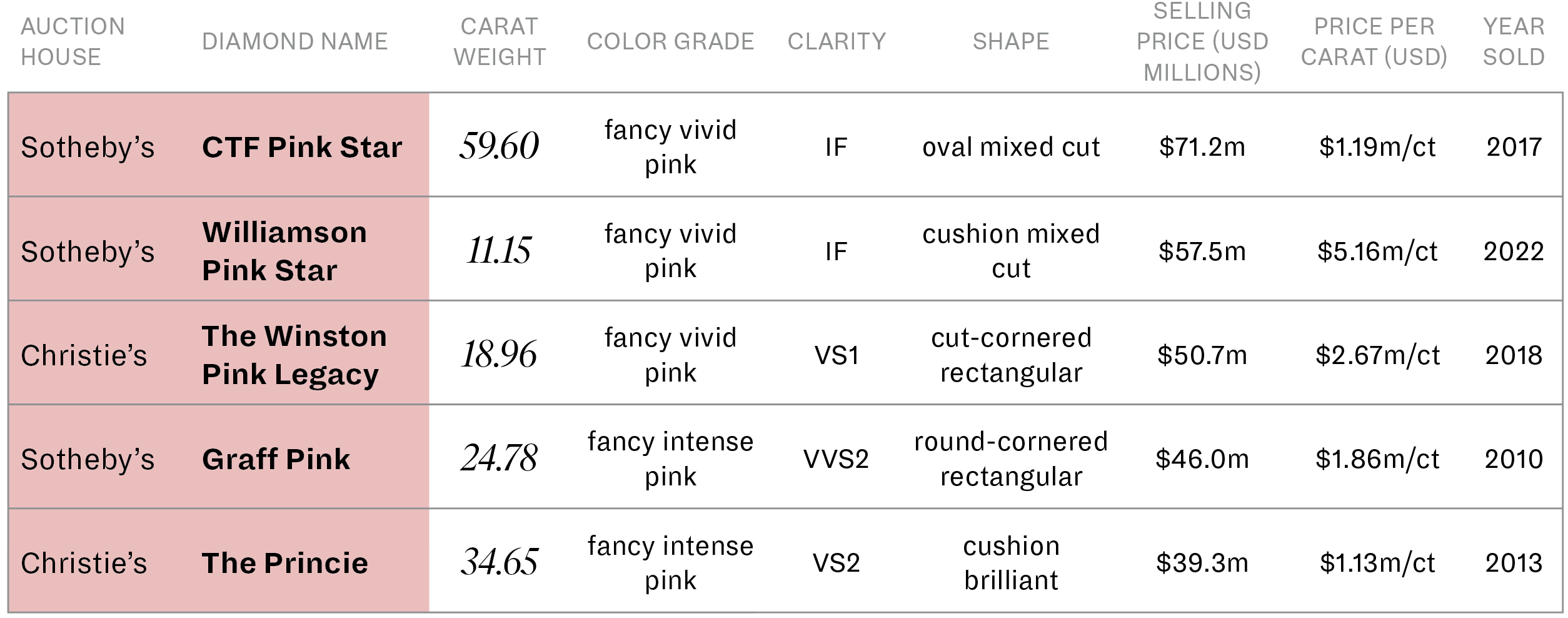

The CTF Pink Star

59.60 carats

sold at auction for $71.2 million,

making it the most expensive diamond to go under the hammer.

The Constellation

Most expensive rough ever sold:

$63.1 Million

for an 813-carat diamond.

Introduction

This report sets out to tell the story of exceptional diamonds.

While the narrative begins with historic rough discoveries, it also explores other milestones – polished diamonds that achieved landmark prices, headline-grabbing auction pieces and gems now enshrined in museum collections.

With ongoing advances in mining and recovery techniques, it seems likely that even the long-standing 3,106-carat milestone of the Cullinan will eventually be surpassed, adding a new chapter to an ever-evolving story. Remarkable diamonds have captivated people for centuries. We hope this report serves as a vivid and compelling reference for all those drawn to their enduring brilliance.

Image: Lesedi La Rona rough diamond on display. Credit: Getty Images / Spencer Platt

A Historical Overview

A historical overview of large diamond discoveries

For centuries, exceptional diamonds have stirred the public’s imagination. The bigger the rough diamond, the greater the excitement, and gem-quality giants with rare hues or great stories to tell light up the records of diamond lore.

Consider the 793-carat Koh-i-Noor from India’s Golconda region. Seen as the first truly monumental diamond on record, its origins remain shrouded in legend, yet its journey through the hands of Mughal leaders to the British Crown Jewels is well chronicled.

In the mid-17th century, the Hope Diamond was brought to France from India, where it is speculated to have been recovered from one of the Golconda mines. It is renowned less for its size than its rare blue hue. The 787.50-carat Great Mogul, also known as the Orlov, helped to make the region’s gems some of the most storied in history.

South Africa’s diamond rush of the late 1800s set new benchmarks for size and value, including the 995-carat Excelsior in 1893 and the 650.80-carat Jubilee (Reitz) in 1895, both recovered at the Jagersfontein mine near Kimberley. Those discoveries discoveries were eclipsed by the 3,106.75-carat Cullinan diamond, unearthed in 1905 near Pretoria. Its sheer size and remarkable colour stunned the world and set a record that stands today.

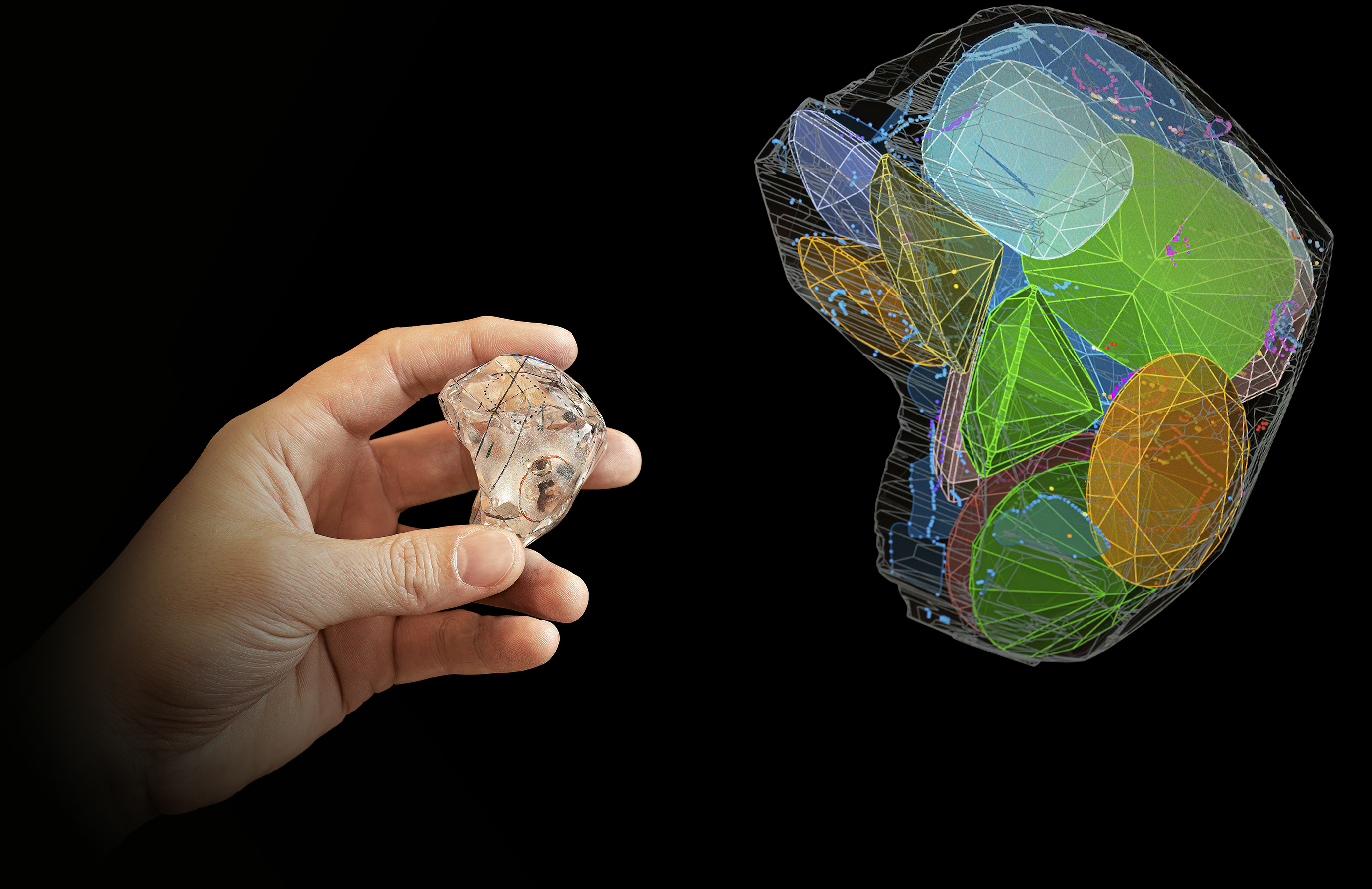

More than a century would pass before another diamond exceeding 1,000 carats was recovered, though a few came close. The deadlock was finally broken in 2015 when the 1,109.45-carat Lesedi la Rona was discovered at Botswana’s Karowe mine. The find marked a new era in the recovery of extraordinary large diamonds. Advanced x-ray technology now made it possible to detect these enormous rough gems early ensuring their preservation. In the decade since, Karowe has yielded eight additional diamonds over 1,000 carats as of November 2025, cementing the mine’s reputation as the leading source of super-sized gems.

Quality Matters

Rough diamonds come in every shape, colour and quality imaginable. Determining their value starts with a close examination of what’s possible in manufacturing – how to optimise the cutting and polishing in terms of shape, colour, clarity and size in order to yield the highest-value and most beautiful, polished diamond from the rough. The goal is to get the highest-value and most beautiful, polished diamond out of the rough.

Buyers and sellers always have that polished outcome in mind when they examine a rough diamond, and size is usually the first thing they notice.

When it comes to quality, the first assessment made is whether the diamond is industrial– or gem-quality – in other words, whether it’s fit for jewellery1, 2. But it’s not always a clear-cut distinction. Some rough are classified as near-gem, falling between the two, while others are ‘zoned’, meaning certain areas are gem-quality and the rest better suited for industrial use.

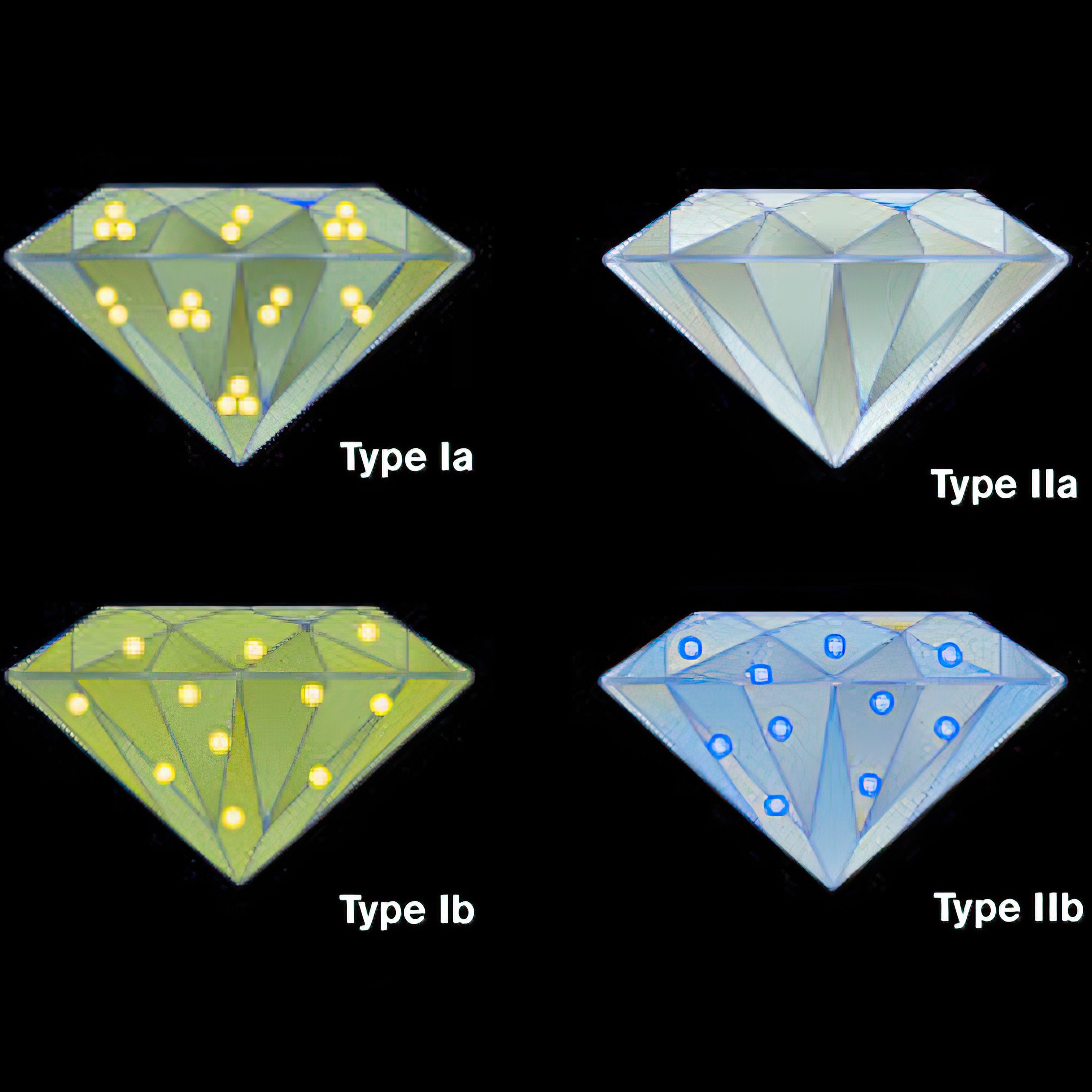

Next, they’ll assess the chemical purity of the diamond to see whether it falls into the Type I or Type II category3. Type I diamonds – accounting for the majority of diamonds recovered – contain nitrogen, which can influence their colour, while Type IIa diamonds are the rarest and most chemically pure, often prized for their brightness and transparency.

Of the 10 largest rough diamonds found to date, five are gem-quality, while only two of those rank among the top five. The super-sized industrial quality diamonds are fascinating in their own right, and many remain uncut, with some sold or donated for research or museum display.

Our focus here is on the largest gem-quality rough diamonds ever recovered. Not only are they historic for their size, but many were Type IIa and went on to become some of the most beautiful and storied polished gems ever cut.

Gemmologists use infrared spectroscopy to classify diamonds by their chemical makeup, mainly dependent on whether they contain nitrogen atoms in their crystal structure.

If nitrogen is present in measurable quantities, the diamond is Type I, which accounts for most of world production. If not, it’s Type II – much rarer and often exceptionally pure. Sub-types Ia, Ib, IIa, IIb are identified based on how those atoms are arranged or whether other elements are present. For instance, boron gives Type IIb diamonds their blue colour.

Image: Diamond Type Chart-Top to bottom: Type Ia, Type Ib, Type IIa, Type IIb. Credit: GIA, creator Peter Johnston

Top 10 Largest Gem-Quality Rough Diamonds4

RANK

NAME

CARAT WEIGHT

YEAR

COUNTRY, MINE

2

Motswedi

2,488

2024

Botswana, Karowe

4

Unnamed

1,098

2021

Botswana, Jwaneng

5

Seriti

1,094

2024

Botswana, Karowe

6

Eva Star

1,080

2023

Botswana, Karowe

10

Incomparable

890

1984

Zaire, Societé Minière de Bakwanga

Giant Gemstones of History

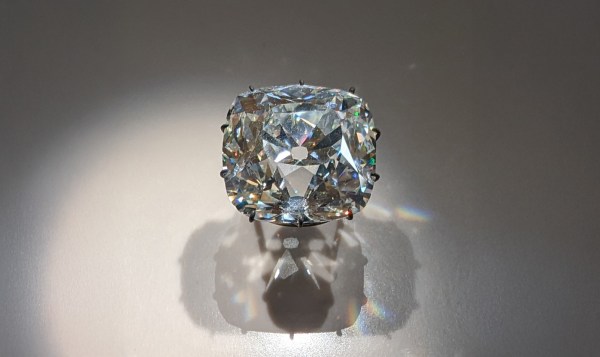

1. The Cullinan Diamond

On January 25, 1905, while inspecting an upper section of the Premier Mine (today the Cullinan Mine) near Pretoria in South Africa’s Transvaal Colony, mine manager Frederick Wells caught sight of a flash of light. It was the sun’s reflection glinting off the rock face about 18ft below the surface. Using his pocketknife, he freed a massive, glass-clear crystal and carried it to the mine office, reportedly exclaiming, “My God, look what I have found!” The 3,106-carat rough was soon confirmed as the largest gem-quality diamond ever discovered5.

News of the find spread quickly, and the press dubbed it the Cullinan Diamond, after mine owner Sir Thomas Cullinan. Amid speculation over who could afford such a gem – and at what price – the owners sent it to London for safekeeping while they searched for a buyer. Still unable to find a buyer or agree on its value, the Transvaal government purchased it in 1907 for £150,000 – an estimated $23 million in today’s terms – and presented it as a gift to King Edward VII6.

“Look what I have found”

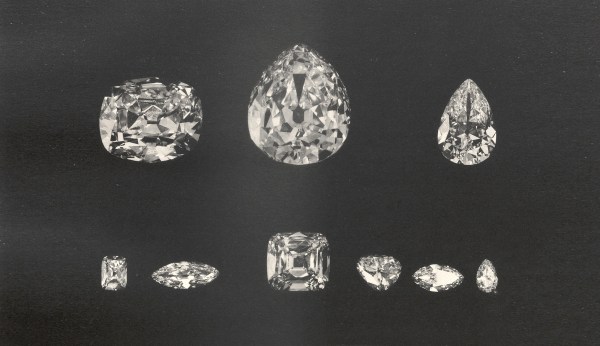

Images: Top: Cullinan Diamond, rough. Joseph Asscher makes the initial cut. The shapes and cuts of the nine major stones cut from the Cullinan diamond. Credit: Royal Asscher

At De Beers’ recommendation, the King entrusted Amsterdam’s Asscher Diamond Company (now Royal Asscher) with cutting the stone. It yielded 105 polished stones comprising nine major polished diamonds which became part of the royal collection, with two later set into the Crown Jewels7, and a further 96 minor brilliants.

Today, Cullinan I and II remain among the world’s most recognisable diamonds – admired by 3 million visitors in the Tower of London as part of the British Crown Jewels and ceremonially worn by the monarch at the annual opening of parliament and at coronations. They stand as enduring symbols of the extraordinary journey diamonds undergo: forged billions of years ago deep within the Earth, carried to the surface by volcanic forces, noticed by chance in a glint of sunlight, and transformed through human craftsmanship into the very embodiment of royal grandeur for more than a century.

Image: Coronation portrait of Queen Elizabeth II holding the Cullinan sceptre and the Cullinan crown. Photographer: Cecil Beaton. Collection: Royal Collection

2. Motswedi Diamond

Wellspring of Wonder

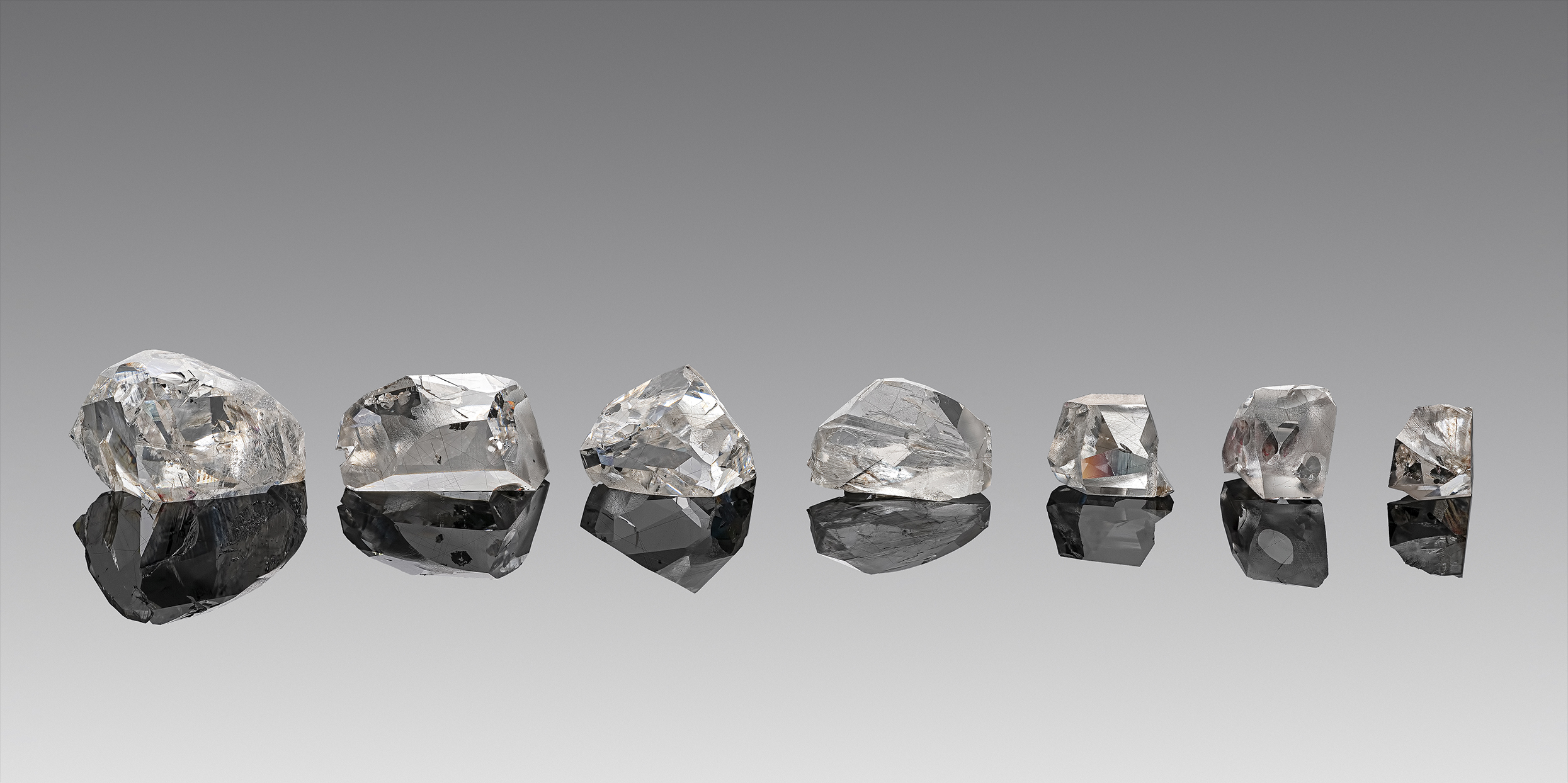

After the Lesedi La Rona broke the 1,000-carat barrier (see next page), Botswana’s Karowe mine led the charge to the next milestone of this millennium. That moment came in August 2024, when the mine yielded an extraordinary 2,488-carat diamond8 – reaffirming Karowe’s reputation for producing some of the world’s most remarkable gems.

Following a public naming competition, the rough was named Motswedi9 – meaning ‘water spring’ in the local Setswana language, or more fully, ‘the flow of underground water that emerges to the surface, offering life and vitality.’ It’s an apt homage to the mine that continues to be a wellspring of extraordinary stones.

Analysis by the Gemological Institute of America (GIA)10 confirmed Motswedi as a single Type IIa crystal with no detectable nitrogen, and suggested it likely formed far deeper within the Earth than most diamonds. This made its sheer size and purity even more exceptional.

As of publication, Motswedi remains in its rough form.

Motswedi Diamond, rough. Credit: Lucara Diamond

Motswedi Diamond, rough. Credit: Lucara Diamond

This is undoubtedly a diamond of great historical importance. I have never seen a gem-quality diamond of nearly this size.

Tom Moses,

GIA’s Executive Vice President and Chief Laboratory and Research Officer.100 million visitors, making it one of the most viewed diamonds in history.

The 2,000-Carat Club

One other diamond exceeding 2,000 carats has been recovered from Karowe. In July 2025, the mine yielded a 2,036-carat stone11, its second largest to date and the fourth largest diamond in history. However, the rough has been classified as near-gem and described as light brown in colour, rather than the gem-quality standard that would qualify it for inclusion among the aforementioned greats.

3. Lesedi La Rona Diamond

Our Light – “God, it’s a Diamond!”

A decade has passed since Tiroyaone Mathaba’s fateful moment in the sorting room at Botswana’s Karowe mine. Then a 27-year-old trainee sorter, he noticed a tennis ball-sized gem which he soon realised was no ordinary find.

“At first I wanted to scream,” he recalled. “Then I whispered, ‘God, it’s a diamond! It’s a diamond, it’s a big diamond!12”

Weighing 1,109.45 carats, the discovery was the first diamond to break the 1,000-carat mark since the Cullinan in 190513. After a nationwide naming competition with 11,000 entries, it was fittingly called Lesedi La Rona – “Our Light” in Setswana14.

Lesedi La Rona was sold in 2017 to Laurence Graff for $53 million. Under Graff’s meticulous care, an 18-month cutting and polishing journey transformed the rough into an exquisite 67-piece collection, headlined by The Graff Lesedi La Rona15.

At 302.37 carats, the square emerald-cut, D-colour, flawless diamond is the largest of its shape and quality ever graded by the GIA, Graff claims. The remaining 66 satellite stones range from under a carat to more than 26 carats, each inscribed “Graff, Lesedi La Rona” to mark their shared origin.

Lesedi La Rona Diamond, polished CREDIT: Graff

My love affair with diamonds is life-long and crafting the Graff Lesedi La Rona has been an honour. […] Cutting a diamond of this size is an art form, the ultimate art of sculpture. It is the riskiest form of art because you can never add and you can never cover up a mistake, you can only take away. You have to be careful and you have to be perfect.

Laurence Graff

Chairman of Graff

The Larger Light

GIA researchers believe the Lesedi La Rona may once have been twice its final size. Their study suggests the 1,109-carat Lesedi La Rona, the 812-carat Constellation, and three other colourless diamonds weighing 374, 296, and 183 carats – all recovered from Karowe around the same time – likely originated from a single massive rough. Using advanced spectroscopic and imaging techniques, the GIA team found “compelling evidence” that the five stones shared comparable growth histories, indicating a common origin with a combined weight of at least 2,774 carats16.

The significance of the recovery of a gem quality stone larger than 1,000 carats, the largest for more than a century cannot be overstated.

William Lamb

CEO, Lucara Diamond

Geological Factors

The power of origin

Diamonds are survivors. Those that reach the Earth’s surface have endured a journey spanning millions – even billions – of years. Formed deep within the mantle, mostly at depths of 150 to 200km below the surface they are carried upward by rare and violent volcanic eruptions – the most rapid known to man. As the magma cools, it crystallises into volcanic rocks known as kimberlite or lamproite, which serve as the diamond’s delivery system to the surface. It’s a testament to the resilience of diamonds that they can survive such an intense ascent as the magma has the capacity to dissolve the diamond – and an even greater wonder when stones of exceptional size make it all the way intact.17

What large diamonds teach us about the Earth

The world’s biggest diamonds offer unique insight into the hidden secrets of the earth’s deepest interior. Research first published in 2016 by GIA in the journal Science and then a second publication came in 2017 in the journal Gems & Gemology, showed that record-size stones like the Cullinan, Lesotho Promise, and other large Type IIa diamonds belong to a distinct group, which form far deeper than ordinary gems – between 360 and 750 kilometres beneath the surface, in the Earth’s mantle transition zone.18

These so-called ‘CLIPPIR’ diamonds are named for their shared traits: ‘Cullinan-like’, ‘large’, ‘inclusion-poor’, ‘pure’, ‘irregular’, and ‘resorbed’. The GIA researchers found that they contain microscopic traces of iron and nickel, surrounded by methane and hydrogen. That means these giant gems were born in liquid metal rather than silicate magma, which helps explain their exceptional size, purity, and lack of nitrogen.

That discovery changes what we know (because this is going back almost 10 years to 2017) about the Earth’s interior, as we cannot directly sample these great depths in our planet. Each of these diamonds carries clues about how carbon, oxygen, and other elements cycle through the planet’s interior, offering a rare glimpse into the deep processes that have shaped the Earth for billions of years.

Oppenheimer Diamond Collection # 6513. Diamond in kimberlite matrix, 52.45 ct. Sir Oppenheimer Student Collection. Credit: GIA, photographer Robert Weldon.

Rivers of Diamonds

Not all diamonds are found where they arrived at the Earth’s surface. After a kimberlite or lamproite volcanic eruption, erosion breaks down the host rock and releases diamonds that may be carried by rivers far from their source. Over millions of years, these stones may travel many hundreds of kilometres before settling in riverbeds, beaches or ancient gravel layers, forming what are known as alluvial deposits.19, 20

The journey acts as a natural filter as fragile and flawed crystals are broken or worn away, leaving behind tougher, higher-quality – though typically smaller – gems. That’s why alluvial deposits in places such as Namibia, Angola, Sierra Leone, and the Golconda region have yielded beautiful, gem-quality stones, yet rarely the giants seen in primary kimberlite sources such as Botswana’s Karowe or South Africa’s Cullinan mines. Diamonds extracted directly from the volcanic ore, by contrast, have not been subjected to the traumas of transport over millions of years and across thousands of miles.

Below the Surface

The mines behind the masterpieces

The Technology Game Changer

The past decade has seen an unprecedented run of spectacular diamond discoveries, largely thanks to advances in mining and recovery technology.

Chief among these innovations is X-ray transmission (XRT), which allows miners to spot diamonds hidden within recovered ore by measuring differences in density. Diamonds absorb X-rays differently from ordinary minerals, meaning sensors can detect them as the ore travels along a conveyor belt. A short burst of air then neatly separates the diamond-bearing rock from the rest21.

In essence, the technology empowers miners to spot large diamonds before the ore reaches the crushing circuit, preventing them from being broken up.

Lucara Diamond Corp. was among the first to implement XRT technology for primary recovery, installing it at the Karowe mine in 201522. The investment paid dividends later that year when the mine yielded the 1,109-carat Lesedi La Rona – the first diamond over 1,000 carats discovered in more than a century. Building on that success, Lucara in 2017 installed four more XRT units to process finer size fractions and added a mega diamond recovery (MDR) circuit to protect and extract even larger stones23, 24.

Gem Diamonds commissioned a pilot XRT unit at its Letšeng mine as early as 2011 and fully commissioned the system in 2017. Known for its exceptionally high-quality large rough, Gem Diamonds has credited the technology with improving recovery efficiency and reducing damage to Letšeng’s most valuable diamonds.25

Since then, other producers have adopted similar systems at their operations, including at the Cullinan, Ekati, and Lulo mines – each renowned for their production of unique, high-value diamonds.

Karowe

Calm kimberlite, colossal diamonds

Karowe – meaning ‘precious stone’ in Setswana – couldn’t be more aptly named. Owned and operated by Lucara Diamond Corp., the Botswana mine has earned near-legendary status since production began in 2012 for its steady stream of spectacular, large, high-quality diamonds.26

Its secret lies in the AK6 kimberlite pipe. The pipe consists of three lobes – North, Centre and South – each with distinct characteristics, but it’s the South Lobe that stands out for its rich content of Type IIa diamonds.27

Calm kimberlite, colossal diamonds

Karowe has yielded nine diamonds larger than 1,000 carats, including two over 2,000 carats.

Letšeng

A wondrous wetland

Perched in the Maluti Mountains of the Kingdom of Lesotho in Africa, Letšeng – meaning ‘the wetland’ in Sesotho – is the world’s highest diamond mine, sitting at an altitude of about 3,100 metres (10,000 feet). It is co-owned by Gem Diamonds (70%) and the Government of Lesotho (30%)28, 29.

Famous Letšeng Diamonds30

• Lesotho Promise (2006) – 603 carats; sold for $12.4 million to Laurence Graff, cut into 26 D-colour flawless stones.

• Graff Lesotho Pink (2019) – 13.32 carats rough; sold for $8.75 million ($656,934 per carat), polished into a 5.63-carat, fancy vivid purplish pink gem.

The Collaboration Era of Exceptional Diamonds

Increasingly, companies are teaming up with luxury jewellery houses to transform exceptional rough into polished diamonds that anchor high-end collections. The Lesotho Legend is a prime example. Recovered at the Letšeng mine, the 910-carat rough was sold to a partnership between Groupe Taché and Samir Gems, who worked with Van Cleef & Arpels to develop its Legend of Diamonds collection. The 25-piece suite featured 67 diamonds, all cut and polished from the same rough by Antwerp-based master cutters Diamcad31, 32.

Credit © Ilan Taché Photography, photographed for Groupe Taché and Diamcad

Cullinan

Big, blue, deep & old

Few diamond mines carry the historic weight of Cullinan. Discovered in 1902 and famed for producing the record-breaking 3,106-carat Cullinan Diamond, it has yielded more than 750 stones over 100 carats and remains one of the world’s most known sources of rare Type IIb diamonds, coloured by trace amounts of boron.

Geologically, Cullinan is unique; its Premier kimberlite pipe is one of the deepest ever mined, with current operations extending to about 730 metres below surface33, 34. Expansion work at the mine, operated by Petra Diamonds, is now targeting depths of more than 1,100 metres. It is also one of the oldest deposits. The volcanic event that transported the diamonds to the surface occurred approximately one billion years ago, meaning that the gems have to predate the eruption, implying that the Cullinan Type IIb diamonds are at least a billion years old, although none have been dated.

Into the Deep35

The De Beers Blue diamond is an internally flawless exceptionally rare fancy vivid blue 15.10-carat stone. Analysis by the GIA of the De Beers Blue showed high boron content and an undistorted crystal structure. Research* has demonstrated that their boron derived from the Earth’s crust sinking to extreme depths of up to 750km, where a very rare population of diamonds can form. The gemological characteristics of the De Beers Cullinan Blue suggest it is one of these superdeep diamonds.

De Beers Blue Credit: Sothebys

Golconda

The cradle of great diamonds

Golconda diamonds, found in ancient alluvial deposits along the Krishna River valley in south-central India, are revered as the world’s first and most storied source of diamonds. The earliest documentation of these is from the fourth century BC.

Unlike diamonds that have been found since the 19th century in kimberlites, Golconda diamonds were carried to the surface by kimberlites and redistributed across the surface by erosion over millions of years. This natural selection, combined with their formation deep within the Earth’s mantle under extreme conditions, produced diamonds of extraordinary structural perfection. Many of the best known historic diamonds from the region are Type IIa, containing almost no nitrogen impurities, a rarity that gives them their legendary limpidity, soft brilliance and near-colourless ‘liquid light’ appearance36, 37.

The precise kimberlite source of the Golconda production has never been found. Geologists believe the source lay within India’s ancient Eastern Dharwar Craton, where the original kimberlite pipes have long since eroded, deepening the geological mystery behind their allure. These factors, together with their royal provenance, make Golconda diamonds synonymous with purity and prestige. Many of the world’s most celebrated gems – including the Koh-i-Noor, Hope, Regent, Great Mogul and Dresden Green – originated in these riverbeds35, 36.

Icons of Crown & Kremlin

The Koh-i-Noor,37, 38 believed to have weighed 793 carats in its rough form, and the Great Mogul39 – thought to have been around 787 carats – still rank among the largest diamonds ever recorded. Today, the Koh-i-Noor, polished to 105.6 carats, forms part of the British Crown Jewels, while the Great Mogul is widely believed to have been recut into the 189.6-carat Orlov Diamond, which now resides in the Diamond Fund of the Moscow Kremlin.

The Crown of Queen Mary of England, in the front, The Koh-I-Noor diamond. Credit: Getty Images / ullstein bild Dtl.

Cutting the Titans

Carving a royal legacy

The Cullinan wasn’t the first super-sized diamond the Asscher Diamond Company cut and polished. The Amsterdam-based firm, run by five Asscher brothers, had already built its reputation on the Excelsior. At 995.20 carats, it was the largest rough gem-quality diamond ever discovered before the Cullinan.40, 41, 42

Even so, the 3,106-carat Cullinan demanded a far deeper level of analysis. Its sheer scale was one factor, but the ownership of the stone and the intense public attention surrounding it raised the stakes even further.

On the recommendation of De Beers, King Edward VII invited the Asschers to assess the diamond. Two of the brothers – company head Abraham and master cleaver Joseph – travelled to Buckingham Palace to view the stone and make a proposal, which the king accepted.

The first challenge was simply getting the diamond from London to the Asscher workshop in Amsterdam. Newspapers were told it would travel in a sealed box aboard a British Navy destroyer, a bit of deliberate misdirection. In truth, Abraham slipped the Cullinan into one pocket of his jacket, kept a gun in the other, and quietly boarded a regular passenger ship. That’s according to his grandson Edward Asscher, veteran diamantaire and former CEO of Royal Asscher, the modern successor to the family business, which is today managed by his children Lita and Mike.

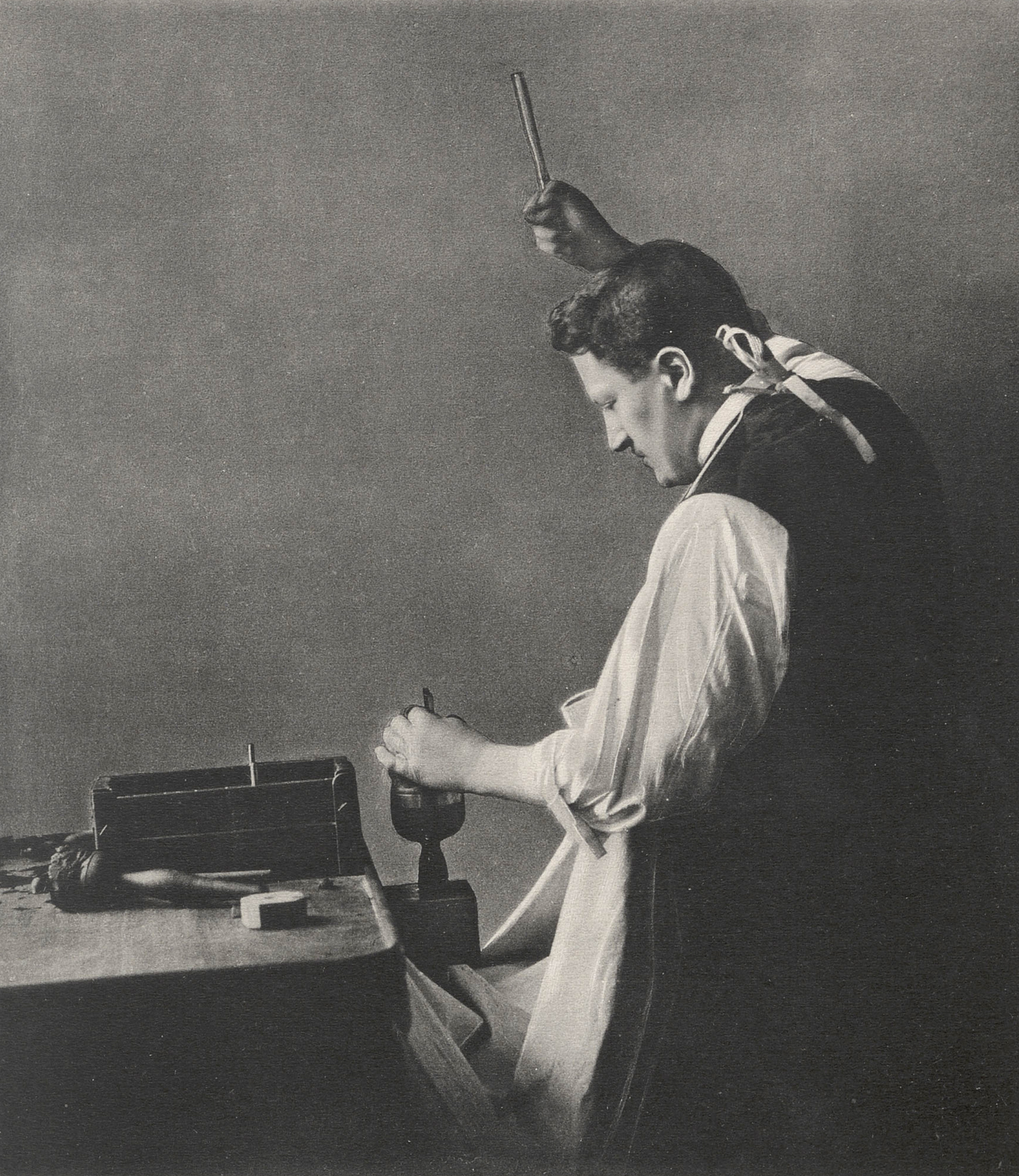

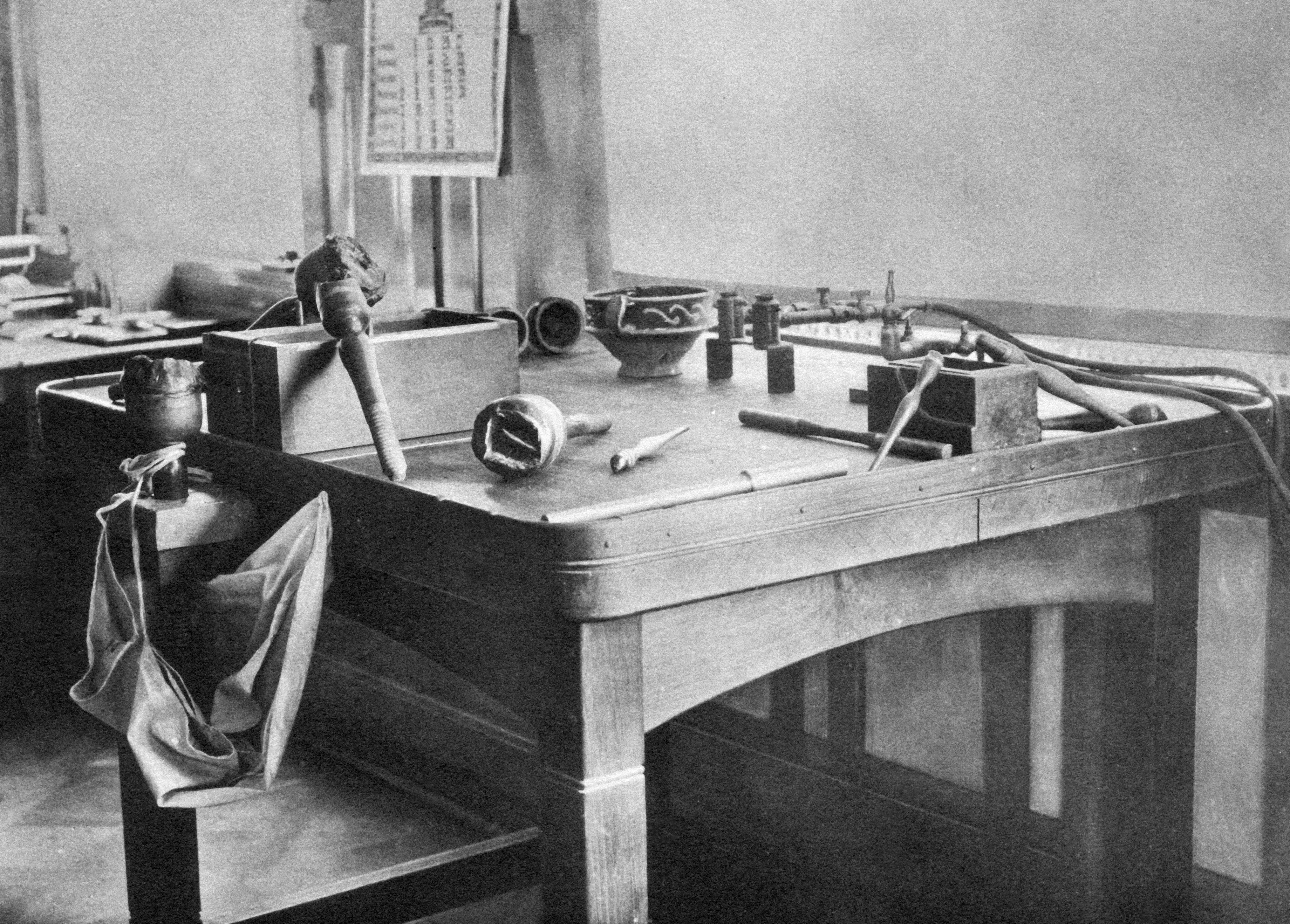

Image: Joseph Asscher cutting table. Credit: Royal Asscher

Cleaving the Cullinan

With the Cullinan safely in Amsterdam, the brothers spent months studying it. Their assessment made it clear they would need to cleave the Cullinan, splitting it into two parts. In practice, they had to execute two cleavages. Near its centre, the rough stone held several black inclusions that had to be removed, and the planned layout of additional smaller stones required a structure that would allow for consistent, workable polishing.

Meanwhile, Joseph Asscher had custom tools made that he believed were essential for cleaving a diamond of the Cullinan’s size. Once they were ready, he set to work, spending the next month carving a precise incision roughly one centimetre deep. By early February 1908, he was finally prepared to attempt the cut of the largest gem-quality rough diamond ever found.

The cleaving became a public spectacle. The room filled with family members, journalists and a representative of the king, all waiting to witness the moment. The drama came quickly. When Joseph finally delivered the blow, the diamond held firm while the knife blade snapped instead.

He cleared the room, then deepened the incision in the stone, and the adjustments worked. When he attempted the split again, the diamond cleaved cleanly, this time with only a small group present, including the King’s representative.

A persistent legend claims Joseph fainted after the first attempt, though the family has always dismissed it. In fact, after successfully cleaving the stone exactly as calculated, he invited everyone back in for a champagne celebration. Maybe he fainted after the party, the family likes to joke.

Royal destiny

The Asscher team spent the next two years polishing the Cullinan, largely because of the sheer number of stones it yielded. They ultimately presented the crown with nine major polished diamonds destined for the Royal Collection, along with another 96 smaller stones. Little is known about those smaller stones today.

The nine larger diamonds are the ones that cemented the Cullinan’s legacy, and they remain embedded in British royal tradition and folklore.

The largest of the gems, Cullinan I, known as the Great Star of Africa, remains the biggest colourless polished diamond on record at 530.20 carats. It is graded D colour and potentially flawless. Cut into a pear shape with 74 facets, it sits at the heart of the Sovereign’s Sceptre with Cross, the signature piece of the British Crown Jewels. Its sister stone, Cullinan II, the Second Star of Africa, is a 317.40-carat cushion cut, also D colour and potentially flawless, positioned prominently at the front of the Imperial State Crown43, 44.

Cullinan Diamonds original box with tools. Credit: Royal Asscher

The Cullinan III and IV Brooch (C) and Cullinan VII Delhi Durbar Necklace. Credit: Getty Images / Samir Hussein

A brooch that bridged monarchs or A brooch that bridges monarchs45, 46

Among the many standout jewels in her collection, Queen Elizabeth II reserved a particular brooch for her most significant appearances. Set with the Cullinan III, a 94.4-carat pear shape, and the Cullinan IV, a 63.6-carat square cut, the piece accompanied her during her Diamond Jubilee in 2012.

After her passing, the diamonds reappeared in Queen Camilla’s coronation crown, as they had in the same crown worn by Queen Mary at her coronation in 1911. Outside of such moments, the crown uses replicas of the Cullinan III, IV, and V so the originals can continue to circulate as brooches.

For the Asscher family, the most meaningful moment came in 1958, when Queen Elizabeth wore the brooch during her state visit to the Netherlands. She visited the Asscher offices, where the Cullinan had been cut and polished, and met Louis Asscher, the last surviving of the five brothers.

During that meeting she told him, “Here, Mr. Asscher, you can take them in your hands. You held them in your hands before.” Despite his failing eyesight, Louis recognised the stones instantly and was deeply moved by the gesture.

Creating the Centenary

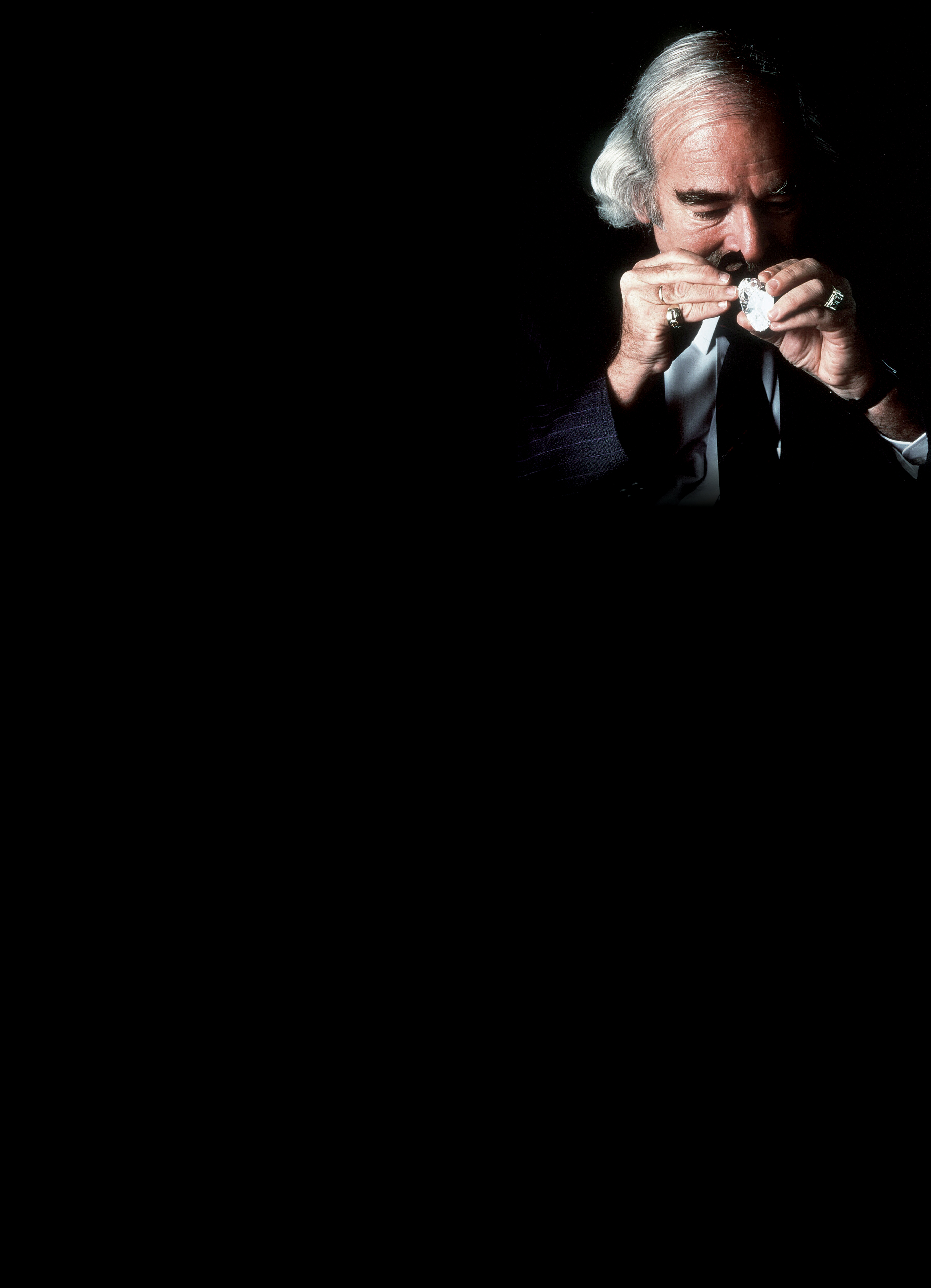

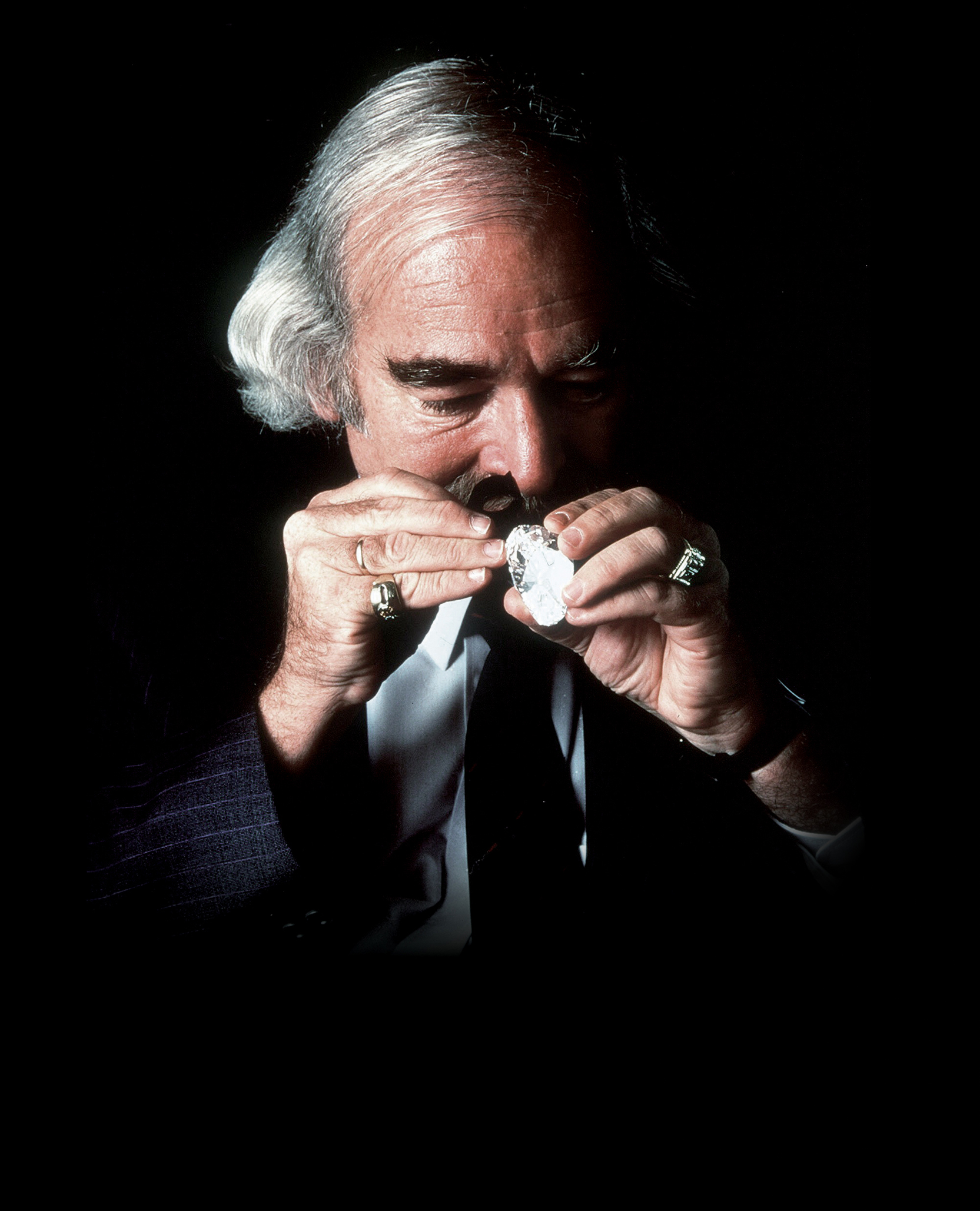

Beyond its perfect colour and exceptional purity, the Centenary Diamond – as it was ultimately named – seemed to possess an almost spiritual presence.47, 48 Master cutter Gabi Tolkowsky recalled his first encounter when he was invited to appraise it:

“I met the diamond in London in a box. I didn’t touch it because I hadn’t seen such a thing before in my life. And then when I took it in my hands, it married my hand, it just was part of myself because it gave me so many thoughts that I changed as a person,” he recalled in the documentary Treasures of the Earth – Diamond Passions.

Tolkowsky was commissioned to lead a small, secretive team working in a specially constructed underground cutting facility at De Beers’ research laboratory in Johannesburg, built to allow him absolute focus on the task at hand.

He spent nearly two years studying the diamond – planning, mapping, and learning every nuance of its structure. After considering several models, the team chose a design that would prioritise brilliance over weight retention.

Another year of cutting and polishing followed. When the work was complete, in February 1991, the result was a 273.85-carat, D-colour, flawless, modified heart-shaped brilliant with 247 facets.

De Beers hailed the Centenary Diamond one of the most perfectly cut stones ever produced, unveiling it in May 1991 as the climax of its 100-year celebrations, which began in 1988.

The diamond was later loaned to the Tower of London, where it was displayed for several years. De Beers is believed to have since sold it to an unnamed private owner.

I will never forget how I worked on the Centenary for 154 working days – an entire working year – carving and carving away with my bare hands. I removed more than 50 carats before we started polishing.

Gabi Tolkowsky

Master cutter

Image: Gaby Tolkowsky and Centenary Diamond

Modern tech, timeless craft

If the Cullinan were found today, it would almost certainly be cut into a very different set of polished gems. Diamond manufacturing has evolved dramatically over the past century and, more sharply, in the last decade, as technology allows far more efficient analysis and optimisation of rough, especially large specials where the value stakes are higher.

Two major developments pushed cutting and polishing into a new era, notes Bart De Hantsetters, Managing Director of Diamcad49, which specialises in manufacturing top-quality, high-value diamonds. The first was the advent of laser technology, which brought a significant jump in precision for cutting, sawing, shaping and marking. The tools existed earlier, but they became mainstream and widely used in the 1980s50.

The second big shift came with the rollout of scanning technology in the early 2000s. Suddenly manufacturers could build a digital twin of the rough and map out a far more considered cutting and polishing plan. Typically, the scan is used to determine the optimal combination of polished stones, identifying the largest feasible round, cushion or pear from the rough and then assessing how the remaining material can be most effectively used.

Diamcad, which has polished some of the most famous diamonds of recent years, including the Lesedi La Rona, the Lesotho Legend, the Lulo Pink, the Peace Diamond, and the Queen of the Kalahari, approaches it differently.

The company developed its own software that simultaneously considers all the decision variables of the planning process, rather than building cutting plans sequentially. That shift allows it to identify the highest-value options and then combine the force of its algorithms with its human expertise to reach the best possible outcome for each diamond.

Diamond cutting is still very much an art, despite the technological progress, particularly with these exceptional stones, De Hantsetters stresses. That extends well beyond planning and into the actual cutting and polishing.

“These polished diamonds have a perfection about them because we have about 20 polishers working on them day in and day out, guided by master cutters pushing them to reach that level of perfection,” he says.

Eli Huygelberghs, Diamcad’s Chief Operating Officer, agrees.“When you’re working on a gem with that kind of intimacy over a long stretch of time, it becomes a part of you,” he says. “The diamond becomes part of the family.”

The Lesotho Legend, Before and After Polishing

After the first split, the larger half was laser-cut into seven more pieces, ranging from 25.93 to 217.47 carats. Credit: © Ilan Taché Photography, photographed for Groupe Taché and Diamcad

It was a very moving and unprecedented experience for me holding this incredible diamond and trying to discover its secrets. It truly was a treasure surrounded by mystery that had yet to be unlocked.

Jean–Jacques Taché

Managing Director Sales at Taché Diamonds

Legend of diamonds is the fruit of over four years of reflection, creation and intense emotions inspired by the beauty of stones and virtuoso savoir-faire.

Nicolas Bos

CEO of Richemont

Image: The 67 D-colour, flawless Lesotho Legend diamonds became a 25-piece Mystery Set High Jewellery ensemble by Van Cleef & Arpels. Credit: © Ilan Taché Photography, photograhed for Groupe Taché and Diamcad

The Legacy Setters

Museum Pieces

Every diamond is unique, but some possess qualities so exceptional they transcend value and deepen their mystique. Their significance isn’t always measured by price; a select few, like the legacy jewels preserved in royal collections and museum displays, are beyond appraisal. They’re priceless for their rare blend of provenance and beauty.

This section highlights some of the remarkable gems that have truly left their mark, beyond those already featured in this report.

The Hope Diamond

The Hope Diamond51 ranks among the most mysterious and storied gems in history. Believed to have originated in India’s Kollur mine, it passed through French and British royal hands, earning a reputation for bringing misfortune to its owners. Originally part of the French Blue52– a 67-carat diamond owned by King Louis XIV – the diamond was stolen during the French Revolution in 1792 and later recut into its present form.

It resurfaced in London in the early 19th century, where it was acquired by banker and gem collector Henry Philip Hope, after whom it is named. Over the next century, it passed through several notable owners, including American socialite Evalyn Walsh McLean, before being purchased by jeweller Harry Winston, who donated it to the Smithsonian in 1958.

Graded by the GIA53 as a 45.52-carat fancy dark greyish blue diamond of VS1 clarity with very good polish and symmetry, the Hope Diamond has captivated more than 100 million visitors since its arrival at the Smithsonian, making it one of the most viewed and celebrated diamonds in history.

The Hope Diamond. Credit: Chip Clark, Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History (digitally modified by SquareMoose)

The Regent Diamond

The Regent Diamond CREDIT: Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication

The Regent Diamond, a 140-carat diamond of almost unreal perfection, is considered one of the most symmetrical old-cut diamonds in history – a remarkable feat for a stone cut and polished in the early 1700s54. Its exceptional clarity, described as perfectly transparent, and its ‘first water’ white brilliance has earned it an almost mythical reputation for centuries.

Discovered in 1698 in the legendary Golconda mines in India, the rough stone weighed nearly 410 carats before being transformed into a sumptuous 140.64-carat cushion-cut diamond, with an estimated colour of D or E and perfect or near-perfect clarity – one of the most accomplished masterpieces of old-cut diamond cutting.

Acquired by Philippe d’Orléans, then Regent of France, the diamond became one of the most cherished jewels of the French sovereigns. It successively adorned the crown of Louis XV, then that of Louis XVI, before shining on the sword of Napoleon Bonaparte55, embodying through each reign the continuity of a sovereign light.

In 1887, when the French Crown Jewels were sold, the Regent was miraculously preserved and incorporated into the national collections. Today, it remains in the Louvre Museum.

Constellation Diamond. Credit: Lucara Diamond

Constellations Align

The Priciest Rough on Record

A day after announcing the recovery of the Lesedi La Rona, Lucara Diamond Corporation unveiled two more remarkable rough gems from the Karowe mine in Botswana56. They weigh 374 carats and 812.77 carats respectively57, were later believed to have been fragments, along with the Lesedi La Rona, of a much larger diamond that was broken apart in their journey to the Earth’s surface58.

Still, they were worthy of attention in their own right, even as the Lesedi grabbed most of the headlines. That changed in May 2016, when the 812.77-carat stone was sold to Dubai-based Nemesis International for $63.1 million. Christened the Constellation, its $77,649-per-carat price tag makes it the most expensive rough diamond ever sold.

The Brightest Star

The Most Expensive Polished

The CTF Pink Star ranks as the most expensive diamond ever sold at auction. It was originally known as the Steinmetz Pink, later the Pink Star, and briefly The Pink Dream. The oval-shape, 59.60-carat, fancy vivid pink, internally flawless59 diamond drew intense global interest – especially from the fast-growing Asian market – when it returned to auction at Sotheby’s Hong Kong in April 2017.

After a competitive bidding war, the hammer fell at $71.2 million, with the winning bid submitted by Chow Tai Fook chairman Henry Cheng Kar-Shun, who renamed the gem in tribute to the Hong Kong-based jeweller and its founder60.

It wasn’t the first time the diamond had come to auction. In fact, it sold for an even higher price – $83 million – at Sotheby’s Geneva in 2013. However, the buyers defaulted on payment, forcing the auction house to take back the stone61 and hold it in inventory for the next four years.

The CTF Pink Star’s story traces back to 1999, when De Beers unearthed a 132.5-carat rough diamond in Botswana. While the company has never publicly confirmed which mine produced the stone, it was most likely recovered from either the Damtshaa or Jwaneng mine, both renowned for yielding exceptional Type IIa and fancy-colour diamonds. Diamond manufacturer Steinmetz – now known as Diacore – spent nearly two years cutting and polishing the gem before unveiling the spectacular finished stone in 200362.

CTF Pink Star. Credit: Chow Tai Fook

Under the Gavel: Icons of the Auction Room

The Priciest Pinks

The CTF Pink Star may hold the record as the most expensive diamond ever sold at auction, but the Williamson Pink Star – named in tribute to both the CTF Pink Star and Tanzania’s Williamson mine, where it was found – topped it in relative value, fetching $5.1 million per carat at Sotheby’s in 2022.63

The Winston Pink Legacy. Credit: Christie’s

Williamson Pink Star. Credit: Sotheby’s

Breathtaking Blues

Coincidence or fate, both De Beers Blue and the Oppenheimer Blue sold for $57.5 million, tying as the most expensive blue diamonds ever auctioned. While the Oppenheimer Blue edges out The De Beers Blue in value per carat, The Blue Moon of Josephine holds the top spot by that measure.64

The Oppenheimer Blue. Credit: Christie’s

The Blue Moon of Josephine. Credit: Sotheby’s

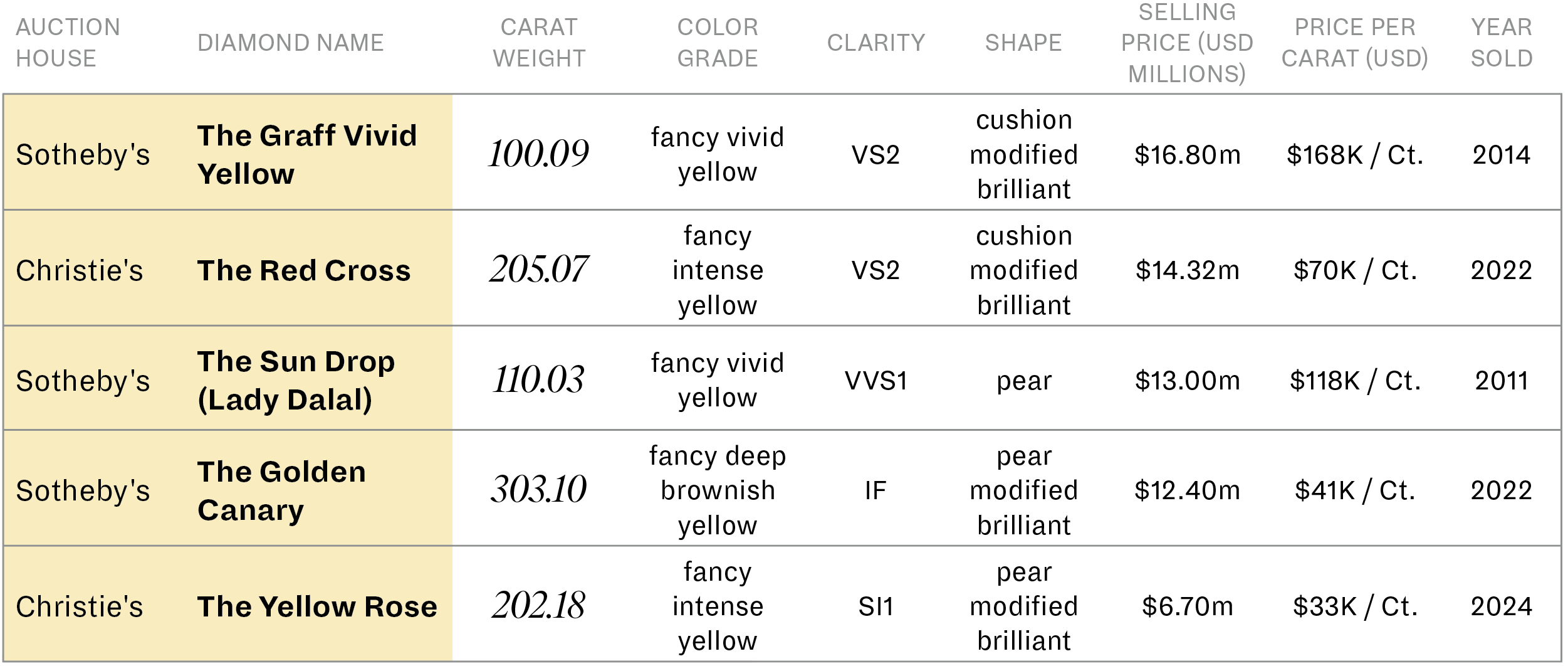

Notable Yellows

According to Sotheby’s, the largest yellow diamond ever to appear at auction was The Golden Canary, cut and polished from The Incomparable – a 890-carat rough diamond recovered in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.65, 66

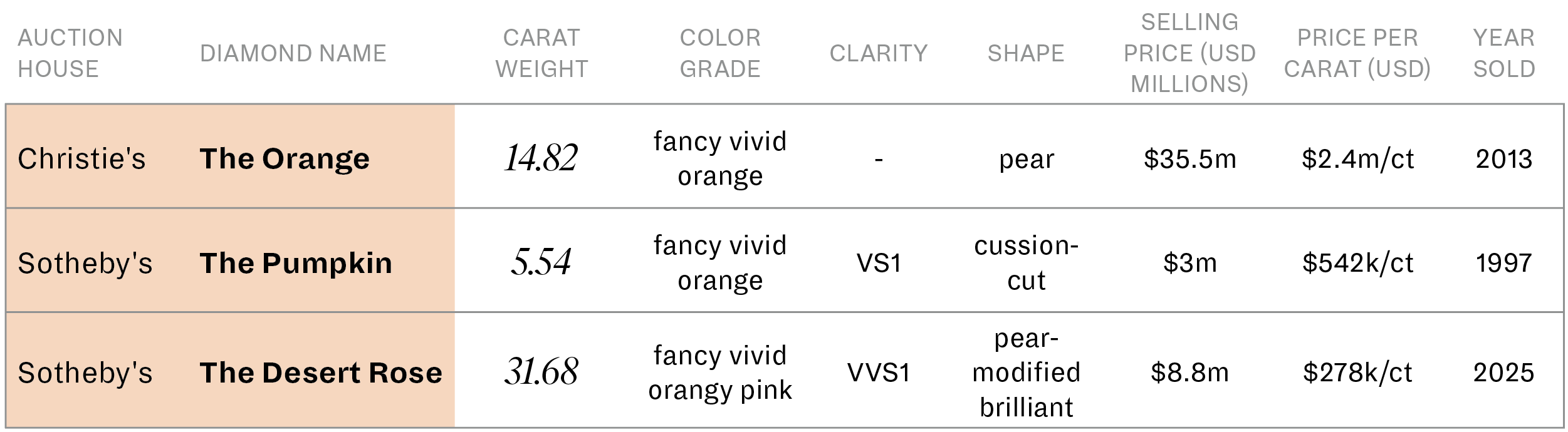

Orange Trailblazer

For years, the Pumpkin Diamond, auctioned by Sotheby’s on Halloween Eve 1997 held the title of the world’s largest fancy vivid orange diamond. But in 2013, a 14.82-carat pear-shaped gem known simply as The Orange set the auction world ablaze when Christie’s unveiled it as the largest fancy vivid orange diamond on record. It sold for CHF 32.6 million (equivalent to $35.5 million at the time).67

The Desert Rose, a 31.68-carat, pear-modified brilliant, the largest fancy vivid orangy pink diamond, VVS1 clarity, sold for $8.8 million at Sotheby’s inaugural Abu Dhabi Collectors’ Week in December 2025. Five bidders competed for the stone, which set a new auction record for a fancy orangy pink diamond.68

The Orange. Credit: Christie’s

The Desert Rose. Credit: Sotheby’s

Download This Report

Natural Diamond Council’s Diamond Report series covers trends, origin, and other particularities of the ultimate gemstone – natural diamonds. Created in collaboration with governments, communities, and experts, these reports empower consumers, media, and industry professionals with transparent insights and engaging facts.

Many thanks to the following contributors:

Avi Krawitz

Ray Ferraris

Diamcad

Edward Asscher And The Royal Asscher

Ilan Taché And Groupe Taché

De Beers Group

Lucara Botswana

Gemological Institute Of America (GIA)

Graff

Richemont

Chow Tai Fook

Sotheby’s

Christie’s

Smithsonian’s National Museum Of Natural History

Jackie Steinitz

SOURCES

1. USGS, Industrial Diamond Statistics and Information

2. Industrial Diamonds – Thermo Fisher Scientific

3. GIA, Digging into Diamond Types (2014)

4. QTS Kristal Dinamika (Ray Ferarris) – Largest Rough Diamonds – A List

5. GIA, Historical Reading List: The Cullinan Diamond (2020)

6. Phillida Brooke Simons (Fernwood Press), Cullinan Diamonds | Dreams & Discoveries (2001)

7. Royal Collection Trust, the Cullinan Diamond

8. Lucara Diamond, Lucara recovers epic 2,492 carat diamond from Karowe Mine

9. Lucara Diamond, Lucara names Epic 2,488 Carat and 1,094 Carat Diamonds

10. GIA, GIA Examines the World’s Second Largest Diamond

11. Lucara Diamond, Lucara announces Q2 2025 results

12. Rapaport, Lesedi La Rona Finally Sees the Light

13. Lucara Diamond, Lucara Makes Diamond History; Recovers 1,111 Carat Diamond

14. Lucara Diamond, Lucara Names 1,111 Carat Diamond Lesedi La Rona

15. Graff, Introducing The Graff Lesedi La Rona

16. GIA, Diamond Geology | Modern Advances in the Understanding of Diamond Formation

17. GIA, Kimberlites: Earth’s Diamond Delivery System (2019)

18. GIA, The Very Deep Origin of the World’s Biggest Diamonds (2017)

19. GIA, Recent Advances in Understanding the Geology of Diamonds (2013)

20. GIA, Diamond Sources and Production: Past, Present, and Future (1993)

21. Tomra, Tomra’s promise to diamond mining operations: 98% diamond recovery guaranteed (2020)

22. Lucara, Lucara Reports Strong Q2 Performance And Updates On The Plant Optimization Project (2015):

23. Lucara, Lucara Announces Completion of its Diamond Recovery Capital Projects (2017)

24. Crown Publications, XRT technology ushers in a new era in diamond recovery (2017)

25. Tomra, Tomra’s XRT technology – a game-changer at Letšeng Diamond Mine in Lesotho

26. Lucara, Karowe Mine Summary

27. Lucara, Karowe Diamond Mine 2023 Feasibility Study Technical Report (2024)

28. Gem Diamonds, Mining | Operational Review:

29. GIA, Letšeng Unique Diamond Proposition (2015)

30. Gem Diamonds, Our Famous Diamonds

31. Van Cleef & Arpels, The Lesotho Legend, an exceptional rough diamond:

32. Interview with Diamcad

36. Sotheby’s, Discover Type IIa Diamonds – The Most Exceptional 10-Carat Diamonds (2025)

37. GIA, Historical Reading List – The Koh-i-noor Diamond (2018)

40. Interviews with Edward Asscher

41. Royal Asscher, The Cullinan (2021)

43. Royal Asscher, The Cullinan (2021)

45. Interviews with Edward Asscher

46. In Style, All About Queen Elizabeth’s Most Valuable Brooch, Cut from the World’s Largest Diamond

47. EMS Films via YouTube, Diamond Passions Gabi Tolkowsky (1999)

48. Jeweller Magazine: A moment with Sir Gabriel Tolkowsky, ‘the father of modern brilliance’ (2021)

49. Interview with Bart De Hantsetters

50. GIA, Modern Diamond Cutting And Polishing (1997)

51. Smithsonian, History of the Hope Diamond

53. GIA: Grading The Hope Diamond (1989)

54. International Gem Society, The Regent Diamond: Jewel of Empires and Revolutions (2025)

55. Louvre, Sun, Gold and Diamonds

58. GIA, Diamond Geology | Modern Advances in the Understanding of Diamond Formation

59. Sotheby’s, The Pink Star – One of the World’s Great Natural Treasures

60. Sotheby’s, Record Diamond is the Star of Hong Kong

61. Reuters, Sotheby’s acquires “Pink Star” diamond after buyer defaults (2014)

62. Diacore Partners in Pink Star 59.60 Carat Fancy Vivid Pink Diamond

63. The Diamond Press based on Sotheby’s, The Five Most Expensive Pink Diamonds (2025)

and Christies, 10 history-making pink diamonds offered at Christie’s (2023)

64. The Diamond Press based on Sotheby’s, Discover the 6 Most Expensive Blue Diamonds, and Christie, The Oppenheimer Blue, and Christie’s, Bleu Royal

65. The Diamond Press based on Sotheby’s, The Four Most Expensive Yellow Diamonds Over 100 Carats, and Christie’s, Magnificent Jewels Led by Two 200 Carat Diamonds,

and Christie’s, Magnificent Jewels Auction Led by 202 Carat Yellow Diamond

66. Sotheby’s, Sotheby’s Showcase – The Golden Canary (2022)

67. Christie’s, The Largest Fancy Vivid Orange Diamond in the World

68. RAPAPORT – Pink Diamond Smashes High Estimate at Sotheby’s in Abu Dhabi,